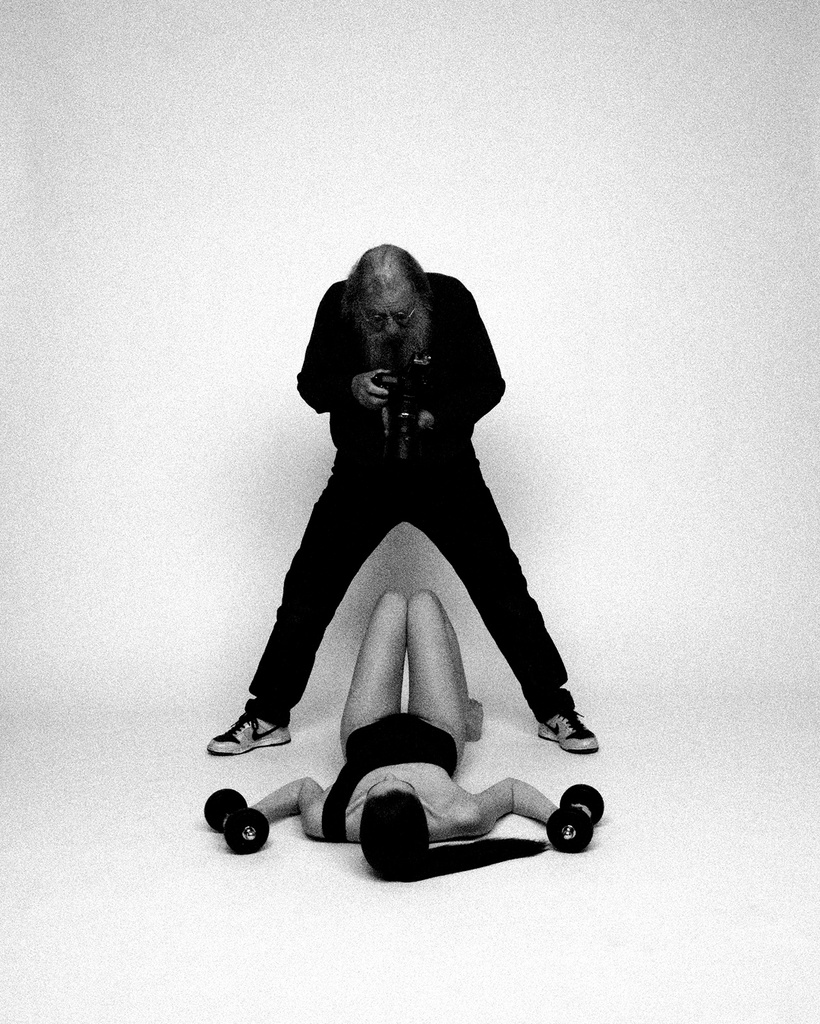

thomas schwab: On my way to your place, I ran into a friend. When I told him I was en route to interview you, he got really excited. “Ask him about his relationship with the models on his sets. He is the master of erotic photographs! To me, he’s like the ancestor of Terry Richardson.” I actually don’t think of you in that way. I associate you more with Tom Wesselmann, Allen Jones and other sensual pop artists.

