bob melet: How should we begin?

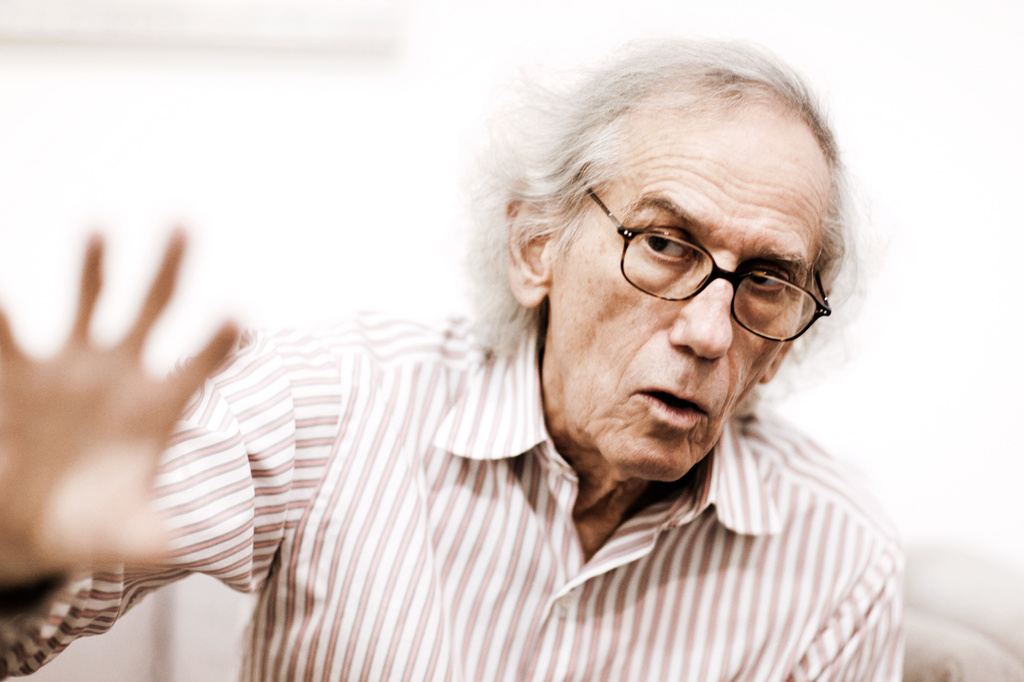

christo: First, I will not answer questions about politics, religion or other artists. I only speak about myself. I’ve been here in New York since September of 1964. My late wife, Jeanne-Claude, and I first rented out the two top floors then and we bought the building in 1973. Now all of the building, from the top floor to the basement, is used for our art.

bm: My father, who collects art and books, came to visit you. It must have been right after you moved here. Harry Abrams liked my father very much and my father looked up to him like a mentor. At that time, he had a little bit of money that he had saved. He said, “Mr. Abrams, I want to buy some art. Who should I buy? I have a little bit of money.” He said: “You must meet Christo and Jeanne-Claude.” He gave the phone number for this apartment, and my father called in the morning. Jeanne-Claude answered and she said, “No one calls before 12:00.” He felt so bad.

c: We have a system. When we do business with Europe, it’s in the morning. Jeanne-Claude would wake up at five in the morning, work for three hours when it was early morning in Europe, and then go back to sleep until noon or so. This is why we don’t take calls before then. The time is reserved for

Europe—or sleep—to this day.

bm: Well, my father had the courage to call back later that day. This time, he disguised his voice maybe a little bit. Of course, Jeanne-Claude was very nice and receptive. So he came and met you. At that time I was just a very little boy. He bought one of your “Store Fronts” and one of the “Wrapped Statues.” I grew up my whole life with these pieces in my home. I’ve always been a very big fan.

c: This is work I did in ‘63 or ‘64. He was in publishing, your father?

The Gates, New York City, 2005.

