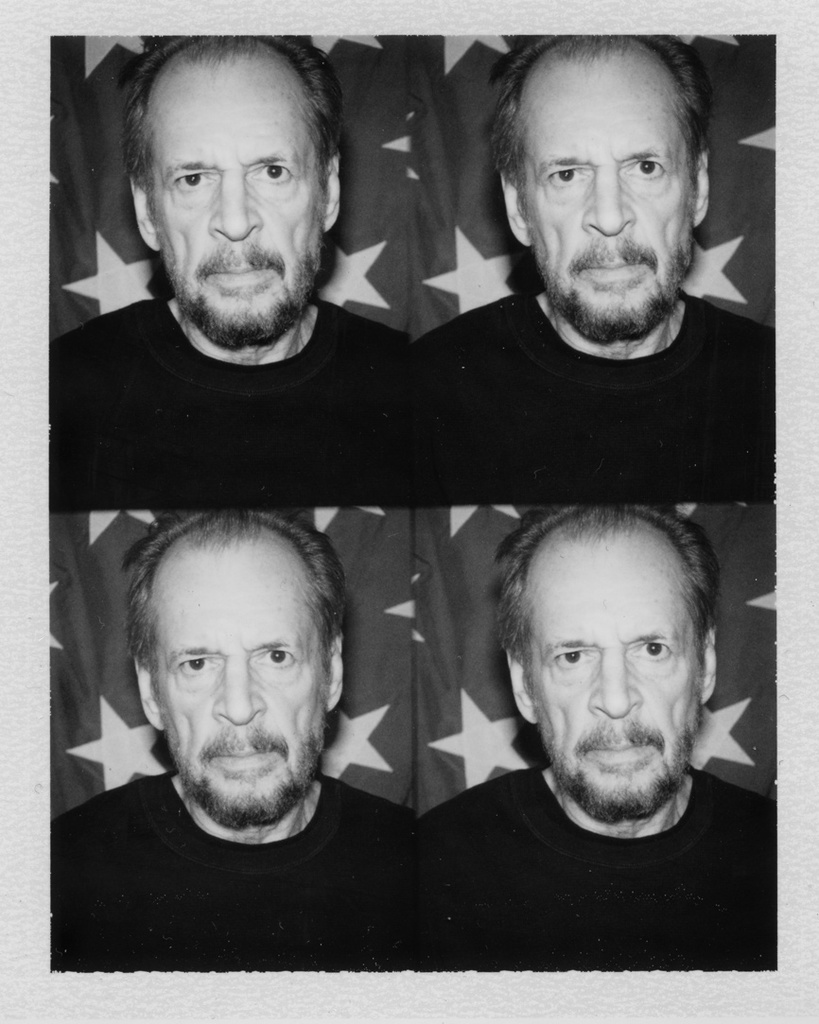

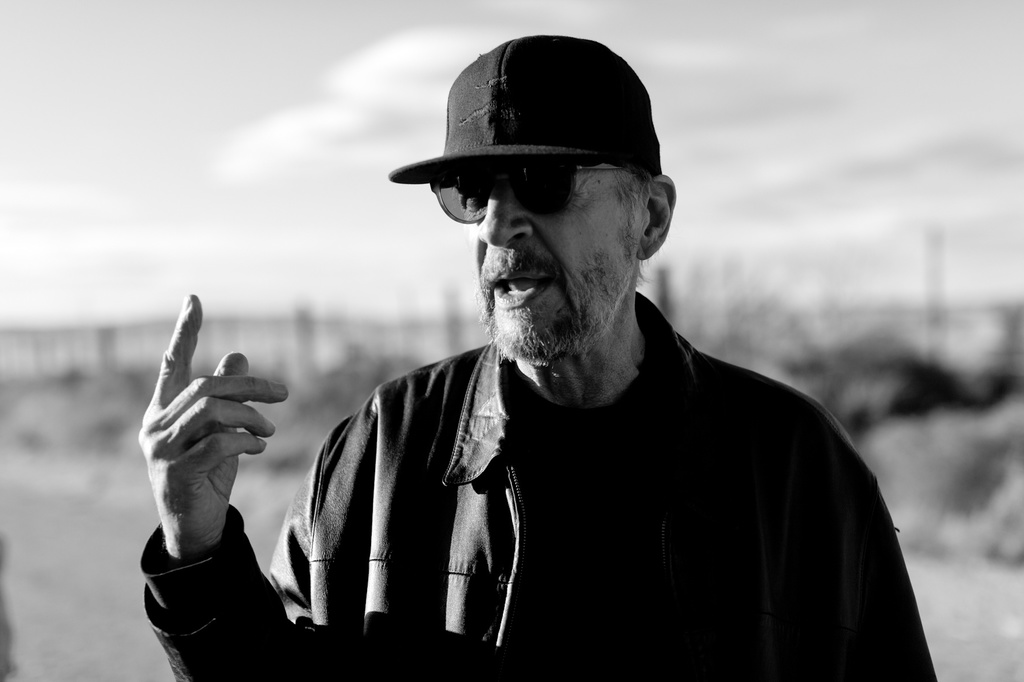

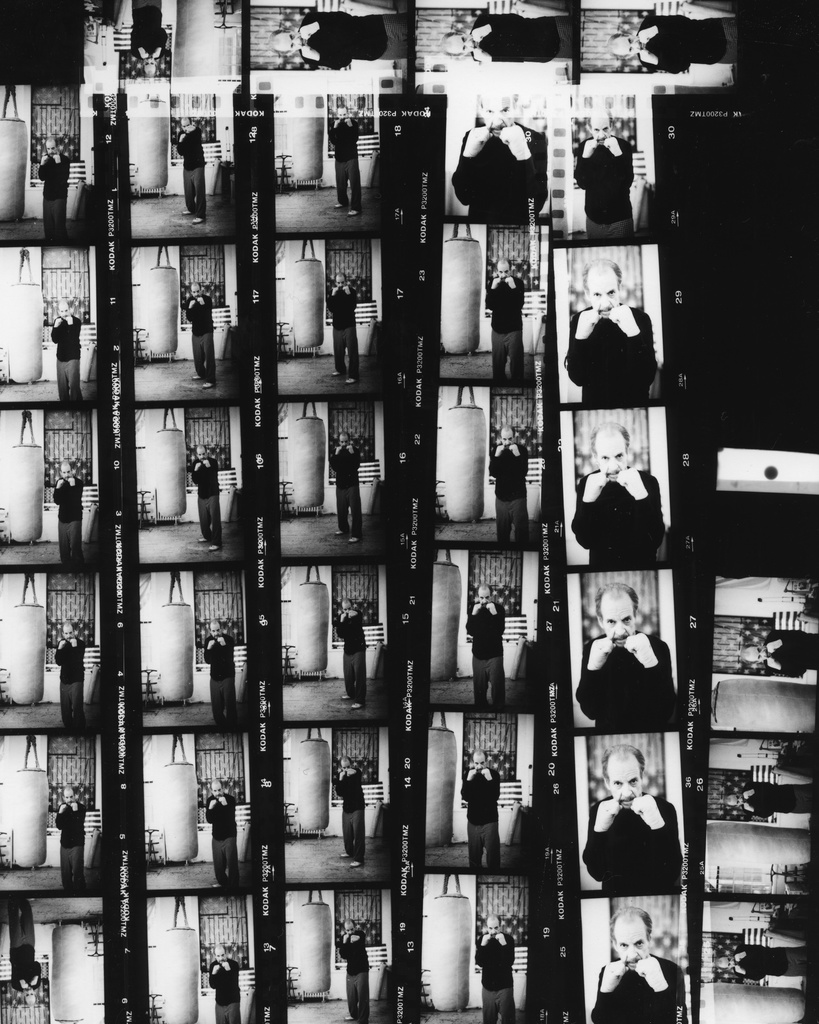

If we’re casting votes, Larry Clark is definitely in the running for sexiest 69-year-old alive. To keep up appearances, Clark has taken up Veganism and boxing, disciplines that he claims have given him enough energy to work for 19 days straight, as he recently did on the shoot for his new film set in Marfa, Texas. But beyond his physical regimen, Clark’s latest renaissance is manifested in his work. Marfa Girl, a hot-weather coming-of-age West Texas tale featuring freight trains and spiritual healers, boy bands and border patrol cops, may be his most personal film to date. It’s personal, in that it echoes and contemporizes themes from his notorious book Tulsa, which established Clark’s signature voice and visual language. The mosaic of sex and mushrooms, guns and skateboards, bonfire deserts and translucent skies finds footing in Clark’s indelible style. If anything, Marfa Girl is an ode to America, a gritty romance that reminds us of the pioneer’s burn and cultural polarities that groomed this country.