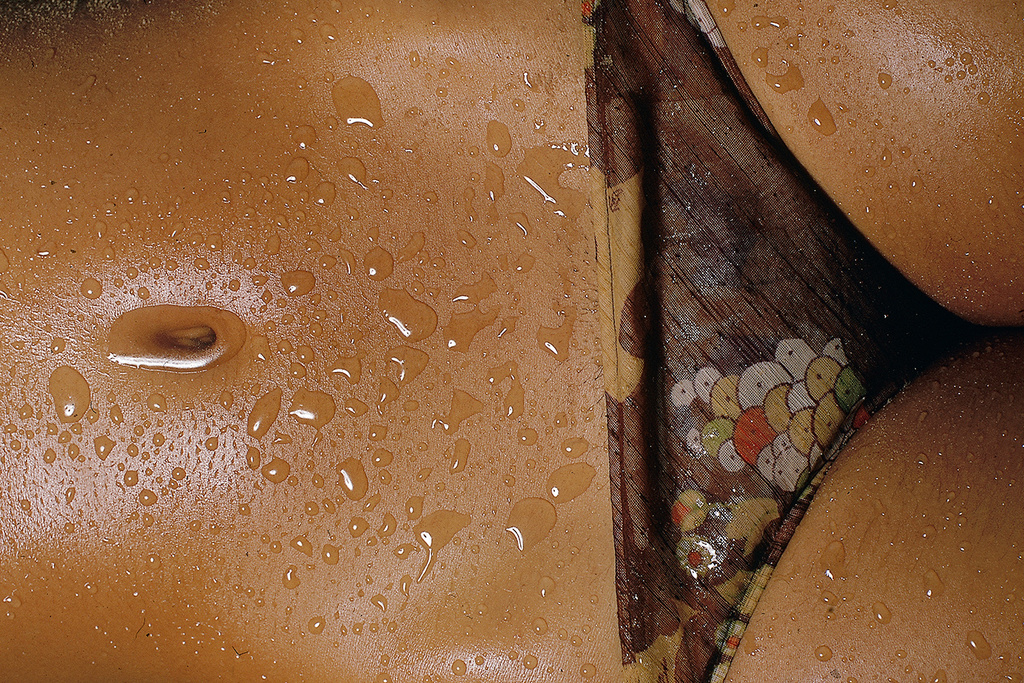

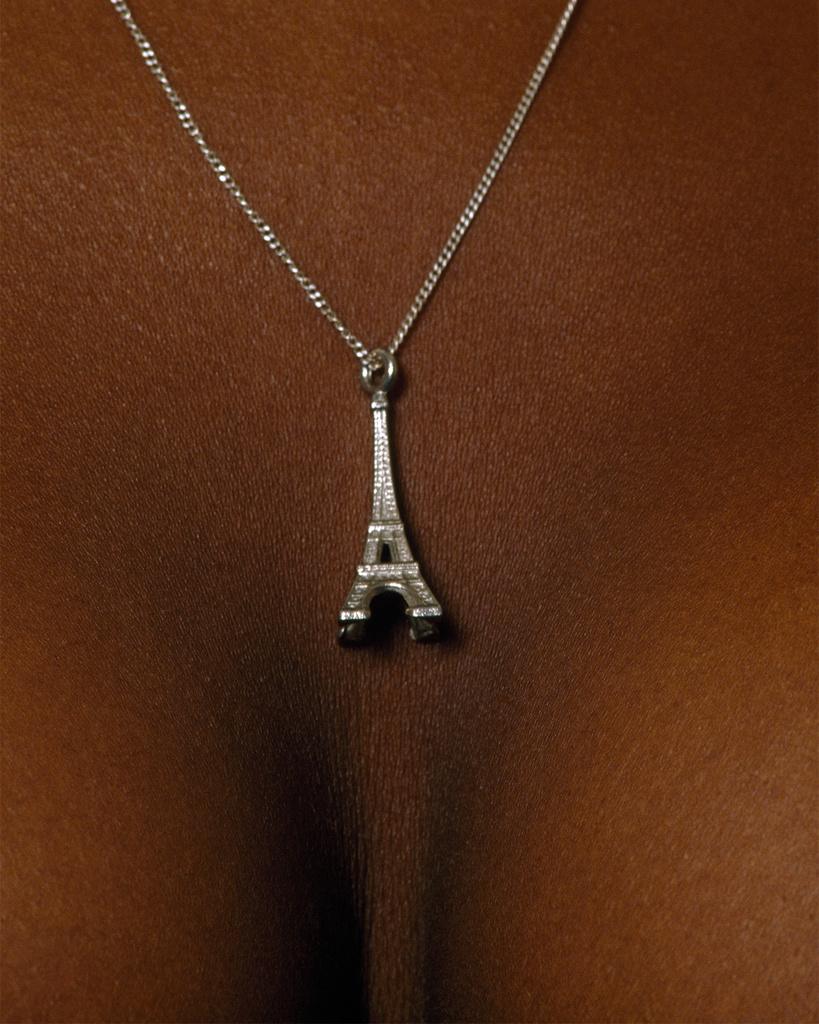

harri peccinotti: (Laughs) Yeah, I suppose. I don’t consider myself a so-called erotic photographer. I take pictures of girls with no clothes on because I like them with no clothes on. I just like the look of them. I think of it more in a painterly way. I’m never thinking in a vulgar way when I’m taking those pictures.

ts: Have you ever been considered a pornographic photographer?

hp: Well, I hope not! “My father, the pornographic photographer,” my son always says. He’s joking because he knows I’m not.

ts: Have you taken “sexy” photographs from the beginning? It feels like you’ve always had your set style.

hp: Only a small amount of the photography that I’ve done is sexy. They’re the ones that people remember, though, so maybe they’re the more successful ones. Or maybe other people are more interested in it than I am. I didn’t start with a goal to take sexy pictures, or not-sexy pictures. I just like women, really—women of all sorts.

ts: I see you as having particularly two styles of photography. Some are really graphically oriented. And others could be called more “lifestyle.” Which style do you prefer?