Running Fence, California, 1976.

bm: He was in the women’s clothing business in Detroit, Michigan. He would come to an apartment he had here in New York for buying trips. He would then go and buy books. So I feel I’ve come full circle here meeting you. How many books have you made over the years?

c: We’ve done many. With Harry Abrams we did big projects like, “Valley Curtain,” “The Running Fence,” “The Islands,” and “The Pont Neuf.” He also did a general book on all of our work in the late ’60s or early ’70s.

bm: Do you still see private buyers like that?

c: Everyone who I see comes here. Very few works of mine are in galleries. Most of the works are immediately sold to collectors, dealers, corporations and museums.

bm: Is it difficult to obtain permission for your projects?

c: It’s a very complex thing. In the last fifty years, we have realized 22 projects and we failed to get permission for 37. Sometimes, we’ll get a refusal and we will decide to move on from the project. Sometimes we’ll have two or three refusals. “The Pont Neuf Wrapped,” for instance, was twice refused,

and “The Gates,” was once, but we still were able to figure them out eventually. I proposed to wrap the Reichstag in 1971 and it was only approved in 1995 after three refusals. The idea to wrap the Pont Neuf was in ‘75, and was realized only in 1985.

bm: How did you and Jeanne-Claude go about choosing your projects?

c: There were two ways of deciding. We had to choose between the city and the countryside. For the island project, we were looking for an aesthetically pleasing shape. There are many things that we took into consideration when deciding what to wrap. Rural areas are different because there is never the scale like in the city with the man-made structures.

bm: Did you two ever go to your installations without people knowing it was you, just hear and see what people were doing?

Wrapped Package, 1963.

c: That is the most difficult part. I don’t really listen to people. Any interpretation of a project, when it is realized, is legitimate. We are not writers. There are many, many different ideas about our projects that we aren’t aware of. “The Umbrellas” were twenty feet tall, 29 feet in diameter, 640 square feet. They were like roofs without the walls. We placed 1,340 all over the towns, villages and countryside of Japan. They were beside post offices, churches, temples and gas stations. In California it was the same thing. The poles were nine inches around. There was a huge seven-by-seven foot base. People in California would come and have picnics with blankets on the platform bases. In Japan, it was a little different. They would remove their shoes before stepping onto the platform, because in Japan you do not walk at home with your shoes on. These interpretations of our art—they are all legitimate. Our pieces of art are as big as the town’s imagination. This is why we do these projects, because they absorb a variety of interpretations.

bm: The process, from beginning to end, must become easier with each project.

c: It’s very important that we never do the same thing twice. We would never wrap another island or build more umbrellas. Each of our projects has created a unique image. We can never repeat that image. There is a fundamental complexity and difficulty in getting permission for each plan. Everything in the world is owned by somebody—there is not one square meter that isn’t owned by someone. Our principle objective is to get permission to rent those spaces. We now know how to plan a fence and a gate, but the next thing we will not know how to do.

bm: You must get help though, right?