We met on an overcast January afternoon at Clark’s favorite Italian bistro in TriBeCa to talk about inspiration, catharsis and his plans for his 70th birthday. Over a late lunch, Clark told me about The Smell of Us, his first film set in France, which he described as “Kids in Paris,” plans for a Marfa Girl trilogy, and his commitment to keeping his creative output in overdrive. “I was working fast and working hard,” Clark said of the Marfa Girl shoot. “I don’t want to die on the set making a movie, but maybe I will.” During a cab ride to an exhibition on boxing legend Arturo Gatti in Chelsea after lunch, Clark was coolly reminiscent about life and the lessons and lesions that have defined his journey. He has been a diehard New Yorker since the ‘70s and has been a direct witness to the city’s transformation. As we drove through a Manhattan sunset, Clark admitted, “I spend all my money on juice now. I’ll spend maybe $150 at Organic Avenue, but I just tell myself that I don’t do drugs, so it’s okay.”

anicée gaddis: What are you working on at the moment?

larry clark: I’m going to France to make a film, in French. I had a retrospective in Paris where I had this idea to make a film. The original idea was almost Kids set in Paris. I was standing in the back of the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris (Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris), just next to the Palais de Tokyo. You know it?

ag: Yes.

lc: The front is this incredible façade, and in the back it’s kind of a no-man’s land and all these skaters go there. They skate, and they graffiti the place up. I saw this scene and it reminded me of Washington Square in ‘94. I said, “Wow, I wonder what happens to these kids when they leave,” because it was all different kinds of kids from different social classes. I had this idea and I explored it with a young poet, Mathieu Landais, who wrote the screenplay for me. It’s called The Smell of Us. I’m making it now. There are parts for great French actors. There’s also a part for a 60-year-old woman. It’s contemporary, and it’s of the moment, so I’m very happy.

ag: And you mentioned a Marfa Girl follow up after that.

lc: After I do that, I’m making Marfa Girl II, as part of a trilogy. I wrote and directed the first one and I’ll do the same with the second. I’m having fun because of where the last movie left off. It’s interesting to see where the characters are headed psychologically as they move forward.

ag: Marfa Girl definitely had a cliffhanger ending.

lc: Yeah, well, there’ll be more. I’m doing a trilogy because the kids are sixteen now. Marfa Girl actually was shot on Adam and Mercedes’ sixteenth birthdays. They were born in March one day apart. They’ve known each other since they were eight years old, so it’s pretty interesting. In the next one, they’ll be seventeen, and the third one, eighteen. So we’ll see what happens to them. I don’t know yet because I’m making it up as I go along.

ag: I remember the last time we talked, when you had just put out Wassup Rockers, you said you wanted to take the audience on an “unexpected joyride.” What did you have in mind for Marfa Girl?

lc: Marfa Girl was really serendipitous. I went to visit my friend, the painter, Christopher Wool, and his wife, Charline von Heyl. They have a place in Marfa. They live in New York, but they go down when they can. There’s an art colony there because of Donald Judd, and there’s the Chinati Foundation, which is in an old army fort that they bought and turned into galleries and permanent exhibition spaces. Right on Main Street, there’s a permanent gallery for John Chamberlain. Anyway, there’s this art community and then, as you know from the film, they put the headquarters of the border patrol for West Texas there. So it’s this little town in middle-of-nowhere West Texas with 1,800 people. It’s white ranchers, the locals and Mexican-Americans who were born and raised there. Plus, Giant was made there, which was James Dean’s last movie. That was its original claim to fame. It’s a journey to get there … you have to really want to go.

ag: What were some of your first impressions of Marfa?

lc: I wondered what it was like to grow up there, and really not have any access to anything except the Internet. You know the world, just like any other kid, and you’re smart and hip and you know what’s going on, but there’s nothing going on there. It’s really isolated. They also pretend there’s nothing going on, there’s not teenage pregnancy, there’s not all this stuff, but of course there is. It’s like any other place but it’s stuck in this ‘50s mentality. They still paddle kids in school and it’s very, very Christian.

ag: It sounds like a time warp.

lc: It is a time warp. It is a microcosm of what’s going on in America, where whatever problems we’re having with the economy, unemployment, etc., people want to always put it on the easiest targets. So they blame everything on the immigrants who just want to come here and have a life. People still think the streets in America are lined with gold, that this is the land of milk and honey.

ag: How did you come up with the storyline?

lc: My basic idea was to have this kid Adam walk through the movie as an ingénue, and all these things happen around him. I took my diary and made a 25-page script just so I could schedule the film. Then I wrote it as I went along. I just woke up every morning and wrote.