hp: I think graphically when I take pictures. That’s probably why they look that way. I’ve sort of been brought up in graphic design. But in terms of preferences, I don’t have a preference. All of the pictures that I do, I do with the same stupidity. Even if I’m doing a landscape, I take it the same as if I was doing a pair of lips, a dress, a picture in a bar, anything. I can’t analyze it, but I’m always doing the same thing. I just do it. If it looks spontaneous, I’m still being reasonably graphic when I’m looking through the lens.

ts: I think so, too. And I’ve never seen you bored. It seems like you still enjoy taking pictures.

hp: Oh, yeah, I do, absolutely. I probably don’t have the same stamina at times. I like to be instantaneous, but still be graphic. You know, try to get the shape, the point in the frame.

ts: Do you consider yourself more like an art director, a photographer or an image maker?

hp: I always think of myself as an art director, as that’s how I started. But on the other hand, I’m a photographer. I think that they’re all connected—all those things—like music, graphic design, photography and filmmaking. If you’re interested in one, normally you’re interested in all of them. It sometimes is very difficult if you want to do everything. But in fact, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t. You need to be a part of all of them to be good at any of them.

ts: To me, it’s more like a vision that you can apply to anything.

hp: I think like that. But I know some people don’t. There are people who are one-track-minded. If you take someone with a real style, though, like Jean Loup Sieff or Art Kane, where you can recognize their pictures wherever you see them—those artists are always still interested in everything else. They don’t necessarily do it all, but they have a well-rounded knowledge. Unlike politicians, who don’t seem to know anything about anything. (Laughs) But if you’re in the creative business, you need to be a part of that wider conversation.

I don’t consider myself a so-called erotic photographer. I take pictures of girls with no clothes on because I like them with no clothes on.

ts: That’s funny what you’re saying about people who are interested in other things. When you look at William Klein, Jean-Paul Goude, Peter Knapp, etc., there is a lot of humor in the photographs. It is done seriously—but it is never serious…

hp: There has to be some humor or some comment in it. Not always, but very often you can make a comment even if you’re doing some really straight thing. Lots of people don’t notice it, but it can be there, just jokingly. Like the picture I did of a girl eating a sandwich with green nails, and lipstick all over the cigarette. I used to always see girls in cafés eating and smoking cigarettes at the same time. Lipstick was coming off on their food. I thought, “That’s crazy! That’s really fashionable!” So I did the picture, and it’s a comment. In the ‘60s and ‘70s, it was really a fashionable thing—people stubbing cigarettes out on their plate. They’d push the plate to one side and it looked absolutely disgusting. I was brought up not do those sorts of things. Now, of course, vulgarity is virtually a part of some photographers’ styles. Mine was more of a comment.

ts: Your pictures do not age at all—even the ones from 40 years ago. Did you always take pictures?

hp: I left school when I was fourteen and went to work in the graphic design part of a factory that made Smith’s Motor Accessories. They built clocks for dashboards, sparking plugs and the first radios to fit into cars. I was learning to do technical illustrating and things like that. That was my training. We were forced to learn how to do roughs. Drawings that were coarse, but good enough to show a client. They depicted what and how we intended to do something. Part of the process was taking photographs. They had a little room with a Rolleiflex in it and some lights. So from the very start, I was taught to use that in a studio. We did all sorts of pictures there. They used to have a class at the factory, once a week, for people interested in painting. There were no so-called art directors.

ts: When did that change?

hp: Graphic design existed because of Bauhaus and things like that. Fashionable art directors came in the late ‘50s and early ‘60s. Before that, you were a commercial artist—just another kind of craftsman. If they wanted a bit of type, you drew it. If you had an idea, you had to draw it on the page and show someone. That’s almost how I became a professional photographer. I used to do the photographs for the ads. I would take the still life or something, for my rough. After I commissioned it, the client would say, “We prefer the original one you did.” So, I might as well have done the whole thing myself. I’d take a picture of a girl in a café just for the rough. Then they’d say, “Can you get a model like that?” Of course I couldn’t, because they would never just use the girl in the café.

ts: Also there wasn’t the same kind of relation to models at that time.

hp: There were very few models in the late ‘50s. They didn’t like people touching their hair or doing their make-up, and spraying stuff, you know? They’d go nuts! They did their own, mostly. It was really strange. The models were sort of upper-class girls, and they were mostly there to walk up and down with clothes on, not to be photographed in any way. Photographic models really didn’t start until the early ‘60s. I suppose Shrimpton and the ones who worked with John French, like Tania Mallet, were the earliest to get famous. Up until 1968, when I did the Pirelli calendar, we didn’t have a hairdresser or a make-up artist on shoots.

ts: We have to talk about the Pirelli somewhere. (Harri laughs) I was wondering why Duffy and you are the only ones who did two calendars.

hp: Well, I did one, and I was working with Derek Birdsall, who was the art director. He said, “Why don’t you do the next one too?” I’d just been working on a film in Los Angeles, and I’d seen incredible girls on the beach, surfing. I said to Derek, “Why don’t we just go out and photograph surfing girls? They’re really beautiful.” So we went to do it when all the kids were on holiday, but the schools were closed, and they all were somewhere else. When they were supposed to be at school, they’d be surfing. But they don’t mess around surfing when they’re on holiday. That was the reason anyway—it just happened like that.

