asmeret berhe-lumax: What does photography mean to you?

malin fezehai: I think for me, photography is a way of telling stories. And it’s an excuse for me to partake in other people’s realities.

abl: What stories do you find the most important to share and tell?

mf: It varies. I think some stories I’m drawn to because I think they’re very important subject matters. I work on stories about refugees and displacement and dislocation around the world, but I also love telling stories about different cultural phenomena and people that do something a bit different.

abl: Which stories do you enjoy telling the most?

mf: I love telling stories about people and getting into their lives, following them around for a day and just partaking in their reality. And that can be all kinds of stories. It can be a refugee in a camp or a surfer in Senegal.

abl: Tell me more about the process that goes on before a project. What is the research that goes into it?

mf: It might be that I’m interested in visiting a certain region or a place, where I have a certain subject matter in mind. So I’ll do a lot of research about it and see what fits the bill. Right now I’m working full-time with the New York Times and I’m doing stories about subcultures, so I’m researching stories that are a little obscure and different in the place that they are at.

abl: And also with that, what is the post-production process in terms of selecting images or shaping how the story would be told?

mf: You have to edit and you have to try and see what the focus is that you want in the story. I took photos around that and also kind of editing the narrative now, which is a new thing for me because I just started writing. And so it’s a lot of figuring out what the things you want to highlight with your story are.

abl: Tying back to what you mentioned about New York Times subcultures, where do you start?

mf: I actually start with my friends because they’re out in the world doing stuff. And also they’re very much into subcultures, so I like to check in with people from time to time see if they have any suggestions and things like that. And then also I travel a fair amount so I feel like I’ve come across certain things on my path that fits the bill.

abl: What are some of the most memorable projects or stories that you worked on and how did they affect you?