ag: I love the scene where Adam gets paddled at school by his teacher for sleeping in class, and then paddled right after that by an older woman who is trying to seduce him—all on his sixteenth birthday.

lc: That was my first idea—that he would get paddled by an older woman and spanked in school. It’s funny because they wouldn’t let us film in the school. They probably Googled me or something. We were locked in to film there, and then we got denied permission at the last minute. So we went to the next town, Alpine. The principal was great and they were all very nice to us. After we made the film, some of the townsfolk in Marfa were saying, “Oh, this guy Larry Clark is coming in and exploiting our town.” They asked, “Why is he picking Adam and Mercedes to be in the film? These aren’t the greatest kids.” I mean, did they expect us to go in town and find the honors students? It doesn’t work that way. You find kids who are charismatic, and whom the camera loves.

ag: There’s a great line from Adam when he says he wants to move to San Diego and become an actor when he grows up, “If I grow up.”

lc: That is, if Miguel doesn’t kill him first.

ag: It’s a moment of comic relief, but it also brings the reality of his future prospects into sharp focus.

lc: Exactly. And you know, a few weeks after we finished shooting, a teacher got arrested for fucking a fifteen-year-old student in her classroom. A 28-year-old teacher had sex with a fifteen-year-old boy. In the newspaper, there was an article where it gave her name but not the kid’s name. But everyone knows who he is. Apparently, a few hours after, he told all his friends. So that’s how she got arrested. I got a laugh out of that, though it isn’t something to really joke about. But come on, they won’t let me shoot in the school where the teacher is fucking the student?

ag: What kind of camera did you shoot with?

lc: A Cannon 5-D. It’s a very small camera, and I had no idea how it would do or hold up. The director, Marco Mueller, came to New York and wanted to see my film. We were color correcting and projecting it on a thirteen-foot screen. So he saw it, and wanted to show it in Rome at the Rome Film Festival. He invited us to the competition. They were screening maybe 80 movies, but only fifteen were in the competition. And then we won the festival, which was amazing! It was really a shock. It was screened on the biggest movie screen you’ve ever seen. I was really nervous. But it was sharp as a tack, and you couldn’t even tell it was digital. It looked like film. Marco said it was going to be a lesson for all young filmmakers about what you can do with these cameras.

ag: How long did you film, start to finish?

lc: I shot the movie in nineteen days. I was working fast and working hard. Apparently I can do that cause I did it, once again. I’m getting too old for this, though. It’s gonna kill me. I don’t want to die on the set making a movie, but maybe I will.

ag: What did you take away from the experience, emotionally or otherwise?

lc: I had more fun than I’ve had on any other film—so much fun. I just did whatever came into my head, thinking about my whole life, things that had happened to people I knew. I always wanted to make a movie about a bad cop. I just kept making him badder and badder and badder.

ag: Jeremy St. James is great in that role. He just keeps sinking lower and lower.

lc: Yeah, he plays Tom. I made him go lower and lower, and then I just went all the way. I would tell the actors as we went along. I would tell them right before we shot. I told Adam and Jeremy I had an idea for this scene. And they did it. It was scary.

We all used to go to the Odeon. Once a month, we’d have nights together. We’d go to Richard’s and we’d bring videotapes, something to show everybody.

ag: You’re talking about the scene where Jeremy offers to give Adam a ride home and then takes him to an abandoned building instead?

lc: Yes. It was scary for everybody—for me, for them, for the crew. But I knew this kid in Oklahoma who had experienced something like that, though not exactly that. A cop had arrested him for burglary and the kid was going to go to the penitentiary but the cop let him off.

ag: How did you come up with the motivations and back-stories for each of the characters?

lc: My idea was to contrive a situation where each one got to tell a story about their childhood. I’ve always thought that what happens when we’re children and adolescents forms us as adults and really has a big impact on our lives. I wanted to give everyone an inkling of why the characters behave the way they do. But Tom got out of hand, for sure. The Marfa girl got out of hand. Everyone gets out of hand! And boy—Adam!

ag: Adam seems to be a leveling force at the center of all the crazy chaos swirling around him.

lc: He’s just a kid. I was really working him hard. He was running and skating and doing this and doing that.

ag: But he came out intact?

lc: He’s great. He’s ready for round two.

ag: How was the on-set chemistry between Adam and Mercedes? Their scenes together felt really unscripted and sincere.

