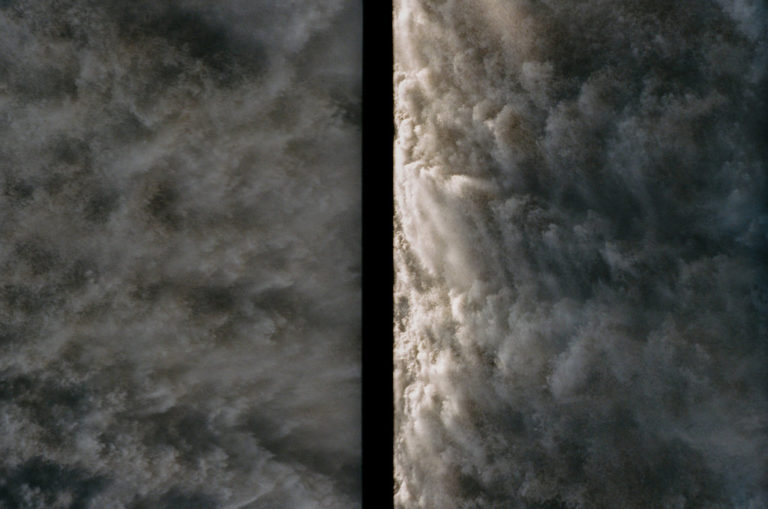

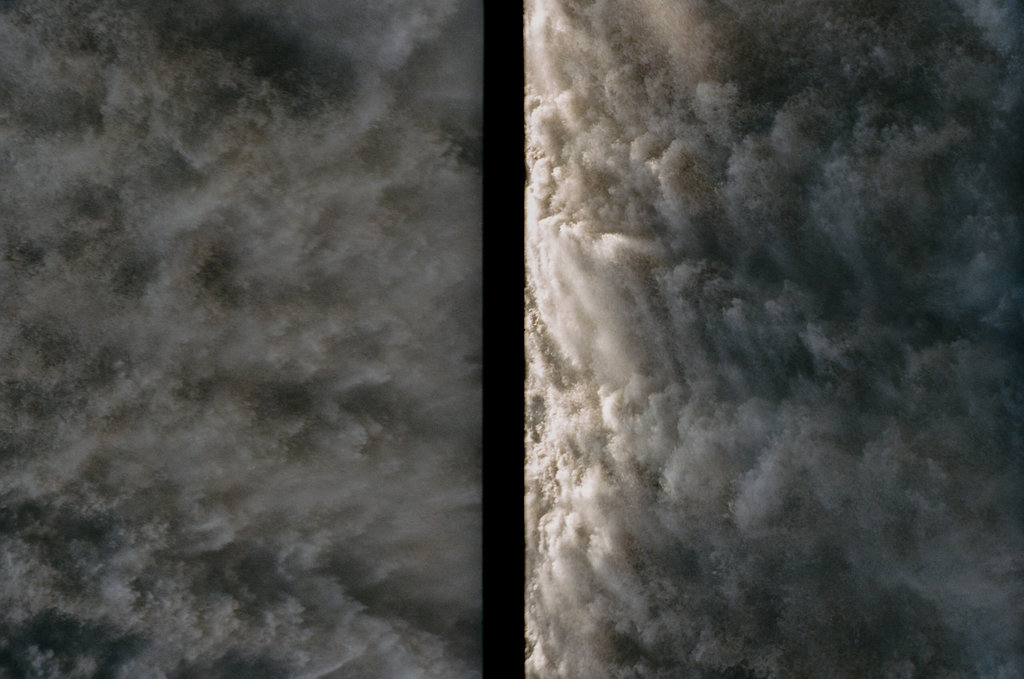

jen berean: One of the most recent works that I’ve seen of yours was Clouds in Central Park, which will be there through the summer. Do you enjoy working on public sculptures? Is that something you want to do more of?

olaf breuning: The thing is, I like to do it all. When someone like the Public Art Fund comes to me and gives me an opportunity to make a work with them, I will do it because I’ve liked what they have been doing for a long time. They work with many famous artists, so it was an honor for me to do be asked to do something with them. Also for example, I did a shoot for Purple magazine yesterday. I like that magazine very much. I’m not someone who categorizes so much, “Oh, is it fashion? Oh, is it pottery?” So long as I can bring my language into it, I don’t give a shit what it is.

jb: Your work does appear in many different fields. You’ve been a part of a few collaborations in the fashion industry. There was the collaboration with Bally and with Surface to Air. Do you consider all of that as part of your practice?

ob: Sure. I have to take a little bit back, because whenever I am involved in a collaboration, there are compromises. With my work I normally don’t compromise. For Purple, all I knew is that I had to have the model wearing Louis Vuitton. I felt quite free, and they practically let me do what I wanted. There are some collaborations where there are more restrictions. You always have restrictions in public art. The most uncompromised way to work is in your studio and have gallery and museum shows. Public art is an extension of your artwork with a lot of compromises involved. But it’s definitely a new dimension of scale. That’s why I like to do it next to my other art productions.

I’m not someone who categorizes so much, ‘Oh, is it fashion? Oh, is it pottery?’ So long as I can bring my language into it, I don’t give a shit what it is.

