ruba abu-nimah: You grew up in Queens. Where did you study photography?

kr: First, in high school. I was a bad student. I went to a few different schools. I started getting really into it when I was 17 or 18.

ran: You clearly love it and have a very sophisticated knowledge of the medium.

kr: I think that was my first sense of being creative within something that was considered art. When I was a kid, we’d go to the MOMA and see these pieces of really high art. I had friends who could draw really well. Photography let me exercise my creativity. When I was in college there was this group of kids who all went to some art high school. They just knew about stuff—it was crazy. I think that exposure is really important.

ran: Did you have any idea what you wanted to do?

kr: I didn’t, and I was never pushed one way or another towards a career.

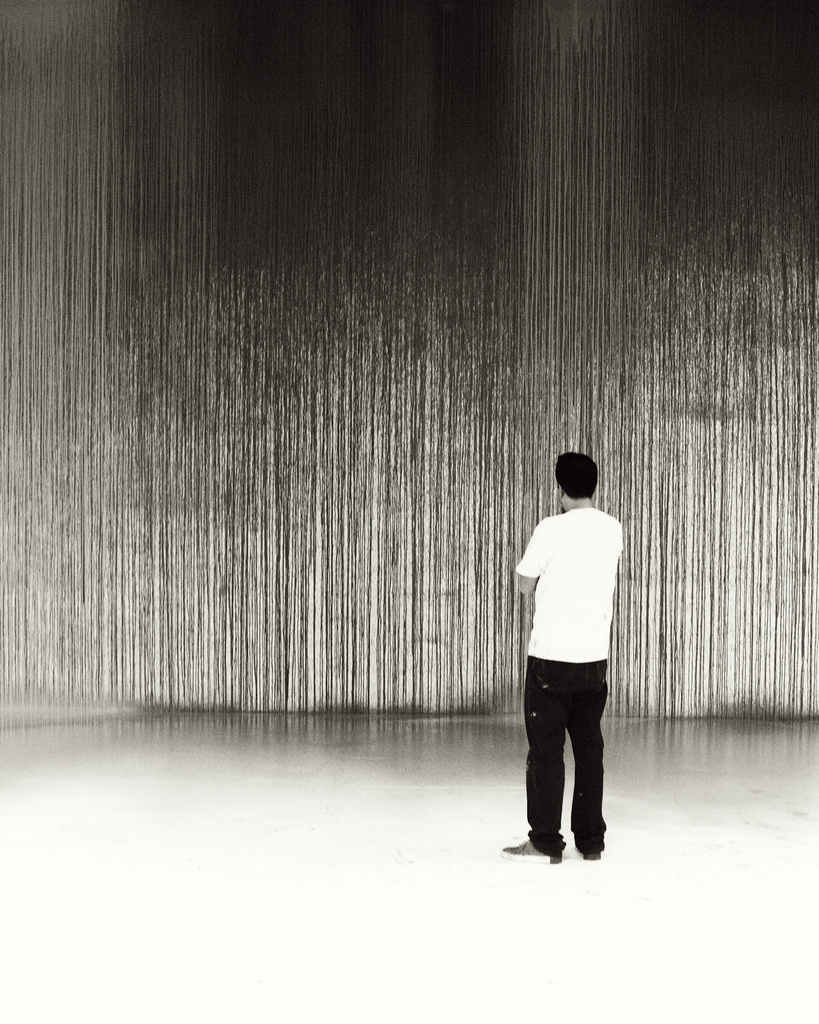

ran: How did you go from being interested in photography and the arts to writing on walls?

kr: There was no pivotal moment. I grew up in New York and wrote graffiti. When I was younger, when I was a teenager, everyone had a name or knew someone who wrote. Graffiti was very much a part of our youth. Some people took it really seriously. Others just dabbled. I wasn’t a real graffiti writer. I was a skater, but then I broke my knee and got more into graffiti at 17.

Krink Bottles. Photo: Bjorn Iooss

ran: What about the risk?

kr: Nobody cared about the risk at our age. I skated in the ’80s, so it was like acid drops and bonelesses and stuff like that. We would jump off ten-foot or twelve-foot drops on a skateboard and land them—now that’s a risk. It was intimidating at first but we didn’t really think about the risk.

ran: You were just like: “I’m going to keep doing this. It’s fun.”

kr: Yep. We were having fun. There’s also an obsessive quality to it. When I was a kid, I think I didn’t have that drive to go to college. I was a little misguided.

ran: Tell me about California. When did you go to San Francisco?