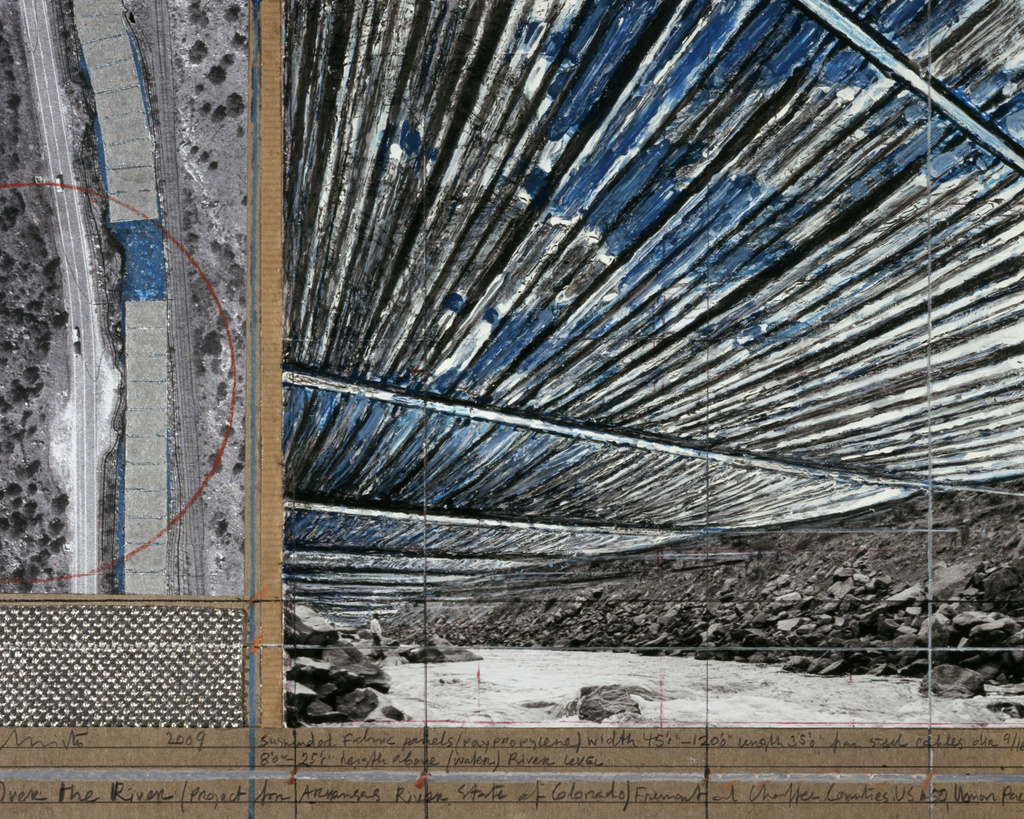

c: We seek out a huge number of resourceful, professional people to charter and help us get permission. There are two stages for each project. During the first, the work only exists in drawings and sketches. They are simple at first, and then they change and evolve. This is the most difficult period because we must wait a long time for the project to be realized. This is the entire process of our work. Our works have a lot of similarity to architecture and sculpture. For example, when we wrapped the Reichstag, the New York Times did not send the art critic, they sent the architectural critic. The mechanics to get permission is very similar to urban planning and architecture. The U.S. government owns almost the entire 42 miles in Arkansas which we used for the “Over the River” project. We had to prepare an application for permission to rent the land just as anyone who wanted to build a bridge or a road would have to. The 2,029-page proposal book cost us 1.5 million dollars.

bm: I think you should wrap that book.

c: Indeed. After we made it, the government said that we needed to hire a special company to review our book. So, we paid them too for their additional comments and writing. 1,686 pages later, the government allowed us to do the project. We worked for nineteen years on that. We spent about fourteen million dollars. The most important thing for any artist’s work is to make people think. Do they like it? Do they dislike it? Indifference is the most terrible thing for any artist. With all of our projects, years before they exist, thousands of people think and write about how they will be awful or beautiful. There are few other artists who are making people think about their work before it even exists. Our projects create a very different kind of participation. They aren’t in museums. People must come to a new venue.

bm: When you do so many regional works for each study, do you focus on one work at a time?

c: No, I do layouts of several types at a time. For 25 years, I did collages and scale drawings for the wrapping of the Reichstag. There are photographs and films about it. Architectural art is all about illustration. When you see a film about the Vietnam War, no one is actually being killed or wounded. With all of our projects, during the time when the project exists for a precious few days, it is the real thing. They consist of real things. It’s about the wind, the water and the traffic in the skyway, the bridges. It’s not a photograph about the things or a piece of writing about something. It is the real thing. I don’t like to work on a computer. I don’t understand anything going on on the screen. I don’t like to speak on the telephone. I want the real cold, the real hot and the real wind. All of that is part of the dynamic of each project.

bm: When you create projects that last for two weeks, I get to go to Central Park and experience it. But the idea is that I’ll carry that experience with me my whole life, right?

c: Yes! It is a very open dimension. There are all different experiences that one could have. I cannot even speculate how many.

bm: Is that open-ness part of what motivates your work?

c: We do these projects for ourselves and our friends. If others enjoy them, then that’s a bonus. I lived until the age of 21 in a communist country. I escaped to the West in 1957, during the Cold War. I was a young student of the arts. I escaped to do art and to satisfy my freedom with art. Our art pieces are visually stimulating—they have nothing else. They are totally useless. They are totally irresponsible and irrational. The world can live without “Running Fence.” When they are overly explicit messages in art, I worry about propaganda. I left my communist country to not do propaganda—whether commercial, governmental or religious. Many critics say I am an artistic chauvinist. Well, of course I am an artist chauvinist. I live only to do my art.

