colin tunstall:Where did you grow up?

adrian gaut:Portland, Oregon.

ct:So you grew up in the Northwest and then you moved to New York?

ag:It was maybe a week before 9/11. I came here to work for David LaChapelle, and it was sort of an obscure connection through the university I was at. Paige Powell—who ran Interview at the time—was good friends with David. She had moved to Portland a few years before and started a dog magazine. So she had a dog magazine and she was friends with the president of the college, who I knew from this scholarship thing. So the president of the college was like, “Oh, you should talk to Paige. I’m sure she could set you up with someone in New York for a studio program.” So I did a semester in New York, flew here like September 3rd, and then 9/11 happened. I started with David like the day before.

ct:Did you stop working when 9/11 happened?

ag:No, I called the studio and was like, “So do we have to come in tomorrow?” And they were like, “Yep.”

ct:And you had already been honing your craft in art school by that point.

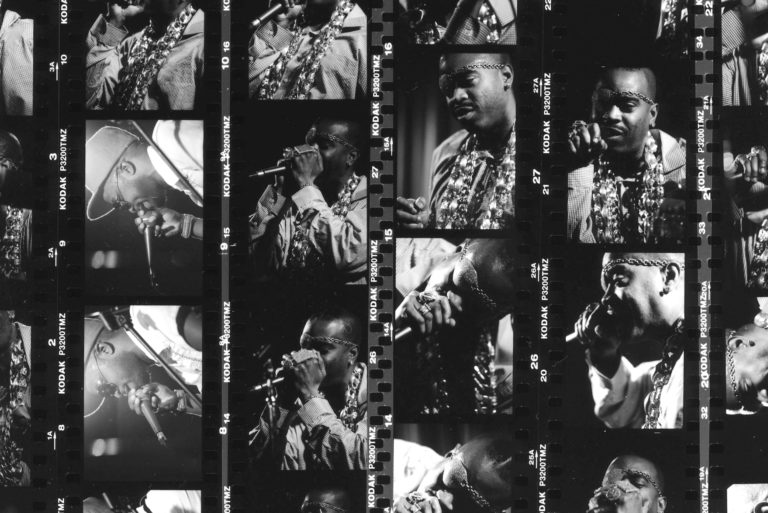

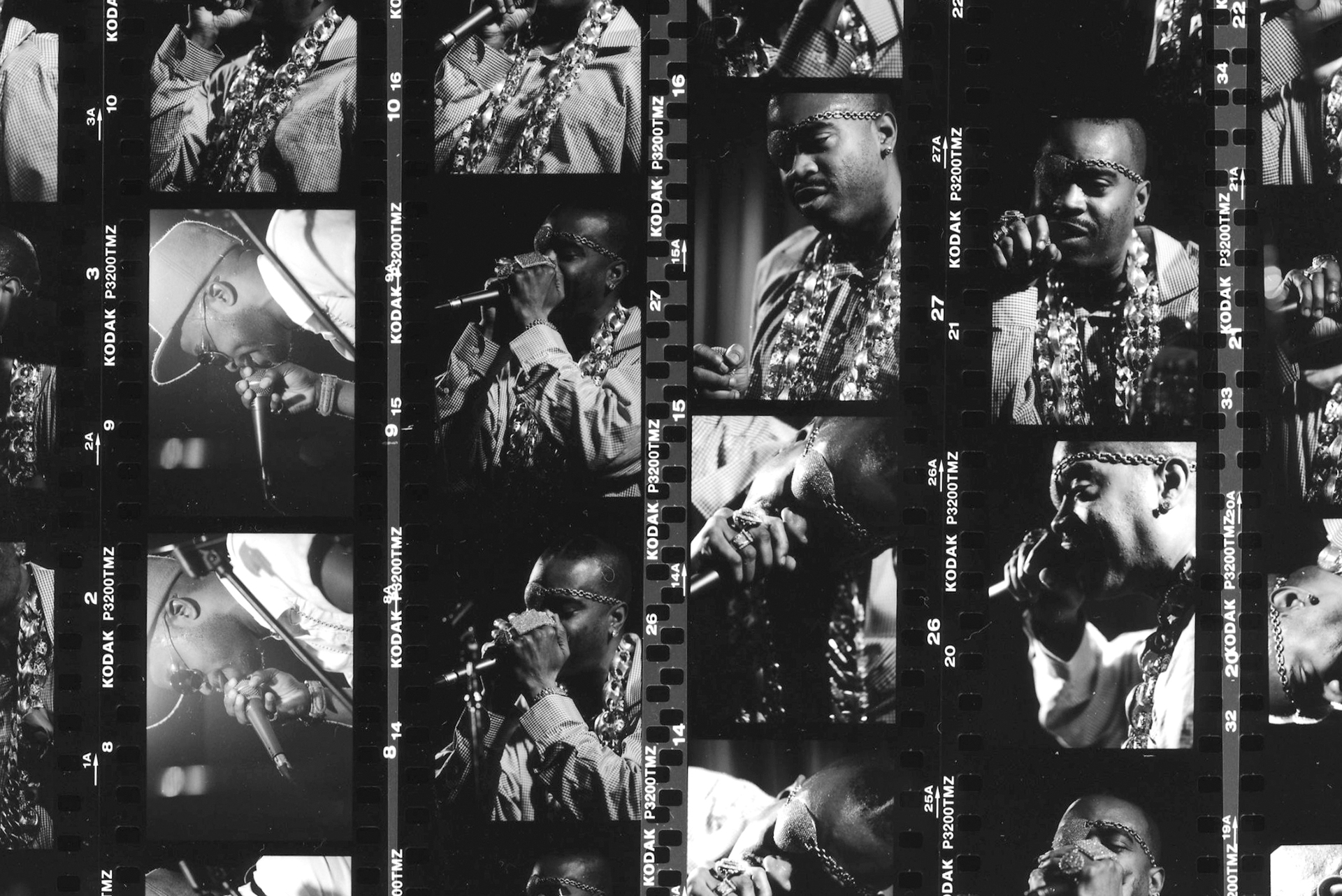

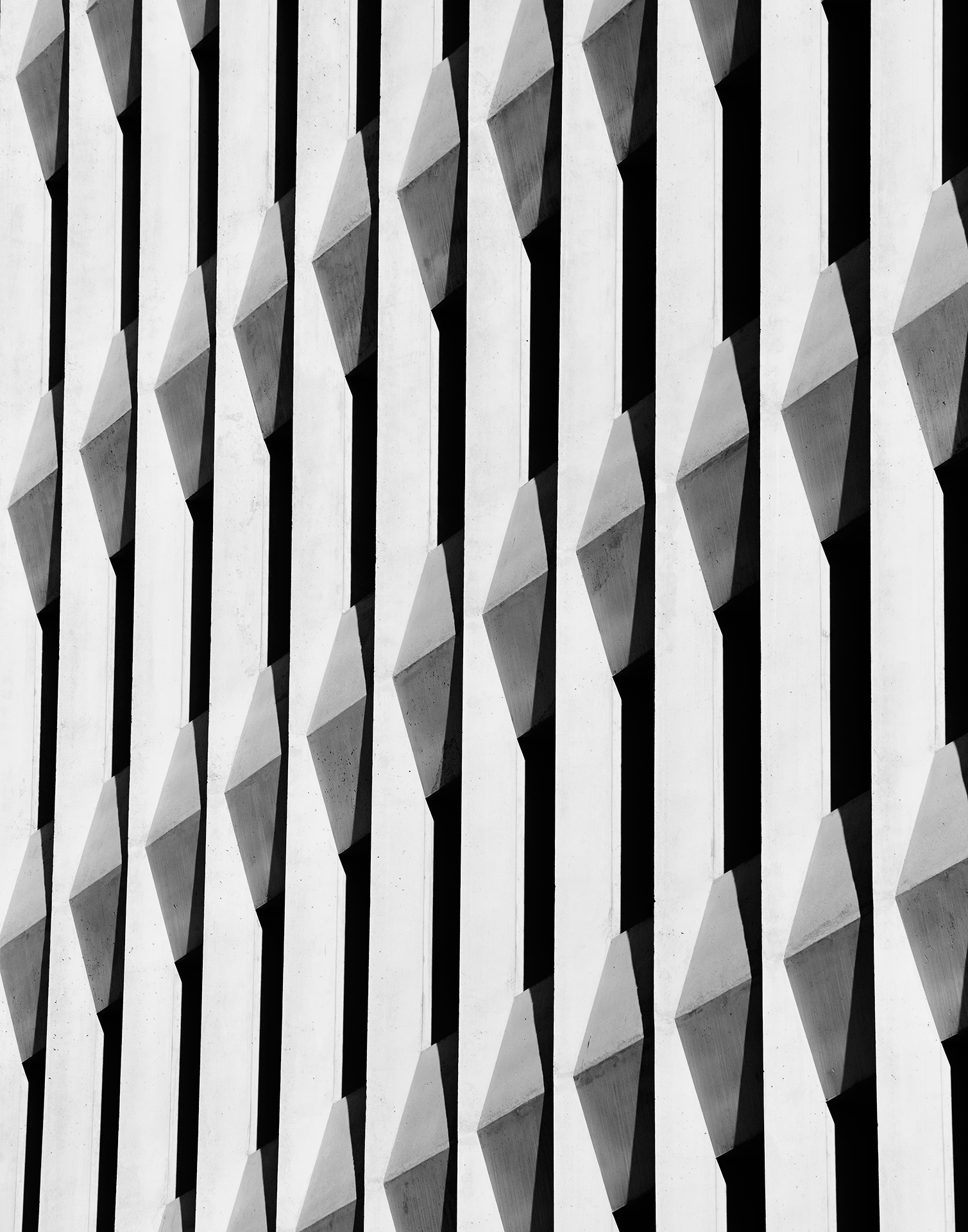

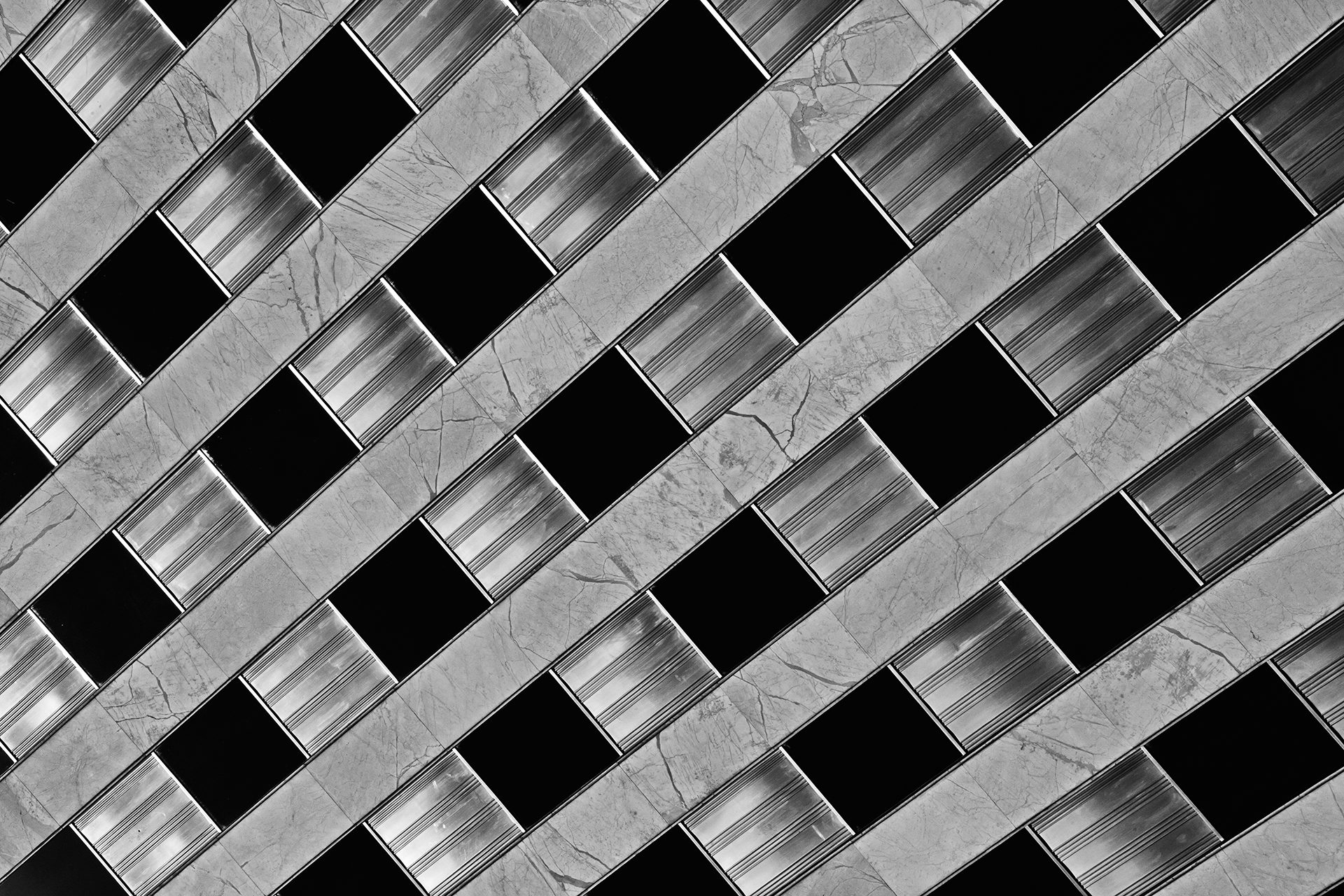

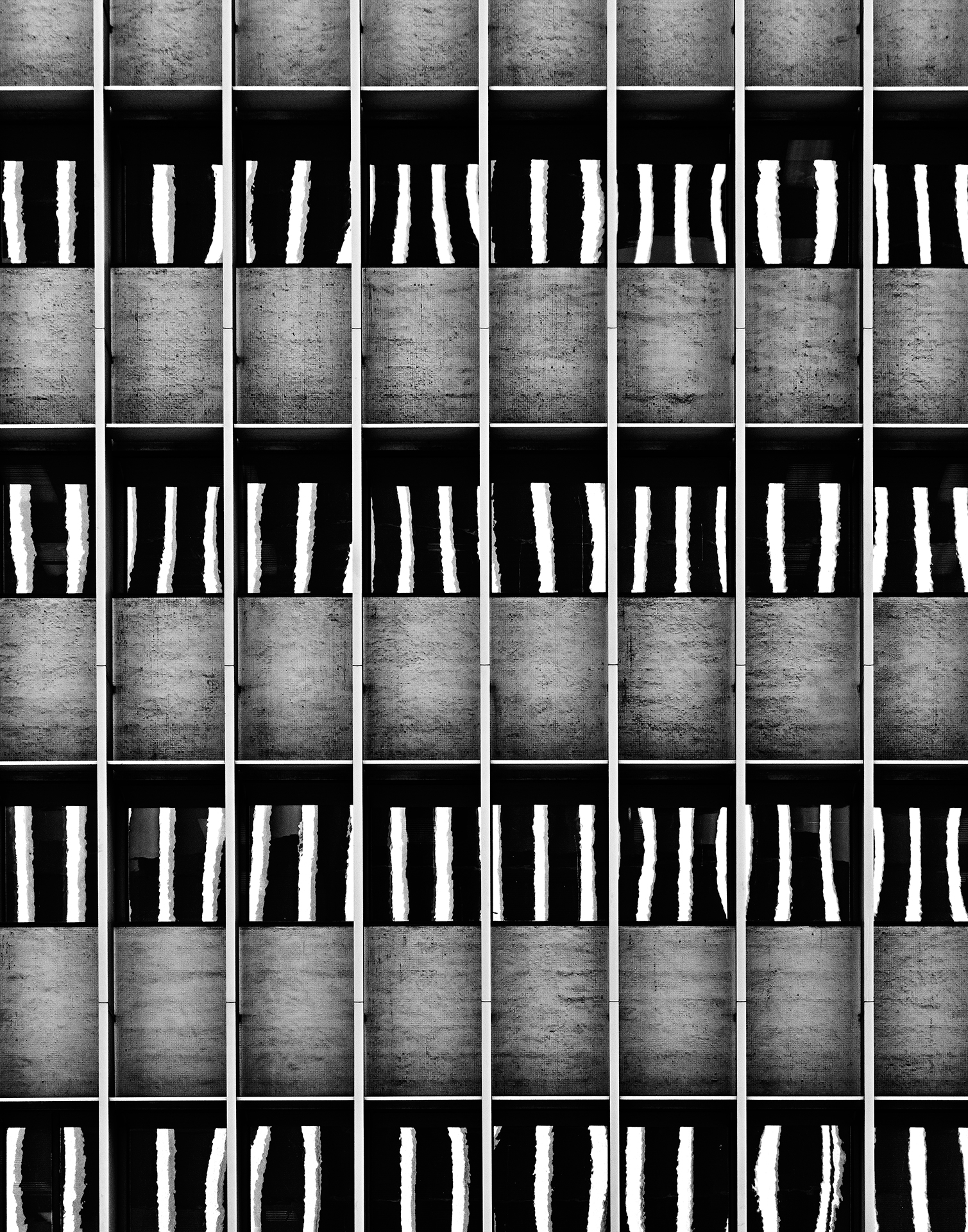

ag:Yeah, I was really into it. I had been shooting stuff since high school. I spent a lot of time in the dark room learning how to print, so I was very serious about the technical side of things. Then I started shooting large format, and that was the first time I was like, “Wow, this is amazing.” I started shooting architecture there, because the neighborhood that I was in and the school that I was in had been gentrified really quickly. There were a lot of these amazing old factory buildings that were being torn down or renovated, so I started photographing those. It was kind of like Bernd and Hilla Becher, or Thomas Struth. I was super into that German kind of cool, non-emotional photography.

ct:So how did your career get started after you finished art school?