kr: From ’92 until ’98. When I graduated from High School, there was this expectation that I should go to college. I went to Boston to the Museum School of Fine Arts. I hated Boston. It was a total nightmare. The people and the attitudes were so conservative. I went there when I was 18. I used to go to Hardcore Matinees and things like that. In Boston, the shows were 21 or over; we couldn’t even go. We couldn’t even buy beer. We used to go to clubs at 16! I guess I was so naïve but I finally went to this place where they didn’t allow any of that, it was just kind of mind-blowing. I didn’t grow up like that. For us, it was a non-issue. We’d be cool with the local Hindu dude who sold us beer at the store on the corner. Boston was just fucked up like that. On top of that there were all of these like jock dudes who would pick fights with me. I don’t know if I just looked too alternative or something. So I dropped out freshman year and went home. I would go out until four in the morning. My mom would ask me, “Where the fuck have you been?” I grew up in a pretty strict household, but I had already had my taste of independence. So I saved some money and moved to San Francisco. I didn’t go for school. I just went. I got a job at a one-hour photo spot and did that for a year. It was really nice in a way because I was doing my own thing but eventually I began to ask myself what the hell I was doing. That’s when I decided to go back to school.

Early Krink bottle. Photo: Henry Leutwyler

Mailbox Drip on Bleecker Street. Photo: KR

ran: Where?

kr: San Francisco Art Institute is where I studied photography. My program was very open-ended, though. You could really bring anything in. The school wasn’t a technical school; it was a fine arts school. The department where I was, it was the most open. It was more about ideas. I learned a lot there, though if you looked at my grade point average you wouldn’t think I learned anything. Art school was weird. I was always in the library, and I went out and looked at art in San Francisco. I found that sometimes in a class of twenty people, I’d be the only one who looked at the shows. I don’t know what that means about everyone else.

ran: You’re still very active. You go to all of the shows and galleries. You know what’s going on.

kr: I go and I look. I’m not so much interested in the scene, but contemporary art is definitely a major influence. I think it was always shocking how my classmates didn’t look at the art. I like art school, and I like all the art students. I live near Pratt. I see the freshman. They’re awesome. They make their own clothes. New York City is different. If you’re from some small town, you must feel like an alien and a weirdo when you get here. Kids from New York, especially Manhattan—they’re super sophisticated. Even in Queens, it’s just very different from the rest of the country. They’re multicultural.

ran: Yes, I think they’re very much the culmination of their environment. And you’ve also spoken about the kids Downtown. It’s very strange because it’s a whole group of people who are all doing similar things who are all drawn to each other.

kr: It also changes so much. Downtown, there’s a great creative community constantly being pushed around because of rent. I used to live in the Lower East Side and I can barely stand to be in that neighborhood. It’s a very different place today—it’s crazy. The kids are all down in Chinatown now.

KR tag on Centre St. Photo: KR

ran: Why do you think people like Krink it? I mean, you can get ink anywhere.

kr: Sort of. But there was a point when you couldn’t get ink anywhere. Back in the day it was very, very limited as to what you could get. You’ve got to understand, if you want to take it all the way back, there were just stationary stores and art stores. No Staples. No Office Depot. The inks you could get were mostly pilot ink, which is used in markers. It was a super limited supply. You couldn’t just buy it the way you can today.

ran: How did you make it?

kr: I basically stole all the raw materials. I made my own. From there, I harnessed my aesthetic and style in the street, which you might just call marketing. I was marketing my personal style. And what I was doing within this culture. Eventually, that style was bottled and sold to the public. Before that you just could not find ink like that. It just didn’t exist.

ran: So was it a conscious decision then?

kr: It became a conscious decision because with other projects, things fell through. I would ride these highs and lows. It was difficult for me. It’s still difficult for me, to be honest. With Krink, it was one step removed. It was a brand. It was a product. I could focus on dishing that out in order to pay my bills. I was getting older. I needed to make a living. I had to make a major sacrifice mentally to pursue this business and leave fine art. And then it took off.

ran: Do you think you settled?

kr: I don’t know. What’s happening today is that I still have this weird scratch. Krink has been amazing. I love everything that we’ve done as a team. It’s been super exciting but I’m also interested in doing more big projects. When I made the decision to focus on Krink, it grew exponentially. I was able to channel my energy. The brand fills a side of me. I went to school and studied genres and stuff like that. Krink and the branding—it satisfies that part of my interests. I have a friend who I went to school with. He’s very successful. For him, it’s the same. We can apply our art school and contemporary art interests into these grand applications.

ran: Graphic design is an art. I think it’s an undervalued art. Graphic design and branding go hand in hand.

kr: I think branding and graphic design are different things. I didn’t study brand or graphic design. There was not one computer. I learned how to do things on the computer from friends, looking over their shoulders or on the phone. I asked questions. I’m still no expert.