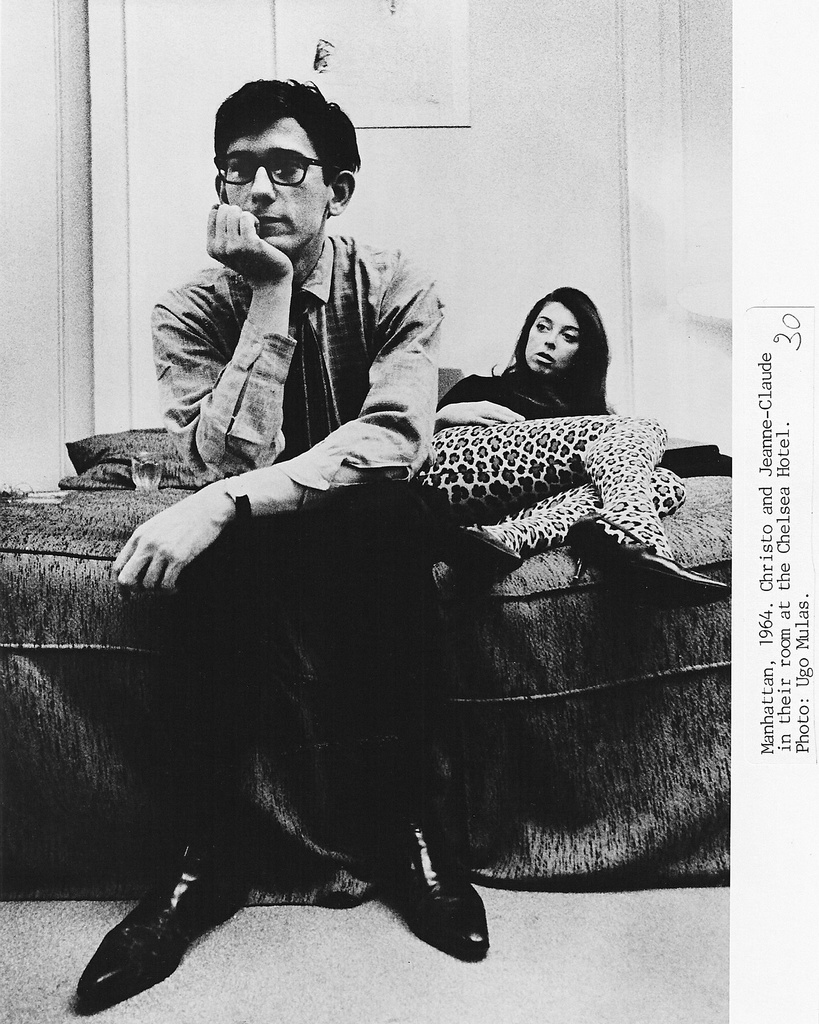

Christo and Jeanne-Claude at the Chelsea Hotel, 1964.

bm: I’m an artist who works in a different medium. I use textiles and I deal in antiques and textiles. As someone who loves textiles, and tactile things, how do you choose the actual fabrics and the colors and the cables?

c: All of our projects use textiles. The fiber of our typical textile is artificial, and comes from petroleum—it’s nylon or polypropylene. We cannot use natural fibers like cotton because it would not resist the erosion. Each time, we try to find a texture that satisfies our needs. In 1980, we had the idea to surround seven islands with six and half million square feet of fabric. We were trying to find a company that would fabricate our material, preferably on the East Coast. This was the largest amount of textile we’d ever used for a project. It also needed to float. The only artificial fiber that will have gravity less than the gravity of the water is polypropylene. It would barely float, though, so we had to hire a company to help us research how to do this.