ag:Right after I graduated, I spent a year working at a model booking agency and I kind of felt like I needed a change. I started contacting photographers and trying to get assisting gigs, so I called like 300 people. I was also just dead broke. I had just gone to Europe, so I took time off from the agency, and when I came back and I was like, “I got to fucking do something.”

ct:I think the best way to find work is when you’re dead broke.

ag:For sure. I called like 100 people a day, and like 95 said no. But that’s how I started working for Christopher Griffith, who was looking for somebody. When I interviewed with him, we really clicked on some things—Lewis Baltz and Thomas Struth and all that stuff. He was obviously influenced by that stuff when he had done that book States. It was all very neutral, with white backgrounds. He was still shooting all large format black-and-white, and I knew all that stuff from an assistant’s point of view—I could load film, I could expose, I could focus, I could do all that stuff where you need somebody a little bit technical. We sort of hit it off, but then after working for him and being around that for a few months, I really started to miss doing it myself. I kind of felt like I had something to say. So I bought a 4×5 on eBay for like $500, and it was supposed to come with a wide-angle lens and it came with a long lens, and I was like, “Fuck, man. How am I going to shoot architecture?” But I couldn’t afford another lens, and so for the first six months, my first trip to Europe was all on a really long lens. That changed the style of my approach in a way. I started shooting like that, and it felt more original.

ct:But the stuff you’re featuring here isn’t 4×5 large format work.

ag:No, but I spent years shooting large format. Once I signed with Art + Commerce, and sort of got my own career on its feet, I was doing a lot of assignments, and it was all 4×5. So I have boxes and boxes of film.

ct:And you’ve sort of built a niche for yourself over time in the industry.

ag:When I signed with Art + Commerce, my entire portfolio was architecture. That’s what I was doing. I kind of a knew that it wasn’t always the most commercially viable thing, but I always felt like it was better to have something that someone recognizes you for. So I started getting jobs for Wallpaper—I think that was my first commercial assignment—and they hired me to shoot architecture, but after that people would ask me to do cars. A friend of mine was working at an agency, and they were doing a job with Mazda and they asked me to do it. I had worked with Christopher on car stuff before and I sort of knew what the principles of it were. Once I had a little bit of work, Wallpaper then asked me if I wanted to go to the Lamborghini factory. So once I had the first few things, it was a little easier. Wired hired me, then Men’s Vogue was the first magazine that hired me to shoot a car. I shot a Jaguar for them. I did that for years before I ever got a real commercial car job. It’s so funny to think about it now, but in the early days when I really didn’t have the cameras or equipment, I had to fucking track down a camera and lights for every shoot. I take it for granted now, because I have a studio with everything I need, but at that time it was like, “How am I going to make this work?”