It’s more about that attitude, that spirit in how you make things. The tool, the ink—those become part of the whole process.

ran: You’ve made and maintained a strict direction for your brand. But it doesn’t seem like it was done consciously, was it?

kr: No, nothing is done consciously. It’s crazy. The only thing we consciously do is pay our bills on time. When it comes to branding, they’re all decisions based on what we think is cool or what we think is right. We get approached by agencies. Sometimes, they talk to us like: “What are you even saying? What the fuck does that mean?” I can’t stand it. They say these things and I just can’t relate to them at all. What we do is small and organic.

ran: It’s very small, but very coveted. For a kid in a skate park, a Krink marker is as coveted as a Chanel bag for a woman living on the Upper East Side. You’ve created something aspirational. Would you ever sell Krink?

kr: I don’t know. First of all, we’re so small. Companies that buy other companies usually buy ones that are much bigger than mine. I think a partnership could be interesting. Some people don’t understand that in the world of business there are more and more of these gigantic conglomerates. They don’t just own all of the products. They own the distribution, the raw materials, the molds. They’ll shut you out if you try to make something. This is happening more and more in the US. It’s the same thing in fashion. You go to Duty-Free and it’s all owned by LVMH.

ran: LVMH and Estee Lauder. They have the power to control the positioning of the brands on the floor in those stores, too.

kr: These companies are able to shut out the small brands. Our company, we pay fair wages. We support the local economy. We’re into all of that. But that all drives the price up. In the grand scheme, at least in the US, it’s all chains and big box.

ran: It’s odd for New Yorkers, because we don’t see as many of those stores here.

kr: I drove cross country and it blew my mind. People who fight over brands and talk shit, they don’t realize that the same company owns everything.

HVW8 Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brandon Shigeta

ran: They also don’t realize that across their brands, they use the same formulas.

kr: I’d like to be more accessible, though. I love Chanel, but I don’t want Krink to be like the $3,000 bag. I wish my products could be cheaper and that we can still pay fair wages to everyone.

ran: Does your fine art work inspire you in creating the products?

kr: It’s a mix. Take the fire extinguishers. They’re something I’ve used. I’ve repurposed an existing material and made it available to the public.

ran: Did you ever imagine in your wildest dreams that a fire extinguisher could become an art piece that people would covet?

kr: The repurposing of these things into creative tools—it’s the same as having a photo of Warhol’s brush. Warhol didn’t make the brush. I make the brush and I’m using it. It’s just part of the process, and the history of my method. The extinguisher is the same as the marker at Krink. It’s that same spirit of looking to your environment and finding your tools. I came from an era where you found your own paint and tools. Maybe you only had a few pairs of gloves, but you coveted them. You took care of them. You brought them home and immediately soaked them in thinner and cleaned them out. You couldn’t buy them. You could only find them in small numbers. If you’re climbing to a rooftop you only use as much as you can carry with as much time as the spot will allow you. It’s more about that attitude, that spirit in how you make things. The tool, the ink—those become part of the whole process.

Museum of Image and Sound, Sao Paolo.

Some people link Krink to fashion. They link it to desirable items. They can also link it to mass destruction.

ran: Why do you think people are so interested in your output?

kr: I’ve been very fortunate that people are interested in the things I’ve done. Some people link Krink to fashion. They link it to desirable items. They can also link it to mass destruction. I thought it was very interesting when a friend came in here and suggested that we make the caps blue and put stickers in particular places. They were both great ideas, but they came specifically from his experience with fashion design. When I say that I just do this intuitively, it’s not like I worked for five years and I understand these intricate things about package design.

ran: So where do the decisions come from?

kr: It’s more that they’re based in practicality, economy, taste and design sensibility. There’s literally no background in design to inform the design that I’ve pushed forward. I feel like I’m part of a creative culture in Downtown New York City. Fashion and design and all the things that come with that, from t-shirts at Supreme to Bobbie Brown makeup. My specific category of products is not in any of those worlds. Not everyone wants a marker, but many people think the brand is great and that generates a creative community around our product.

ran: Do you ever think about changing it up?

kr: At this age, we all make sacrifices, right? I have a lot of friends who struggle as artists and they are full-time. They do not do anything else. I run a business. If I were to step away from this, it would go down before it went up again. I’m getting older. Stability and paying my rent are important. I love New York and I don’t want to bad mouth it, but it can definitely be a trap.■