bm: How did you decide on the color?

c: We decided to use a strong pink fabric. For all of our projects, we find a secret place, without people knowing, without engineers and advisors, to construct several one-to-one scale sections of the project. We assemble this section in the real dimensions to choose how the fabric moves in the wind, how it looks from far away, etc.

bm: So, where did you go?

c: The project was in Biscayne Bay. Our friends have a house in Key Largo. We did a life-size stage there. The fabric was attached to the beach area of the islands and floated 220 feet out on the surface of the water, ending with octagonal-shaped boons. We created a piece of the pie. Within 24 hours, that pink fabric had become white from the sun and the salt water. So, we knew we needed the fabric to float but also to resist fading. There was a small company in Germany who said they could do it. Since 1980, all of our fabric has been done in Germany. When the fabric was being woven, they injected millions of microscopic bubbles of air into the fibers. They solved the problem of gravity, but then another problem arose. The fabric was very heavy and we needed some 800-foot piece sections to wrap around the islands. We needed a fabric that was very widely woven. Ours was 17 feet wide. The next problem is how to sew this fabric in 800-foot sections. There was no parachute company or military that could do that. So we found a blimp hangar in Miami, and professionals to sew it all up—we had our own factory, basically.

The Mastaba

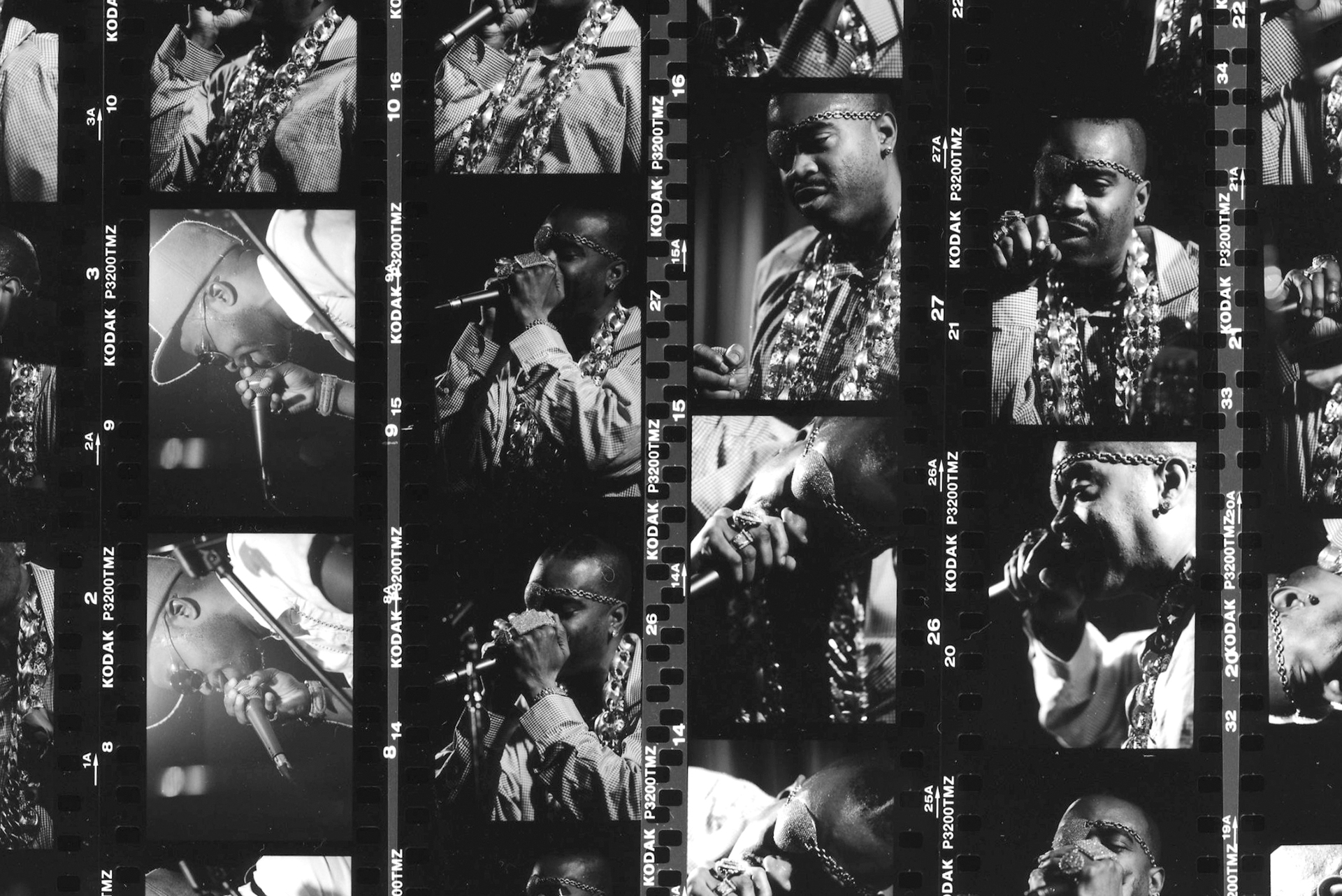

Over the River

bm: Amazing.

c: The color pink is not the work of art. It’s about the color of the tropic vegetation, the different blues and greens in Biscayne Bay, the luxury apartments nearby, all of the boats and activity—that, taken together, is the work of art. The project is not done with tents or fabric; it’s done with all of these things.

bm: Do you ever trade artworks with other artists?

c: Jeanne-Claude and myself lived in Paris between ‘58 and ‘64. We exhibited during that time in many countries in the West, and exchanged work with different artists. I loved very much the great Dutch architect, Rietveld. Mr. Rietveld gave me a package and it was an original drawing from 1919! We have some Warhol, Arman and Miró, but we are not really collectors. We are very close with the American artist, Steinberg. We have many of his pieces.