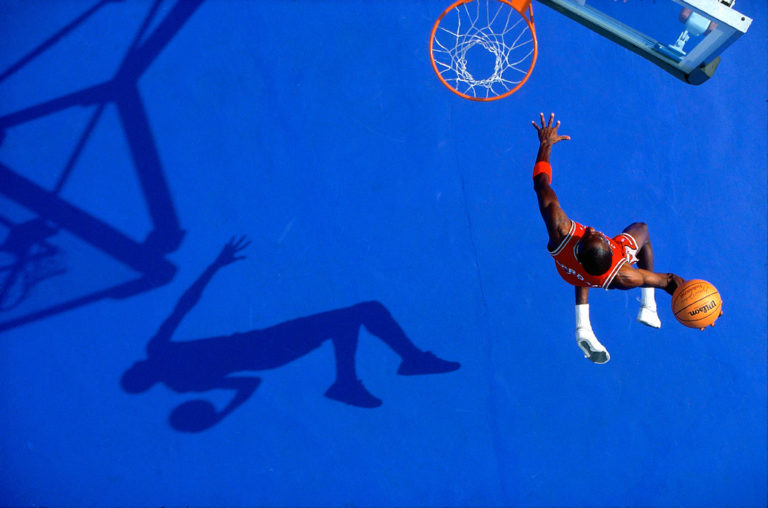

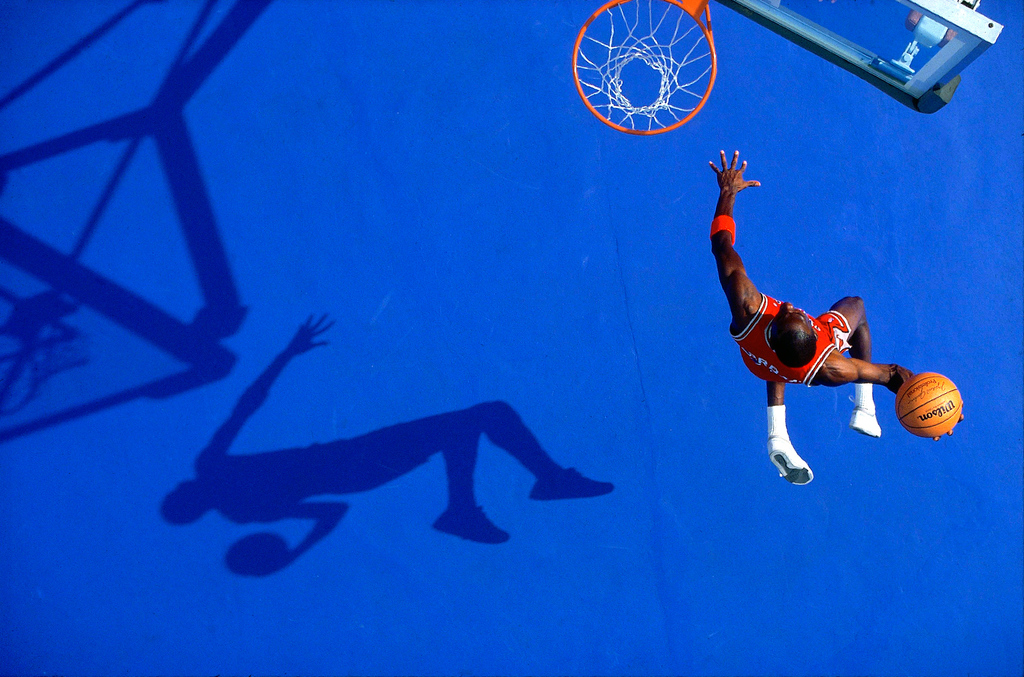

I think that it all comes from the same aesthetic approach. It’s the architecture. It’s trying to find a flattering angle—whether that be a crop or a place to look at it differently. I think with architecture, you’re always forced to shoot up at things, because you can never really get into an ideal position. So, for me, it was always about trying to find a completely alternative approach to something.

ct:There’s so many photographers and so many people shooting everything out there. How do you define yourself and develop your own clientele?

ag:At the end of the day, it comes down to relationships. Being at Art + Commerce was great exposure in terms of introducing me to art buyers and photo editors and people in the business. Those few early relationships were really helpful in terms of setting up the trust level you need when you hire a new photographer. I like to look at it now from the other side of the aisle, where you’re like, “Wow, doing magazines, it’s a lot of trust to give someone an assignment and say, ‘Okay, go do something good.’” You never know. You could have someone who has great personal work, and then when you give them assignments, it doesn’t translate. So I think those first people who started to put a little faith in me were really key. It’s a reputation-based thing. I’ve always tried to approach it from that angle rather than trying to follow a trend. I just like to do a job and make it easy for the client.