The early Pirelli calendars were pretty tame. I think the first nipple was mine—and it was just one, in a corner of the frame.

ts: Your work seems connected to beach culture in the collective unconscious … Have you ever surfed?

hp: I’ve tried to surf, very badly, when I went to Los Angeles for the first time around 1965. I was doing titles and trailers for a film called Chappaqua by Conrad Rooks. Allen Ginsberg was in it, as well as William S. Burroughs and Ravi Shankar … Ornette Coleman did the music. There were all sorts of strange people involved. I took all of the rough cuts of the film from Paris to make up the trailers. When I got to New York, they took the film from me at customs. They wouldn’t let me have back until they had looked at it. It had nude pictures in it, and god knows what. So I went out to California.

ts: And what happened there?

hp: The film was going to be made by Universal, so I was put up in the Beverly Hills Hotel. But I had nothing to do! It took about six or eight weeks before the film got to me. I was messing around with musicians and people like Artie Ripp, the folks at Buddha Records. I was loose on the beach! Kids were surfing all the time. It was a drugs and rock-and-roll sort of time. We were always on the beach, stoned and surfing and—well I wasn’t surfing, I was just hanging out. I was so impressed by all of that beach culture. I sold the idea the following year to Derek for the calendar project.

ts: And where did you end up shooting it?

hp: His friend had a house that used to belong to Victor Mature. He was a screenwriter. I think he wrote The Dirty Dozen. It was this big, rambling house full of rats and god knows what else. And it had a big swimming pool. They’d gone bankrupt, and there was this big sign on the gate that read, “No traders.” We stayed there for maybe three weeks doing the calendar. We never had a model—we just used girls from the beach.

ts: That sounds amazing—and so lightweight! Today, they’d need an entire hotel to fit the crew. Actually, I’ve never seen you traveling with more than one assistant.

hp: When I did the Pirelli calendars, I didn’t have assistants, and I loaded my own film. But that was normal.

ts: Did you have any idea then that the calendar would become so iconic?

hp: Not at all. The early Pirelli calendars were pretty tame. I think the first nipple was mine—and it was just one, in a corner of the frame. They weren’t really wild in any way. If I had to rate it, I think it went Bob Freeman—his wife was the model, Duffy, Peter Knapp and then me.

Pirelli Calendar, 1969.

ts: In my opinion you are also very connected to pop art culture.

hp: I was brought up in the beginning of all that in late ‘50s. I was probably influenced a lot by so-called pop culture after the war. People started inventing things because they had no money. There was this creativeness in English clothes, and probably the beginning of prêt-a-porter. Before the war, in ‘55, I was 20 and models were all 30 years old and from middle or upper class families. (Thirteen-year old girls were really not it.) Then in the ‘60s you had working class girls, like Twiggy. Manufacturers, those selling the clothes, were not working class people—they ran the shop in their Sunday best. Vogue was fashion, and fashion was for selling clothes, but only to people with money, because no one else could buy them. Kids definitely couldn’t. Then after the war, there were all these army surplus shops. All the creative kids started buying clothes there, dying them, cutting them up. They were really the beginning, but many don’t realize that it started in a weird way. There used to be this incredible, beautifully made, plum colored jacket that was made for doctors. Everybody who was anybody at that time had one. You had to go searching for them at surplus stores.

ts: So you had one?

hp: Of course! (Laughing)

ts: Was it at the same time that you used to drive a racecar?

hp: Oh no that was earlier. I used to have a scooter, in the ‘50s.

ts: What generation do you feel most a part of?

hp: I suppose the beat generation was the one I was part of. They were the ones that were really interesting to me, you know, all the Kerouacs and the Burroughs, and all those sorts of people. All that era in the mid to late ‘50s was fascinating. Then pop took over and we had Allen Jones and all those so-called pop people. I was mixed with them. Following that was the Beatles, who came after me in a weird way. They were almost kids. Well, they weren’t kids, but it felt like I was of this generation before. I wasn’t a teenager when they turned up.