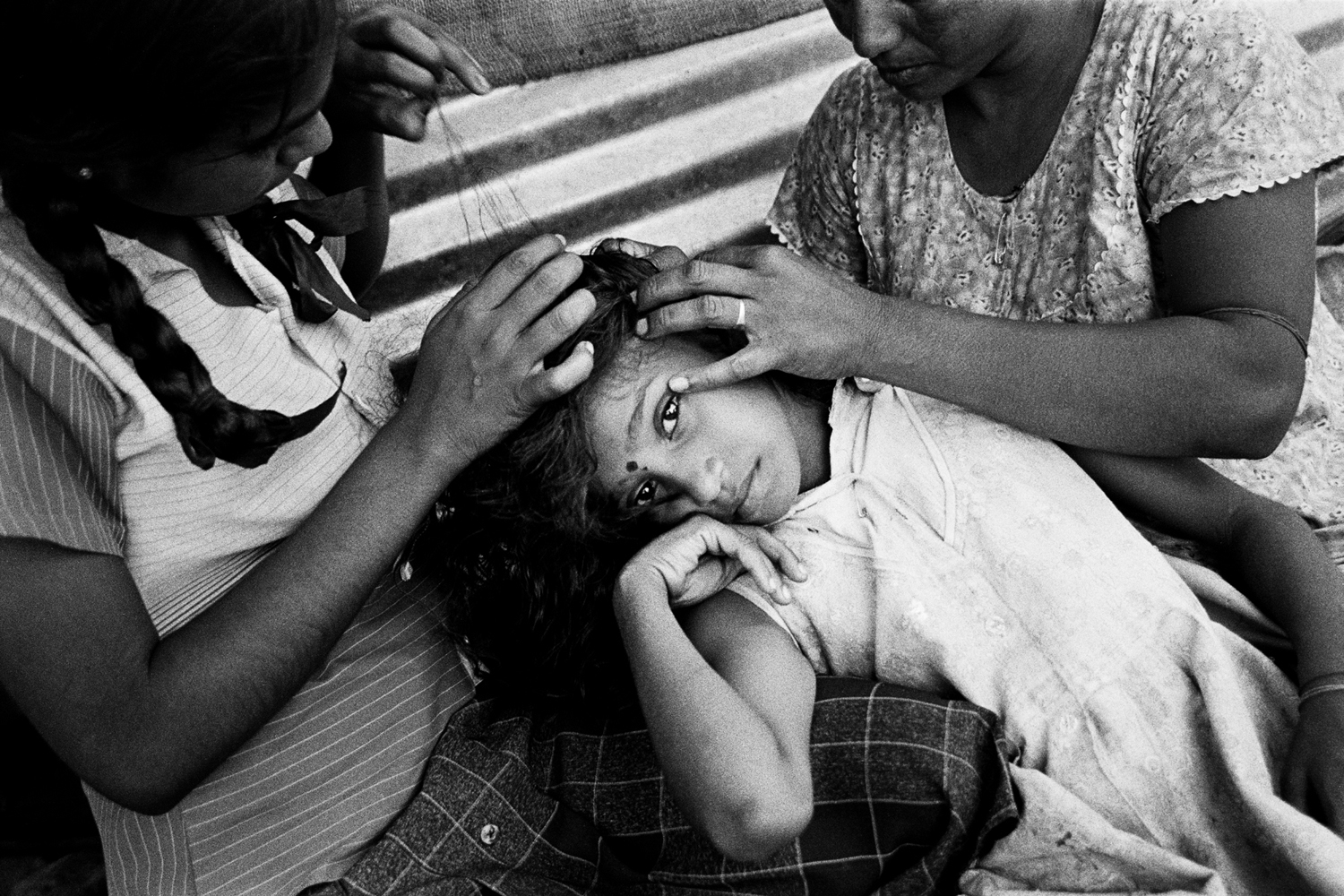

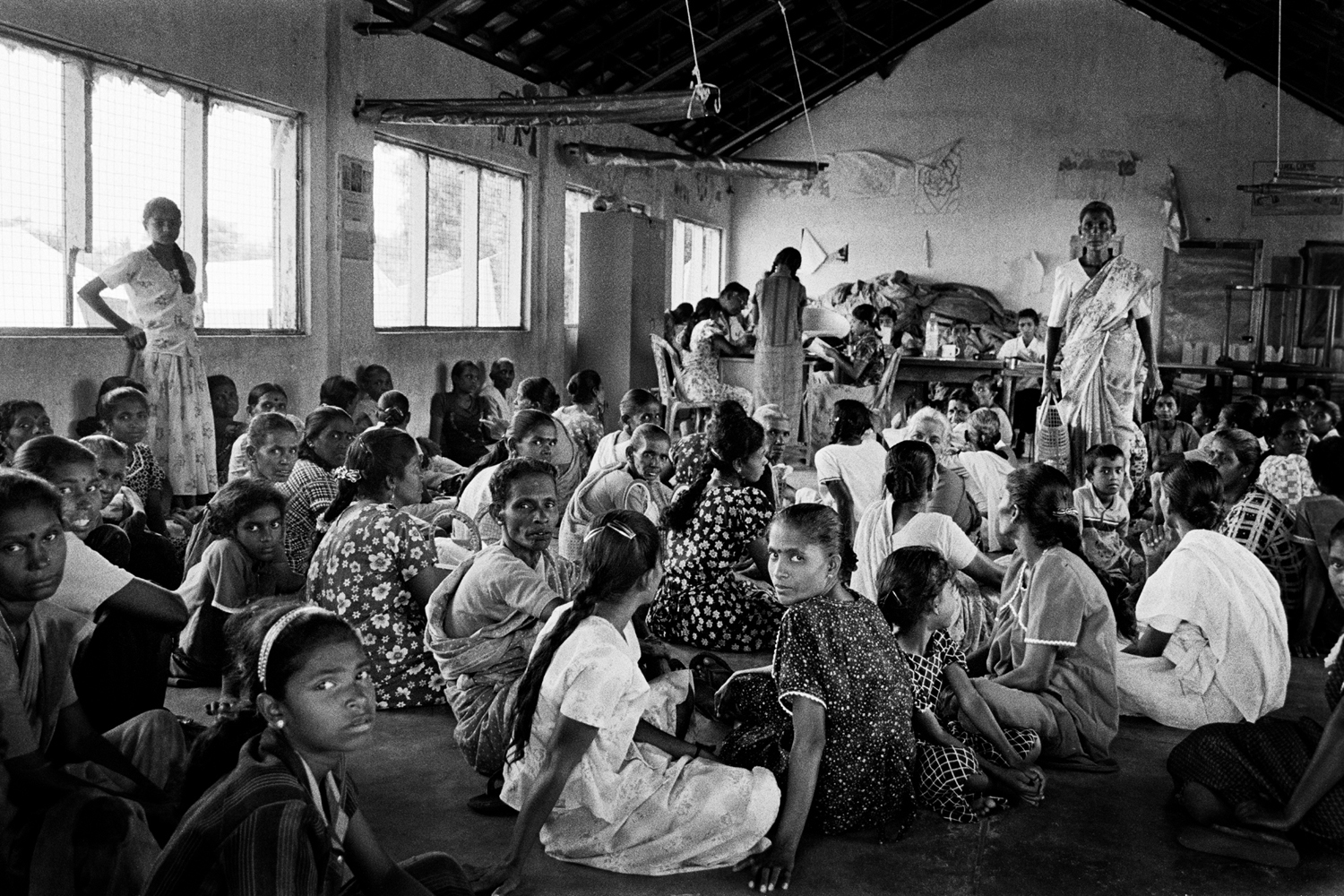

mf: I’d say the story I did about war displaced women and children in Sri Lanka because it was the first time I was ever in a refugee camp. And I feel like that kind of shaped who I was as a photographer. I learned a lot on that trip because it was the first time I was ever in a high-risk war zone. Just facing that reality while still meeting the amazing people who were working in those circumstances.

abl: It must be heavy and taxing to be there as a photographer and as an observer.

mf: Everything else feels trivial when you realize that you have the resources and the capacity to leave those bad situations and the people there can’t. Like I’m making a conscious choice to enter into those situations, and the people who are there don’t have a choice.

abl: How do you deal with it? Do you feel like the post-production work is part of the therapy?

mf: Depends a little bit on the project. There have been projects that I’ve felt were very traumatic and they were hard for me to go through the work afterward. But as a professional, you learn how to separate yourself a little bit emotionally. That’s actually what I would say is the bigger issue than even experiencing trauma, is the separation between you and life, in a way. Because when you’re in a very traumatic situation that you learn to separate yourself from that, but when you come back to normal society it’s hard to come back to life because you created a separation between you and whatever is going on around you.

abl: To switch it over to a lighter subject (laughs), you published a story about surfing culture in Dakar, Senegal. Can you tell me more about how that came about?

