alessandro simonetti: Your photographic output has been motivated by a desire to construe the city as a subject. The city is the scene for your work. Your arrival in NYC in the early 2006 marked the beginning of your new approach to photography. How has this line through all of your major projects become such a distinct mark? What role does NYC have in all of this?

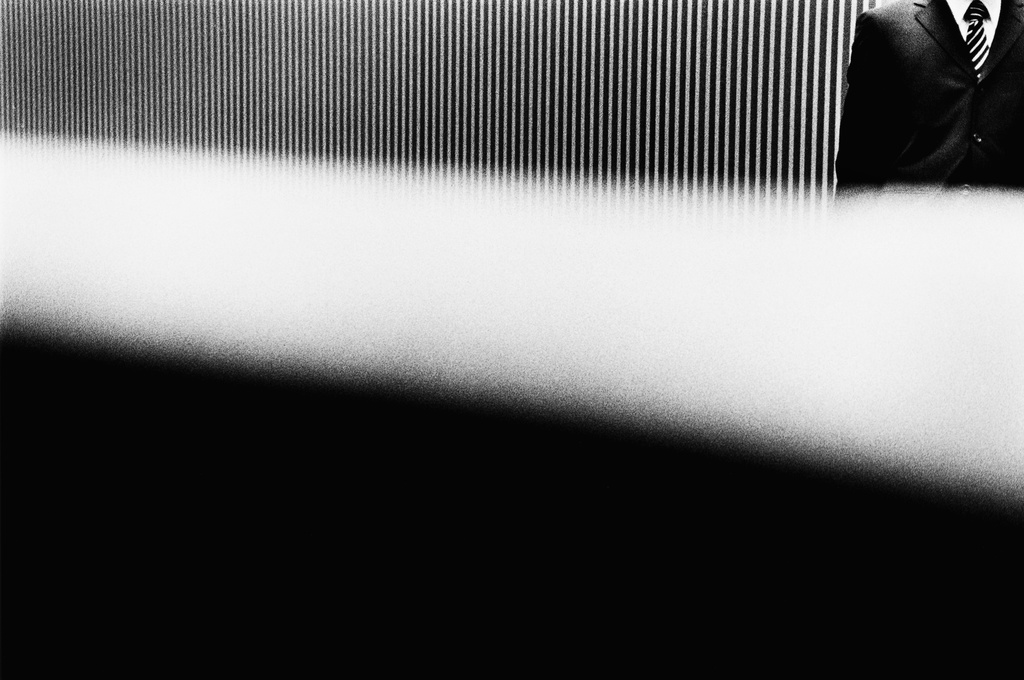

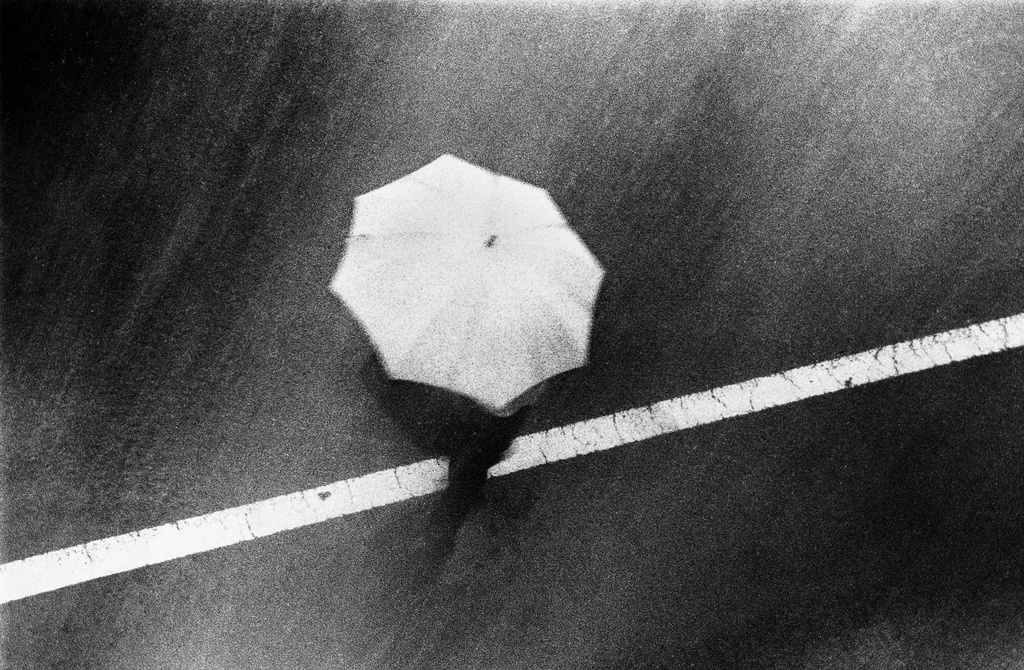

renato d’agostin: I see cities as multi-layered entities where elements interact with each other. Going through them is like floating through someone’s psychology. I had the chance to photograph in Tokyo, Venice, and Shanghai–all cities with very different natures and dynamics. While exploring places, I’m building another dimension, a personal imagery. I am in process of understanding that my work is about the distance between things rather than proximity, silence and suspension rather than noise, imagination rather than representation. I am working on a project in collaboration with Love Child about the intangible qualities of a city that define our sense of place and identity. We have already begun to explore Los Angeles and Istanbul. Mexico City is soon to follow. I arrived in New York and, looking at the city at night through a windshield, I made in pieces as the cab driver pulled out of the parking lot. It was October 2005, and photography was the reason why I came to NYC. It’s the reason why I am still here.

as: Even if I could try and categorize your work as street photography, there is part of that approach that you can’t feel at all in your production. It seems like you extract that feeling of epic presence that most street photographers have. What is happening in your head when you are out shooting in the street?

rd: I see a photograph as perception of reality. Then, most of the time, I manipulate what I see–including or excluding elements from the frame as I shoot, looking for points of intersection and point of contradiction. I use a long lens on my camera so as to not interfere with the world, decontextualizing subjects from the situations they live in and making them part of the imagery I am building. I believe that the subject grows inside the photographer, rather than the photographer looking for it. Then elements from reality get distilled in order to express it. I guess that all of this doesn’t strictly belong to classic street photography, but I do shoot on the street. Composition is an alphabet of the language I’m exploring. Andrei Tarkovsky said, “If the world were perfect, man wouldn’t look for harmony, he would simply live in it. Therefore the artist exists because we live in an ill-designed world.” I like to look for harmony.

as: I am amazed by your fidelity to the medium of the film and your devotion to the darkroom. Do you consider it an important aspect of your process?