ts: You ran with them?

hp: Yeah, in the old days, and the Rolling Stones, they used to play in two different night clubs in London. The Stones were at this place we always used to go to. This was in the beginning in London, when they were putting out very early records that became very popular. I didn’t know them in Liverpool, but when they came to London we used to go to the same clubs.

ts: You also used to play music …

hp: I started in a brass band as a child. I did the trombone first, classical. I went to the Guildhall School of Music in London.

ts: You wanted to be a professional musician?

hp: I did. I played in the brass band for nearly three years between eighteen and 20 years old. We played classical music and jazz. At the time I got so fed up with it. I probably had dreamt that playing in a jazz band was like staying up all night stoned, and in reality it was just really hard fucking work. Everyone was just waiting to go home. I wasn’t playing the sort of music that I really wanted to play. It was better playing when it wasn’t for money. Then suddenly I just stopped, really quite quickly, and moved on.

ts: You’ve been in France for a while now though, 40 years?

hp: I’ve been here for 30 years. I used to come a lot before. Then I got involved with Genevieve, I suppose 35 years ago, and we went back and forth between London and France for a bit.

ts: I was talking about you with Albert Watson recently he said, “I remember I met this guy in the ‘60s.” He found out you had a French account and he found it very chic.

hp: (Laughing) I like that!

ts: I was working with this one model whom you had worked with for Muse recently and she was telling me, “Oh yeah, he was so cool! Very old school! It was like being in the ‘90s!”

hp: That’s good! (Laughs) I used film and they weren’t used to it. I processed it myself. Actually, it was probably processed in New York and was scanned and printed here.

ts: How about retouching?

hp: Well now I’m sort of used to it and I like it to some extent. Most of the old stuff was never retouched at all. There was no way to do it.

ts: Your girls always look real.

hp: Whereas now they’re not real anymore. I’m not against it. I am against the excessive retouching where the picture is made with the idea that it’s going to be retouched. I can almost find myself saying, “Oh well we can retouch that afterwards.” Before you could never do that. You could only crop. You couldn’t get rid of marks and things. Now when they’re overly retouched, I find it a bit strange. It’s in almost everything. Even if you don’t do it, someone else will.

ts: What’s your relationship with technology?

hp: It’s very bad! I think it’s great, but I’m so out of touch. I’m so not capable of using it. Sending emails, doing a little bit of retouching—I’m waiting for you to teach me. (Laughs) I do appreciate it though. I’m not against it in any way. When I look around I’m a little bit alarmed by the fact that it seems like people who have no real skills are given the opportunity to do things they don’t know how to do. They are asked all the time. Like small companies print their own stuff and it looks really bad. Now anyone is better than you or me. People can stand behind you and say, “No I don’t want it like that,” and go off and do it themselves. It is demeaning graphic design, but I’m sure the very good ones stand apart. It’s like the times when everyone had a guitar. After a while, the goods ones stand out and everyone else puts theirs down. I’m also a bit nervous about where all digital information goes. The fact that it swims in all directions rather scares me. And it can disappear too. I really like to have a bit of film in my hand when I finish doing what I’m doing.

ts: What about your archives? Where do you keep them and are they classified? Do you go through them?

hp: They’re half-classified. I’m supposed to be doing that now, going through them. If you look over there, there are thousands of boxes. A lot got burned years ago.

ts: In storage?

hp: I put together a whole collection of pictures for a book on women that I was going to do. I went to Australia, and while I was there, I left the house to a girl who was having some cancer problems. She freaked out and burned the entire thing. When I came back, the lady from upstairs said, “Oh! You’ve had a bonfire in your place.” I had these collections of masks that I had brought back from Africa and they were frightening her or something. She decided to burn them all to garbage, along with chairs and all sorts of stuff—it was crazy!

ts: That’s horrible.

hp: That set me back a little bit, but it wasn’t that bad because I kept carrier bags full of reject transparencies. They were all loose though, so I have to go through them again—because of course I didn’t go through them very well in the first place. In one way it’s good because they were pictures that I couldn’t have used back in the ‘60s, and they’ve not aged. Back then, when I was taking pictures for the client, or for myself, I would just throw them out. I knew I couldn’t print them. They weren’t right for the time. I don’t mean in that way that they were too sexual or anything, but now, you know, you can have photos of people with hair in their face and prop sex throughout. Things like a black person and white person together in a photo was not really acceptable. In America in the ‘60s, there was still a lot of really bad racism going on.

ts: When did you start taking pictures of black girls?

hp: I messed around, playing in jazz bands and whatnot a lot, and I had a lot of black friends. I’m completely against racism of any sort. I couldn’t understand why I couldn’t have a black model or an Asian model. But it was quite hard to get at times, and to get one on the cover was even harder. There were only one or two black models around. A few of the girls that I used were just good friends of mine.