bm: You met Jeanne-Claude by painting her mother? Where is that painting now?

c: When I first left Bulgaria, to make money I did portraits of the ladies and children of well-to-do families. I would sign the works with my first name, Christo, a common Bulgarian name. I was a political refugee and getting to Paris was difficult. I moved from Vienna to Geneva because it holds the headquarters of the refugee program of the United Nations, so they could help me to pass through the border to France. I lived in Geneva for half a year. Then, I went to Paris and after a few months there I met Jeanne-Claude. I went to her home to do portraits of her and her parents. The portrait of her is now owned by a man in La Jolla, California. When I moved here, I had to sell my work of course. We met many collectors. At that time I wrapped a portrait of Horace Soloman and a portrait of Holly Soloman.

bm: Do you get a desire to wrap more objects these days?

c: No. First of all, many of these projects take a long time to build because of the permission process. We never work on just one project. In 1992, when we had the idea for “Over the River,” we had just finished the “Umbrellas.” In ‘91, when the “Umbrellas” were standing in Japan and California, we finally received a letter about the Reichstag project from the President of the Parliament in Germany. Our proposal had lasted through six Speakers of the House. Finally this President, Rita Süssmuth, who had just been elected—we had never met. We never knew her. She was congratulating us for the “Umbrellas.” She asked us to come to Germany to start petitioning again for the Reichstag. We were very excited because she was a real person, not an art collector but a professor and politician. Between ‘92 and ‘94, we spent 180 days in the very small and boring city of Bern. Jeanne-Claude was saying that she’d had enough of German politicians and cities. “Let’s do a project in the United States,” she said. When the German politicians were on holiday in August, Jeanne-Claude, myself and our friends, we traveled 15,000 miles around the United States. We went from Idaho to Wyoming, Colorado to New Mexico. We came to six different ideas. In 1994, we got permission for the wrapping of the Reichstag. We stopped everything else immediately to work on it. The moment that we have permission, we focus only on the one project.

Wrapped Reichstag, Berlin, 1995.