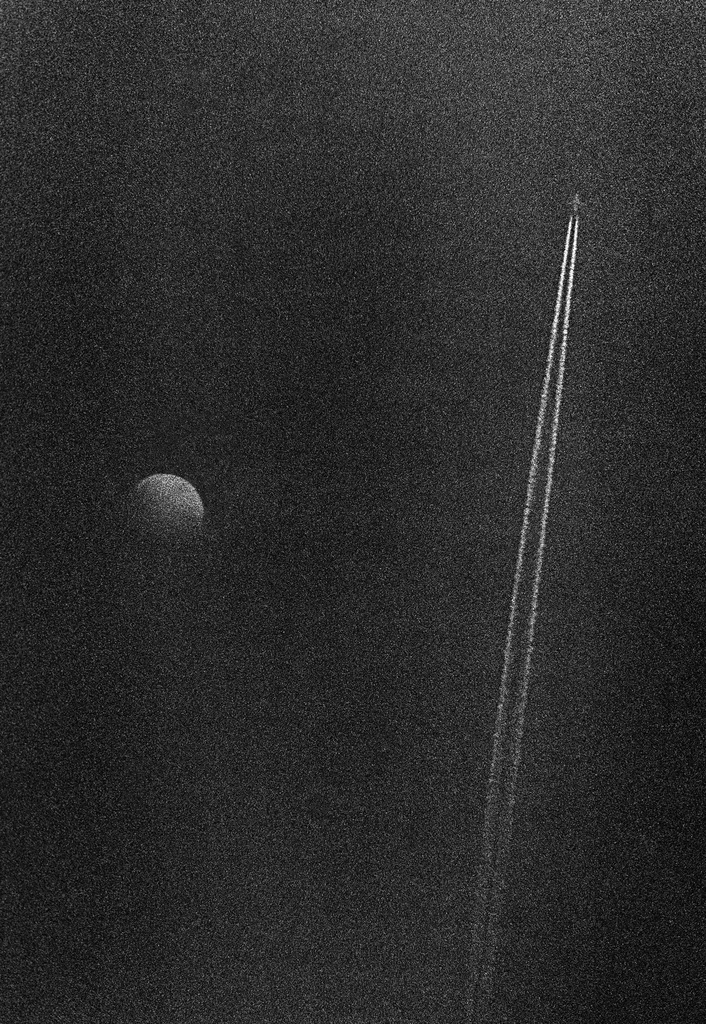

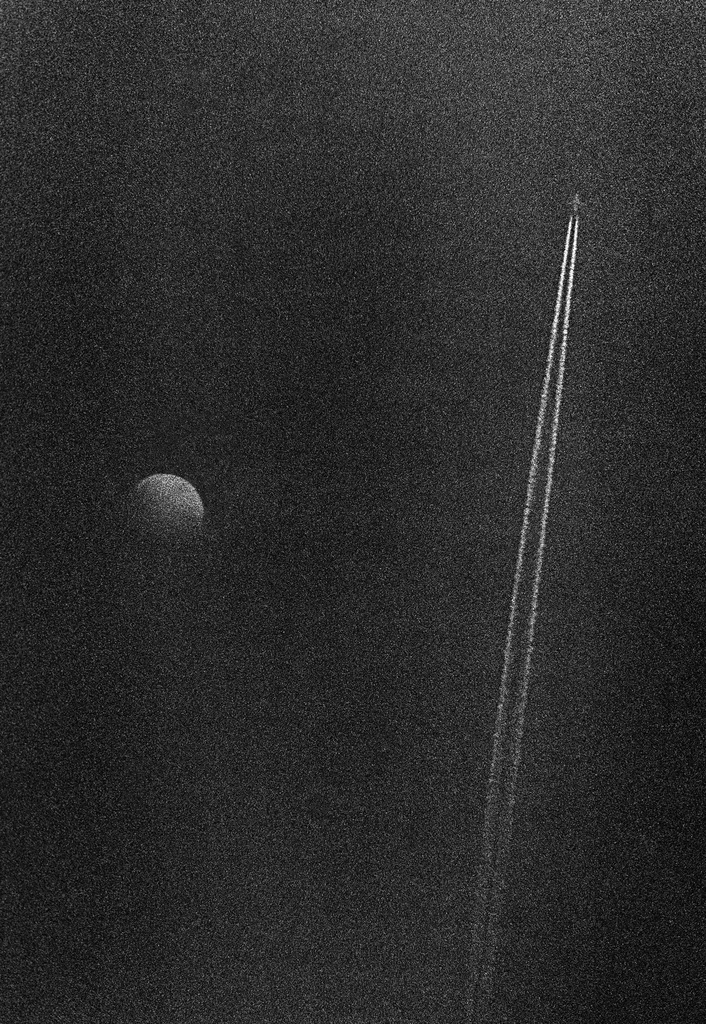

rd: I consider film and the darkroom as the natural extension of light. There is light, and then light again. Somehow, when I’m using a film camera, I feel like I’m photographing what I feel more than what I see. It’s a continuous space between me and the subject. It is also without immediate results that might change my next photograph. Speed assumes a different meaning. The darkroom functions as a place to study my photography and my relation with it. It becomes a meditative place for my work where there is a strong interaction with the materials that make the final print. You can sense a sort of respect for the light.