I think Nova probably was the first women’s magazine to talk really intelligently.

ts: We were talking about politics in your pictures. It’s very common to see black models or models’ breasts now. Were you doing it to make a statement?

hp: We made some political statements on purpose. One cover of Nova that we did with a black girl on it, said, “I may look pretty but would you live next door to my mother and father?” So we were doing political statements then but that was not so much my photography as the policy of the magazine. It was just the sort of magazine I was working for. If I could sneak something in that made some sort of comment, I would. Not everyone notices things like that, though.

ts: Tell us about Nova. Why do people always refer to it?

hp: I think it probably was the first women’s magazine to talk really intelligently. A lot of the best writers were working with it. Before that most women’s magazines were really quite shallow. It came out in ‘65 so I suppose up until then most women’s magazines weren’t discussing the women’s liberation that was in full swing. It was the first magazine that started to pay attention. It wasn’t a fashion magazine either. Fashion was only secondary for Nova; it was in there really because of me. The original concept was so full of text that I said, “It’s gotta have a dozen pages of color somewhere!” We were going to do art or something else but we did a couple of fashion things and carried on. There was never any control over the fashion. There wasn’t anyone trying to sell ads or do anything while I was there. In the end it became too successful, and not successful enough, for its own good. Successful enough for people who control magazines to be interested. It was like a test magazine to see if there was a market for intelligent women.

ts: How the advertisers changed the business?

hp: If you want to take natural looking pictures today, it’s difficult. Sometimes I can find old-fashioned pictures that look like proper photographs. It could be your girlfriend laying on the couch whereas now there’s no way. Movie people were okay because they dressed the part. You used to dress the girl as if she were a real person—now you dress her as a clotheshorse, to sell things, purposefully and obviously. She’ll have too many bangles on, too many things, a buckle, a belt and a hat. They don’t always match either. You very rarely see a picture that looks like a natural person. It wasn’t quite so bad years ago. I could find pictures that you wouldn’t know were done. I think is has changed. Just throughout my career, the fact that now everything has got a sign on it so you know where it came from. Before, the only thing with a logo on it was Louis Vuitton. Now everything has got a sign on it.

ts: Models always seem very comfortable with you.

hp: I don’t know—I hope they do. I’ve always been all right. I haven’t had any real problems. When I was 20 years old or something I was the same age as the models. Now I’m like their grandparent. Things have changed a lot. At that time I was part of their lifestyle so I had a much closer relationship. I knew most of the models I worked with in the ‘60s. Now I don’t know any. Nobody does anymore. Everyone used to have their own studio too. You could take a picture of somebody in the middle of the night or any time. You could take a picture just for fun, for the pleasure of it. Now you must arrange a studio just to do anything. There are still photographers with studios but before everyone had one, even if it was just a room in their house. I remember Duffy had a room in this Victorian house he was living in. His front room was his studio. Bailey too. I used to speak to art directors; they used to ring me up. And if I wanted a model, I could talk to somebody in a bar. I’d just ask for them to come and do a couple of pictures that night. They’d come and do it just for fun. They didn’t even take money. Now we must go through agents, and god knows what, even if we know the people.

ts: How about this photo book you told me you wanted to do?

hp: That’s what I’m supposed to be doing, but underneath the stairs, you see there, I’ve got more than 50 plastic bins full of transparencies. The trouble is, now I’ve sorted them, so they’re roughly in their correct bin. They’re still mixed a bit. I have my own deadline.

ts: Are these all ones that you’ve already printed or published?

hp: Oh no! There are ones that’ve been used but most of them are not. I think most of the good pictures are not necessarily fashion-y things. But I’m known for certain images so if I don’t show those types of images, people won’t understand. And also Genevieve and I spent ten years making books all over the place. That got us off the street. In that time we were virtually never at home at all—we were always traveling in Africa or somewhere.

ts: Doing travel books?

hp: I had a commission. This is Birdsall again, same art director. I worked for him for years. It was like a best friend sort of thing. We were graphic designers together at one point. One of his clients was Mobil Oil and they wanted to do a series of books on the countries from where they were, without being rude, taking oil. They were these coffee table books aimed at showing the crafts and arts of these particular places, but they wouldn’t say Mobil on them. They were for giving away. We went to Micronesia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Japan even. There was a very good, really proper anthropologist, from a museum, to write the books. They were very well done. For years they’d send us to just wander around the world. We took any picture we liked … that was in the ‘70s. When I came back, everyone thought I was dead. I was always threatening to go and paint or do something else. I loved doing fashion pictures but I was never part of the scene. I never respected fashion as a business, especially the buying and selling—it really made me quite sick. I really used to detest the shows as well. The people in magazines that were so serious about it, I could never quite buy into. I was never anti the clothes or the design—just the whole global nonsense. I’m rude about it, but I swim in it.