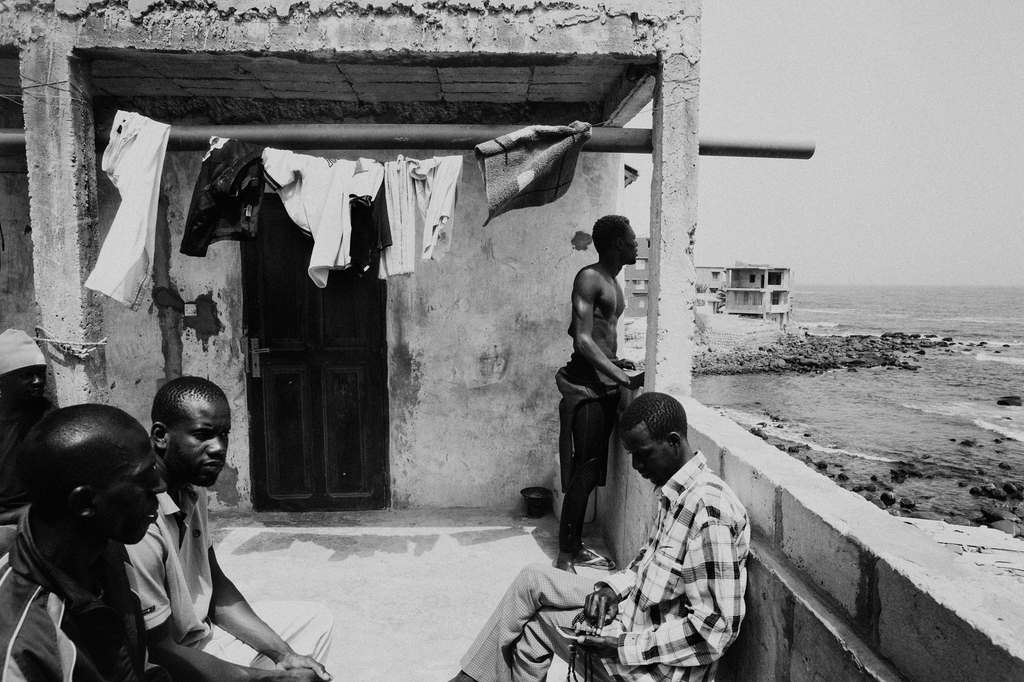

mf: So I was looking for different stories in Senegal because The New York Times magazine actually reached out to me and wanted me to do something for their Voyages issue—that’s basically where they have a photographer go on a journey somewhere. So I suggested a few stories, and I have a friend who used to live in Dakar and he used to surf there. So I asked him some things, and I put that down as one of the ideas and they really liked it. I also had just seen the movie Endless Summer and the first stop on the journey was Dakar, Senegal. I thought it would be a cool thing to go and see what kind of surfing community they have there today, and I wanted to focus on the Senegalese surfers.

abl: What did you find when you were focusing on the Senegalese surfers? Because I think the general perception of surfing culture has been very West Coast California America.

mf: You know it was interesting because there are certain surf culture things that were still very apparent in Senegal, like the hand gestures (laughs). It was cool to see these guys, some who didn’t even speak English, adopting these mannerisms. But yeah, they would watch surf videos on YouTube and then kind of translate it into their own surf culture over there.

abl: Did you get an idea of what surfing means to their communities there?

mf: I mean it’s become a bit of like a tourist attraction in Senegal. Tourists from France and different places go there to the surf now, and a lot of the surfers have become surfing instructors, so that’s become a source of income for them. Some of them are really good and are able to travel internationally and compete. So it’s definitely developed there.

abl: I guess it’s one of your stories that’s more of a joyful subject matter.

mf: (Laughs) I try to not put things into categories—like this is sad, or this is good. Life is just a multitude of things you know, and I think sometimes it’s good to focus on stories that challenge stereotypes.

abl: I would love to keep talking about challenging stereotypes because it feels like you do that in other parts of your work as well.

mf: Well, I try to do that but I also don’t want that to be my main mission, because I think sometimes people fall into a category really trying to make more of a point. And I’m not trying to make a point. I just want to tell stories that are different, a little bit obscure. I don’t want to be seen as a photographer that’s just on a mission to prove something. I want to show things that I haven’t seen before.

abl: But how do you feel as a black woman in your line of work in this fairly male-dominated industry? You’re definitely challenging stereotypes there. Is that something you think about?

mf: It’s something I’m aware of, but I try not overthink it too much because I think sometimes when you’re thinking too much you can end up putting yourself in a cage. And I think I just want to be seen as a photographer. And I definitely know that that’s not the reality, but I try not to internalize that too much because I think that would just start bothering me a lot. I think the root of the problem, whenever you’re in a minority, is that you’re seen only as that minority. That by itself can be a bit dehumanizing sometimes. I want to try to not put myself in that box, you know? Yes, I’m very proud of who I am very proud of my background, but I just want to be seen as a person that produces good work. I see the industry slowly changing. I’m seeing African photographers coming up and I’m seeing more female photographers emerging. The industry is slowly changing and that’s just wonderful to see.

abl: What tools have been helpful to you in your in your work and your career path?

mf: My biggest tool has been Instagram for sure, 100%. Because Instagram has in a way eliminated the middleman. You used to have to be published in certain outlets in order to get your name out there. With Instagram, it’s become much more democratic. In many ways you become your own outlet, you become your own editor. A lot of the gatekeeping, to a certain extent, has gone away, and you’re able to build your own audience. It’s given a lot of the power back to the photographer.