lc: It was really, really good. They kind of fell in love. They had a little bit of puppy love on the set. I saw that happening, and I talked to my DP and said, “Keep the camera on them. Forget the scene, we’ll run the scene, but just keep the camera on them.” And if they were in the background, like when the band played, it was just magical. The scene where they make love is so tender and innocent. It’s totally different from anything else, you know? And I wanted it to be that way. It was the cutest thing.

ag: How did you decide on the other actors in the film?

lc: Mary Farley, who plays Adam’s mother, I knew in New York over 20 years ago. She’s Matthew Barney’s ex-wife. They used to have dinners with Cady Noland and Christopher Wool and Richard Prince. We all used go to The Odeon. Once a month, we’d have nights together. We’d go to Richard’s and we’d bring videotapes, something to show everybody. Anyway, I’d known her for a long time and she was living down in Marfa and she had this farm, a chicken ranch with her birds. I stayed there, alone in her house with the chickens, when she went to Austin to see her boyfriend. I’d go get two fresh warm eggs every morning. And I started thinking, “What if Adam lived here and Mary was his mother and he had chores to do before he walked to school?”

I don’t storyboard. I just made it up as I went along. I’m a visual artist, and I can make great images.

ag: The town of Marfa, what’s that like?

lc: The cemetery is still segregated. It’s just traditional; it’s the way it was. You had Mexicans, and you had Americans. There’s this great film, Giant, which is about racism and the young Dennis Hopper who wants to marry this Mexican girl in town. It is the worst thing ever. There are endless fights and battles. You should see Giant. It has Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor, James Dean, Dennis Hopper and Katy Jurado. It’s really great. There was so much racism back then, and there still is some, but nothing like it was. Mexican-Americans were like the blacks of the South. They weren’t slaves, but it was very segregated and prejudiced.

ag: Some of the images, especially the post-coital nude scene of the Marfa girl lying on a bed covered with an American flag, reminded me of shots from Tulsa. Do you make storyboards or rely on a more spontaneous approach?

lc: I don’t storyboard. I just made it up as I went along. I’m a visual artist, and I can make great images. I was just working. I was just on. I was in the zone, and hitting 25 three pointers in a row. I could not miss. It takes a tremendous amount of energy. I needed more energy, so I became a Vegan and I quit sugar, which is a big thing. Never eating sugar has increased my energy ten-fold. I wake up here (raises a flattened palm to the top of his head) and I stay here all day long.

ag: Who scored the soundtrack?

lc: The kid from the movie, Jesse Tejada, who was the one who played the chaos pad in the band. He stayed up all night and composed these pieces based on sounds from video games. I also used a more traditional composer for the rest of the music in the film, but Jesse was amazing. I’d never heard that kind of music on a soundtrack before.

ag: Mercedes is really striking on the film, both for her physical beauty and her downbeat charisma. What was it like to work with her?

lc: It’s funny about Mercedes. She’s absolutely gorgeous. She has wanted to be a model since she was five years old. Her makeup and nail polish, that’s all her own look. I had one day off, and I used it to do a fashion shoot for V Magazine. They called me—and they never call me—and I don’t do fashion shoots, but to promote a film I will. So they said, “We’re doing an Americana issue.” And I said, “I’m in Texas making a film!” And they said, “It was our dream to do something in Texas!” They flew down with racks of clothes and the stylist and a whole crew. I went out with my M9, my Leica, and did all those pictures in one day with the kids. The next thing Mercedes knows, she’s in this fashion magazine. It was quite satisfying to be able to do that.

ag: Do you think any of the kids will make it out of Marfa?

lc: I think that’s the dream of every kid there … to get the hell out of West Texas.

ag: What is one of the truest compliments someone has ever given you on your work?

lc: Well, after I did Kids, an extra from the film, this kid, stopped me when I was walking in Manhattan one night. He said, “Larry, I saw your movie.” And he said, “You know, it wasn’t like a movie. It was like real life.” And that’s the best compliment I’ve ever had, truthfully.

ag: What is one of your private joys?

lc: Well, it really all has to do with work, because I use everything I see going on around me in my films. And not to be corny, but my kids are my biggest private joy. I love to hang out with them. My daughter got married this summer in the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, and I gave her away. It’s so beautiful there. She’s very happy. My son’s coming in to town for my birthday on the 19th, it’s my 70th, so I’ll be with my kids and it’ll be fun.

ag: What are the birthday plans?

lc: There are a couple of parties. I’ll see my friends. And then I go to Paris, right after that. ■