ts: I always felt like in this business I don’t go out with the right people, I don’t take the right drugs, I don’t have sex with the right girls, you know?

hp: I think that’s part of it. I’ve never done that either. I’ve never been part of the scene but I’ve worked a lot in it.

ts: When I was just out of school, a big fashion art director told me that the first fashion show he went to changed his life. I was expecting the same when I went to my first fashion show, but it didn’t change anything.

hp: That’s another thing, the shows you see now, they’ve changed since the ‘60s. It used to always be a row of gold chairs in a hotel room. Ladies would sit as the girls walked around them. There was no music or anything. They just held their number up, and the announcer said, “This is number seventeen made of mohair.” The first fashion show I took pictures for was for Vanity Fair in London. I quite like the pictures because they’re so straight. I just stood over in the corner.

ts: Do you have any connection with the new generation of photographers?

hp: I do meet new young photographers sometimes. I see their work around in magazines and things too of course. I quite like some of it but I don’t meet up with photographers very often. I still look at fashion magazines but I don’t have a particular one that I subscribe to. The established magazines have less to offer now than the kids’ magazines that don’t pay or do anything—and they’re so set in their ways. I find a lot of interesting so-called young magazines. There’s always some crazy type or something to look at. I find them a bit alarming mostly, but I quite enjoy buying them anyways. The content is really scary, though, as well as the literary styles.

ts: There is no snobbishness, at all, in the way you work.

hp: I think I just like taking photographs. I never understood this idea that if you work for one magazine you can’t work for another. That idea does exist even if it’s not written down. It used to be that if you worked with Vogue, you couldn’t work with anyone else. Not so many people have contracts with them now. But in the past, if you had a contract and then you worked with someone else, you were judged as a deserter from the cause or something like that.

ts: This reminds me that when Newton got his first assignment with Vogue, he was credited with a wrong name.

hp: That’s classic! Hans (Feurer) and I are always getting switched. I get credited with his work and he with mine. I don’t know how it happens. People are always bringing me pictures of his saying, “Can you do a picture like this?” I say, “Why don’t you call him and ask him.” He was an art director too of course. There was a book, and this really pisses me off actually—I was going to do something about it. There is this little fashion book that I found with my pictures in it. It’s one in a series and it’s written by someone who’s supposed to be an authority on fashion. All of the credits are wrong! It’s interesting to see that these sorts of books get published—you just wonder, why? You read it and it’s absolute crap. They don’t even ask if they can use your pictures. I found this book by accident. I was going to write to them and be rude to them.