abl: That’s amazing. But I mean, with Instagram and social media in general, how was that transition going from film to digital?

mf: I was very reluctant to join Instagram. I was late in the game. I didn’t even have an iPhone until very late on. It’s funny because I remember thinking that if I start on Instagram I’m going to be taking much more pictures. And it’s true! I started feeling like I had to produce every day. It became this kind of motivator to consistently produce work.

abl: Even though you’re producing more, is there a change in the quality? Or do you think it’s changing also how you tell stories?

mf: Yeah for sure. It’s more instant and it’s also a very saturated market now because back in the day, photography was a craft and you had to learn how to use the camera and develop film and be in the darkroom. Now you can make a really nice picture with your iPhone and that’s it. So the technology has become so good, any person on the street can take a good picture with very little tools. So it’s become a saturated market. There are some bad aspects to it but overall I think it’s a good thing.

abl: Tell me more about the community of photographers you know. How do you guys inspire or help each other?

mf: Well going back to Instagram, it’s been an amazing tool for us. I’ve discovered very wonderful photographers that otherwise I wouldn’t have been in touch with. I’ve found photographers in Iran, in Africa, in all these different places. It’s helped us build a network. Say you go to Thailand, a photographer will reach out to me and be like, “Hey I’m in Thailand too,” and we’ll meet up on the road.

abl: Of the stories you told, which do you feel are the most important to you?

mf: I think different projects are important for different reasons. It might be a project that I had a very profound experience but I might not have been able to publish it. And then there are projects that had a bigger impact. For example the story I did about synchronized swimming in Jamaica. I was talking to the coach afterward and she was telling me that they were getting so many interview requests and donations and that I created quite a fuss around them and they were getting a lot of great attention. So that’s a wonderful thing. But it’s hard also when you’re working on human rights stories because it’s hard to measure your impact and you hope you’re making a difference and you have to kind of believe that you’re making a difference because otherwise, you’re going to burn out. Sometimes you wish the work had a bigger impact than it does in reality.

abl: You’ve worked with the Malala Foundation for quite a bit now right?

mf: Yeah, a few years now. Malala puts a lot of focus on education for girls, especially in refugee camps. The first year we went to Lebanon and Jordan to give attention to the Syrian refugee crisis that was going on. Two years ago we went to Dadaab refugee camp in Kenya to give attention to a lot of the Somali refugees that were there. And last year we went to Mosul, Iraq to turn the lens on the refugees that were coming out of Mosul.

The girls, especially the young girls, are vulnerable in these camps. They are with their family but protection is not that great and you have a concentrated amount of people in tents. Safety and sanitation, all these things are big issues there. Also schooling is a huge issue.

abl: Because it’s non-existent?

mf: It depends on where you are, but in Lebanon it’s been a huge issue because I think they are hosting about one million refugees in Syria and the population of Lebanon itself is 4 million people. So how do you absorb that many children into the school system? You can’t even if you wanted to. So these people they’ve been living there for seven or eight years now. And that’s a whole generation of people who are growing up with no education.

abl: A lot of the work you do has been global and mostly outside of the US. But I do remember some work you did when you went to Selma. How was that?

mf: I did a story for the New York Times about the march from Selma to Montgomery, and it was for the 50th anniversary. They sent me there to find people who were on the bridge that day when they were attacked by the police and to retell their stories about what happened.

abl: How was that experience? Because you didn’t grow up in the US, but coming here and knowing the history…

mf: What struck me the most was just how optimistic that generation is. Because they suffered from very bad oppression but still have this inner strength that I just really admired. And they really inspired me. I think about things in my life that I find challenging, and just seeing people dealing with those things with such grace, I find it very inspiring.

I think in America, for a long time, a lot of these narratives were suppressed. But I think that’s going to change. Newsrooms are slowly but surely changing and I think it’s something everyone needs to be reminded of from time to time—to see things from different points of view and to step out of your world. As a journalist, you’re supposed to step into other people’s realities than your own and not just staying in your own little circle. I think that’s something important for everyone.■