as: There is something about the way you lay out your images in your publications that reminds me of the feeling of listening to music and looking at architecture. Have you ever considered these elements to be influential in your work?

rd: Music and architecture are recurring elements in my process of making photography. Like in photography, I find they are built on balancing weights and tonalities, space and compression, fullness and emptiness, height and volume. I listen to music while looking at the architecture of life.

as: Why do you make books?

rd: Books don’t change, but exhibitions do. The same book can be seen in one side of the world or in the other, and it will always embody that idea. It will maintain the sequence, the size, and the distance between the viewer’s eyes and the page. An exhibition will always have contingencies based on the space, the curator, the size, and the selection. A book will always protect the artist’s idea through time.

as: I had a chance to see the Etna book and Acrobats, both of them will be released under Nomadic Editions, a publishing company that you created yourself. What’s behind this?

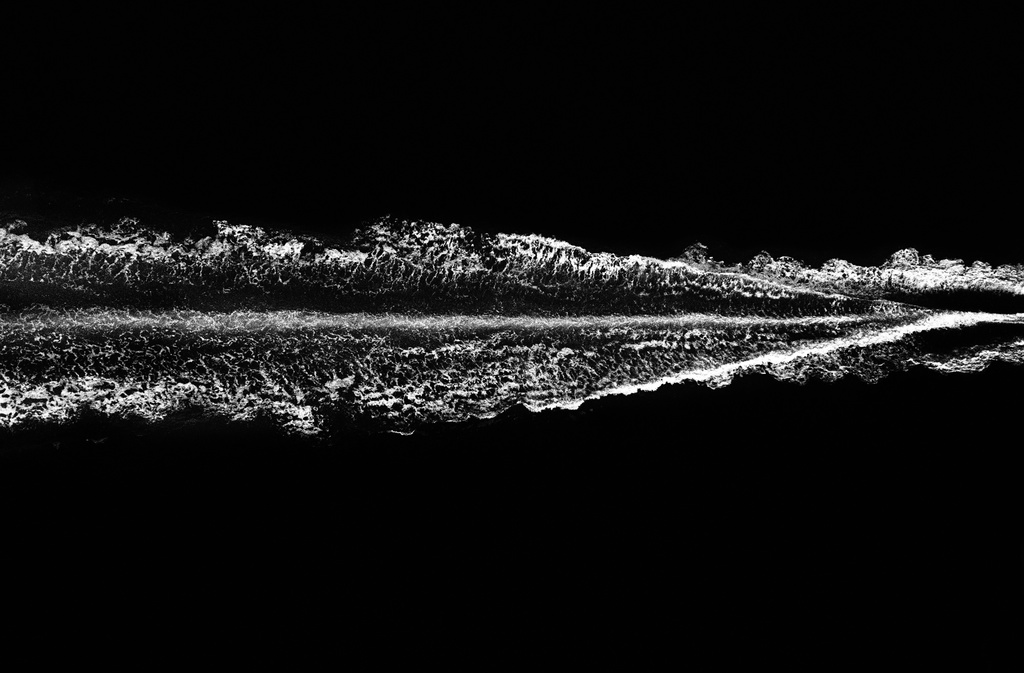

rd: Nomadic Editions will be a series of books on monothematic experiences. I felt the need to detach from the city structures and explore other fields directed by different dynamics. They will be impressions of places shot in an almost touristic approach. It’s from the cities I work on, where each project needs an extended amount of time to go through its layers. The Nomadic Editions series will work on the immediacy of an impression. Etna was an excursion I made in summer 2012, and lasted about two hours. At the acrobatic show of Shanghai, I shot one roll of film in one hour. I’m fascinated with seeing what a first impression can give to my senses.

as: When will you start working on a book about the city of New York?

rd: Whenever I’m brave enough!■