The Pont Neuf Wrapped, Paris, 1985.

bm: Was this around the time you were planning the Gates project?

c: Yes. We were eager to do the Gates, but Giuliani hated that project. During the Clinton administration, in ’98 and ’99, we had a great chance because we knew that we needed permission from Washington. The Secretary of Interior, formerly Governor of New Mexico, Bruce Barbee, was very fond of our work. He helped move us through the very complex permitting process. Then, Bush was elected. Thankfully, in 2001 a friend of ours for over 20 years was elected mayor of New York. We met Mr. Bloomberg many years prior, when we were first refused for the Gates. We had asked him to help us because he was a member of the Central Park conservancy in the ’70s. We asked him to try to convince some other members about the project, but he was not successful. We became very close friends. He wasn’t a collector, but he was very interested in how we built our projects. When he was elected, right away we stopped working on other projects and we finished the Gates. A project that we started in 1979. It took almost 30 years!

bm: How can people help you today?

c: Only to buy art! These projects cost millions and millions of dollars of our own money, which we earn through these sales. Now, I don’t know how familiar you are with the art world, but people in this world are notoriously slow payers. They do not pay, or they often pay in installments. You need to call them. We cannot say to our workers on Friday: “We cannot pay you because Mr. Smith, who bought a piece, didn’t pay for the work.” What we do, because we have so many works of art … we work with certain banks that believe in our art, and give us a line of credit when needed.

bm: So people can help you by buying your work.

c: When people buy works of our art, they buy goods and they can sell them. This is why I was very adamant in saying that we don’t raise money. We didn’t, and don’t. We sell goods. When I was in my early twenties, of course I wanted to have a gallery that represented me, but nobody was interested in selling my pieces. Now behind me, that package is five million dollars. Those two bottles over there are worth four million dollars. The least expensive work, that 8.5 x 11-inch sketch over there, is fifty thousand dollars.

When Bloomberg was elected, right away we stopped working on other project and we finished the Gates. A project that we started in 1979. It took almost 30 years!

bm: When you and Jeanne-Claude spoke to one another, which language did you use?

c: We spoke in French, but the technical parts we spoke in English. I don’t know the names in French.

bm: What do you do with the materials after a piece is realized?

c: Since the beginning, I’ve put aside many original works from the early sketches and drawings. I do not do drawings when the project is realized. I do them all before. After the project is exhibited and we remove the pieces, we keep the poles, the hooks, the documents, etc. Each of our large projects has had their own large documentation exhibit. There’s nothing for sale at them. But we often use these exhibitions to sensitize a new place when we’d like to get permission. For example, when we tried to get permission for the Reichstag project, we visited the Parliament of Bonn at that time, and exhibited the Pont Neuf project at a museum there. We wanted to explain to the German politicians how that project was realized. Now we’re working to sell the Reichstag exhibition to a foundation in Germany very much like the Smithsonian.

bm: Were you happy when the snow first fell in Central Park during “The Gates” installation?

c: We knew there would be snow. We hoped there would be snow. To accomplish “The Gates,” we did two life-sized tests. The first was done in the early ’80s, and the other in 2002 after we got permission. Our chief engineer and director of the project has a house in the Cascade Mountains. He has a big open ground there and we set up eighteen gates there in all different colors. We wanted to see how they would hold up in the wind, rain and snow. We chose the poles and colors and everything based on how they worked with the elements in Washington. All of our designs are made for a particular season of the year. “The Gates” project was a winter one. We didn’t want leaves on the trees obstructing the view. “Surrounded Islands” was the spring project before the hurricanes came later in the year.

bm: What do you have planned that we may get to see in the near future?

c: “Over The River” is 42 miles long running along the Arkansas River and the Eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains in Colorado. We chose the Arkansas River for many reasons. One of the principal reasons is that it is the most rafted city in the United States. They have 300,000 rafters in the summertime. To plan for this project we set up six miles of fabric at eight different locations along the river. We learned that the fabric must be a minimum of 96 inches from the water There are many supporters along those 42 miles, but there are also many people against us. We want to have it for two weeks in August so as many rafters as possible will see it.

Wrapped trees, Richan, Switzerland, 1998.