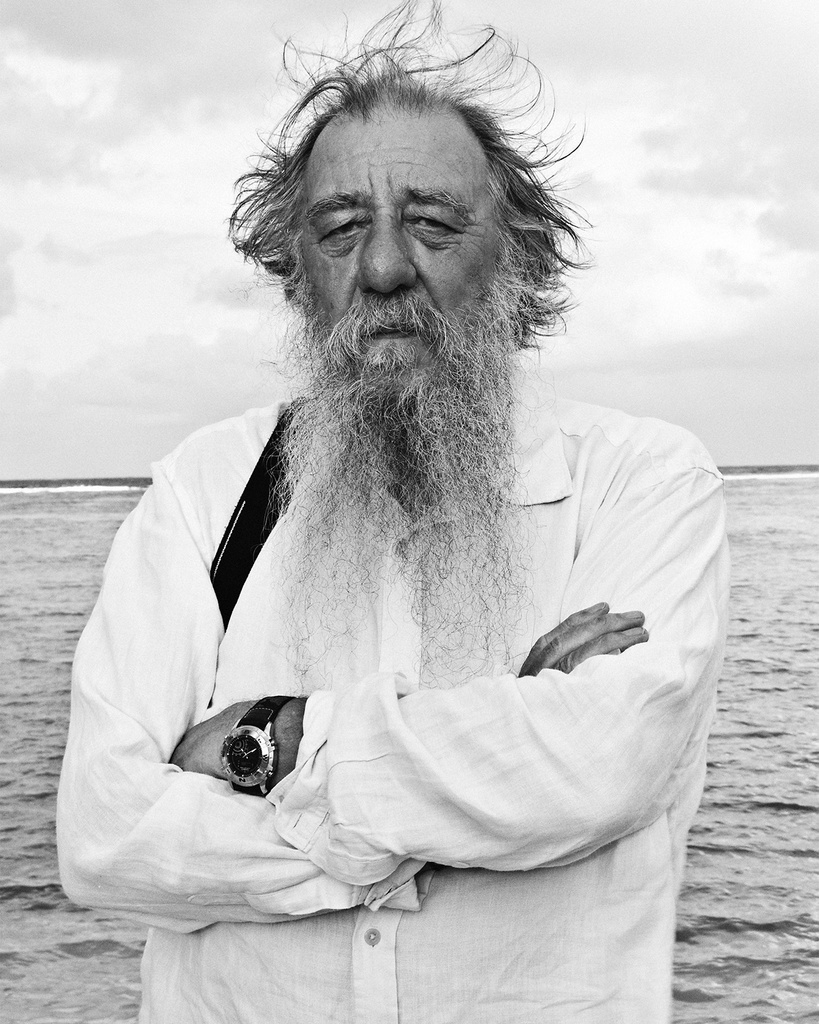

Harri, 1995. Photo: Thomas Schwab

ts: You did a cigarette commercial a while back. That’s such a great story. Can you tell us about that?

hp: That was really slightly special because I knew that the end of advertising for cigarettes was going to come. It was a Dutch company, Caballero Cigarettes. First of all, the art director went to Singapore for about four months to find a skipper who owned a boat to rent it and to write the name of the cigarettes on its side. He found a small racing yacht, enough to hold three or four people. It had to be sailed to Thailand where we were doing the pictures. Then they rented a fishing boat to take pictures of the boat from. They also got a really big French yacht, with a chef and everything on it, who cooked and did everything for us. I think we spent four months or something like that for 20 to 40 pictures. When I say 40, I mean we took hundreds. We had two weeks off on holiday in the middle of it. They had to bring the model’s boyfriend over because she was sort of pining after him. We just wandered around the islands, sailing about. We had a model that didn’t want to smoke because he was one of the first people with AIDS. Although he didn’t say he had AIDS—it was before that time. He decided he could only eat lobsters, so that’s what he ate every day. He died quite early on. We photographed at six in the morning and five in the afternoon, as usual. Incredible trip. I mean, it was really mad! The art director and the creative director came out with their wives at some point and people kept coming. It was sort of like a party. You can’t believe the stupidity of these pictures. They went on packaging. They went on film. Can you believe it?

ts: A friend of mine, who used to be a big copy writer in the ‘80s, told me that when they were working on storyboards at that time, they used to draw palm trees somewhere just so they could go on trips!

hp: Oh yeah and we’d fly the model out three or four days before the shoot just in case she got burnt. And of course they always got burned immediately, so in another three days we’d shoot when she’d healed.

ts: Are you ever afraid of failure?

hp: I am of course. I’m always thinking things are not going to work. Especially working with film, I’m always slightly nervous because you never know if they’re going to come out. I don’t like too many Polaroids either.

ts: You’re always quite modest. When you’re done on set, you always say, “There must be something somewhere.”

hp: Doing pictures, I’m really quite nervous about whether it’s going to work or not. I wonder if I’m doing it the best way possible—is there a worse way to do it? If you build a set and then it doesn’t work, you’re really stuck! Every now and again I have ideas that I try to do and they don’t work properly. That pisses me off a lot. Sometimes I think something is a good idea and then I don’t do it as well as I would have liked. I’ll think it’s all right, but I should have spent more time on it. I should have done it somewhere else or with a different model or something else. You can’t redo the idea because it’s been done so you must move onto another.

ts: What is your relationship with your collections? Would you consider yourself a collector?

hp: Not really. I think it just happens to me by accident. I can’t throw things away and if I see something I like the look of I tend to pick it up to collect. Apart from the things that are broken or half-cooked, I just keep them. I have one incredible thing, just by accident. Years and years ago, before I met Genevieve, I found this toy car. And later, I was walking on a beach and found another. This one had been worn by the sea. It was the identical car to the other one, just worn out.

ts: Incredible, where did you find it?

hp: I don’t know, somewhere on the beach in India some 20 years ago. I picked it up just to keep it—I love picking things up from beaches. From the sea and the rocks, it’s just gotten smooth. I went to put it in with all the others, and I realized that it was the same as another I had.

ts: Do you observe any religion? Your wife is a Buddhist…

hp: No, I’m not religious in any way.

ts: Your beard is not related?

hp: Years ago I decided I wasn’t going to shave, that’s all. I couldn’t see the point in it, so I stopped. That’s all it is.■