ct:So you’ve also been traveling a bunch as well. It seems like that’s a big part of what you do.

ag:Yeah, I started doing that for jobs pretty early. I’ve always excited been excited to travel.

ct:It seems like you’re going to places where people want to go. It’s not even like they’re sending you to bad places.

ag:From early on, I was super hands-on. Even after years of working with Wallpaper and being a lot closer with the photo editors, you’re the easiest person to work with because you just say, “This is where you need to be at this time.” And I always booked everything. Before Airbnb, I would stay at friends’ houses. It was like, “Ok, you want me to show up in Helsinki on the 21st at 9 A.M.? Okay, I can do that. No problem.” In the beginning, I was all about making it easy. And, like I said, it’s all about reputation. You work with one photo editor, and they move to another magazine and say, “Oh, Adrian is great.”

ct:You’ve been able to spend a lot of time between LA and New York for work. What is that like?

ag:It’s great for me. I’m just dumbfounded as to what to do in LA if there’s no waves. At one point I got really obsessed with the idea of having a camper and living out of it.

ct:Tell me about when you first got out there with a surf board.

ag:I had been working out in LA over the years, and it was all about discovering new neighborhoods and surfing in LA. The first time I went, I surfed Seal Beach—that was the only place I could find. I was just trying to get LA wired in terms of where to surf, and that meant a lot of driving around. The architecture in LA is so much more diverse, so much more visually stimulating than in New York, because it’s so much more spread out and visible. In New York, you’re always shooting straight up at things, so it’s really hard.

ct:So you started taking pictures.

ag:Yeah, I started shooting in LA a little bit. Then I was driving to the beach one day down Wilshire, and it’s full of amazing buildings. You go from these sort of crazy downtown skyscrapers to modern stucco stuff to postmodern stuff to glass and steel. There’s this whole range of things, and I thought of it as a sort of conceptual framework for a project. Why not do one street that exemplifies the diversity of LA? New York is such a confined area, so they just knock buildings down and make new ones. Whereas in LA, you just leave it and go a little further, so there’s a lot of stuff there that’s been untouched since the ‘60s.

ct:And that’s all shot with one of your brand new camera equipment?

ag:Yeah, that’s all medium-format digital. As much as I love shooting 4×5, shooting digital is actually more conducive to the way that I work. It’s very fast and loose, and that’s good for walking around a building and reframing on the fly. Working that way is just more fun.

ct:What’s the common thread for you between shooting architecture, shooting in the studio, and shooting on location?

ag:I think that it all comes from the same aesthetic approach. It’s the architecture. It’s trying to find a flattering angle—whether that be a crop or a place to look at it differently. I think with architecture, you’re always forced to shoot up at things, because you can never really get into an ideal position. So, for me, it was always about trying to find a completely alternative approach to something. I think that also translates well to cars.

ct:Do you shoot multiple-exposure?

ag:A typical car ad will have about five exposures—maybe it’s one for the headlights, one for the bright parts of the car. The way I shoot cars now is that we’ll bring lights in really close to get a high contrast. Then you shoot another plate with no lights so you can have the background and the location.

ct:It almost looks like some of the Wilshire stuff was shot then pieced together.

ag:No, that’s all straight from camera basically. Aside from some manipulation with the curves, there are no alterations done on the structural stuff. My approach to photography in general is to do the least amount of modification as possible. I don’t shoot lights a lot, because sometimes you can make a dramatic, beautiful picture without them.

ct:Does your work now revolve around being taken to surf destinations?

ag:I will say in all honestly that I have rescheduled jobs based on long-term surf reports. The great thing about California, too, is that you have the ability to predict the swell a week out. So if I see that a swell is hitting Friday, and I can shoot any time of the week, of course I’m going to go with Thursday. For example, I shot a car in LA for the Wall Street Journal, and it’s a good shoot, but it’s not one make a ton of money from. But I did happen to notice that there was a solid south swell hitting, so I figured I’d fly out for the day, do it in the morning, surf all afternoon, and come back, and then it’s worthwhile.■