Valley Curtain, Colorado, 1972.

bm: What will the experience be like for people on the river?

c: There are two ways to see the project. When looking from the road above, you can view the silver-colored fabric moving in the wind. We know how they look because in ‘98 we did three large-scale tests. Getting permission for this project from the federal government and from local governments in Colorado has taken some time. Fortunately, the former mayor of Denver, John Hickenlooper, became the Governor of Colorado. He’s a big supporter of our work. Through the years we have made great progress but there are always groups of people trying to stop us.

bm: What do they have against it?

c: Their main concern is that there will be too many tourists and traffic. They chose where they live because it is quiet. And even for two weeks, they do not want to put up with the nuisance. By the way, you may be too young to remember this, but Colorado is very stubborn. The winter Olympics was refused by the state of Colorado and told to go to Utah. Once we get permission there are two stages. We must manufacture the cables and poles and fabrics. We must take into consideration the 5,800’ altitude. We must only work in the spring and summer to construct the project as the snow and frozen ground will be too difficult to work with otherwise. To realize the project we need about 28 months. We need the two years to install the 9,000 anchors. You won’t be able to seem them, but they’ll be in the ground. Only just before the exhibition do we install the cables and everything else. This is much faster. The fabric will take two or three days with the help of thousands of workers.

bm: How is the permission for the “Over the River” project going?

c: After finally getting permission from Fremont County this spring, the opposition started acting. They have no means to go to the courts, as that costs so much. Instead, they went to the University of Colorado and found a professor in the Environmental Clinic. This professor made a class project. He and his students would sue the United States Federal Government in Washington for giving us permission. Now, we are in Federal Court. It’s not the first time. We were sued for “Running Fence” and for “Surrounded Islands.” We always lose about two years in Federal cases because they are very complex and expensive. The project right now is on standby. We don’t know which summer we will exhibit. When everything was going smoothly, we were aiming at the summer of 2014. Now we are unsure

When the Mastaba is realized, it will be the biggest sculpture in the world. Bigger than the Pyramid of Giza.

bm: Can we come and be unskilled help when you do this?

c: You can go to our website and everything is there. For all of our projects we have professional people, but a few months before the exhibition anyone can come and help. We pay such folks minimum wage. You know why?

bm: Because you have to?

c: Jeanne-Claude said there was too much work, and we cannot fire volunteers! People must be paid, and there is the workman’s comp as well. Most of the work is about hooking thousands of very complicated cords.

bm: Are you currently planning any other projects?

c: During the summertime it is usually very quiet and I stay in my studio. Starting next week, I need to travel to Abu Dhabi to work on “The Mastaba” all autumn. It will be very busy.

bm: Tell us about “The Mastaba.”

c: When it is realized, it will be the biggest sculpture in the world—bigger than the Pyramid of Giza. The engineering will be incredible. The project was created in the late ’70s and early ’80s by American engineers. It is like a mosaic, with the structure and the incorporation of 410,000 barrels. Only the proportion is always the same. The vertical wall is 500 feet tall. We commissioned four professors from top engineering schools to independently work on how to build “The Mastaba.” They worked on how much it would cost and how long it would take to build. The biggest problem is that we need to fix a steel frame like a trust. 410,000 barrels. There are ten different colors. We built a scale model in 1979 with the exact position of the colors.

bm: How many barrels will comprise a wall?

c: Each vertical wall will have 110,000 barrels, which I painted myself in 1979. It will be the biggest stairway in the world. Workers will set up the mosaic on the ground and install the barrels like that. Once that is installed, we will start to lift the project from the ground little by little using hydraulics. That will be completed in about four days. It is all paid for by us.

The Umbrellas, Japan, 1991.

Surrounded Islands, Miami, 1983.

bm: Who owns the property?

c: The land that I am building on belongs to the Royal family. They are working with us. Within two square miles there will be an art campus and little museums. The barrels will be built in Germany, and a famous company named BASF will produce the paint. They also make BMW car paint. The colors are very particular. In early October, Taschen will be releasing a large book detailing the project.

bm: One last question and it’s a bit presumptuous, but after we make the magazine with this article in it, would you wrap it?

c: No chance! (laughs)■