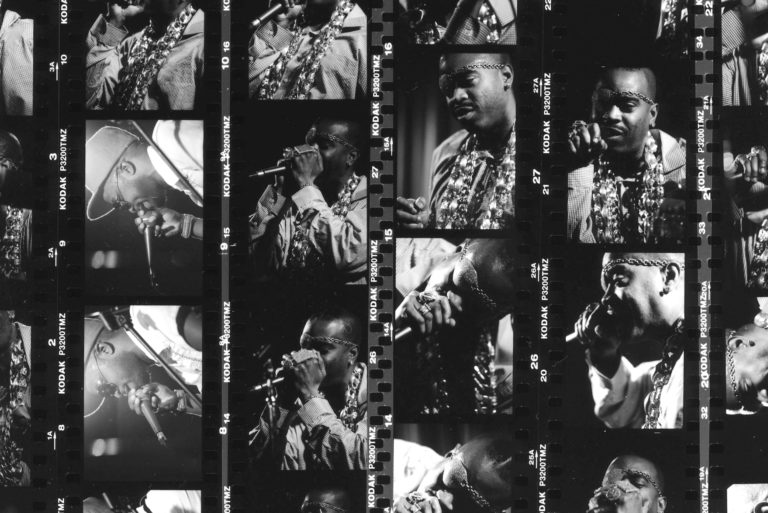

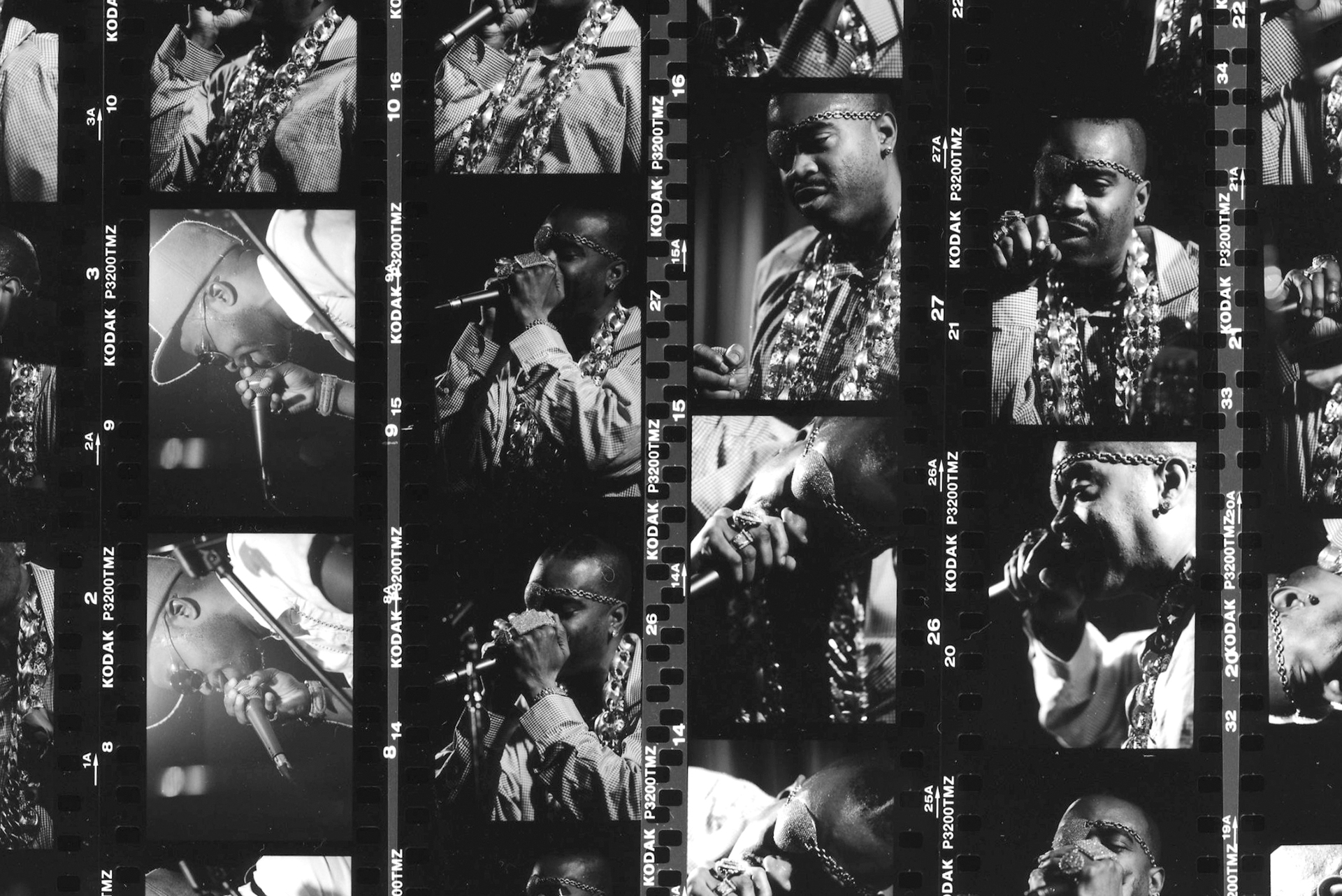

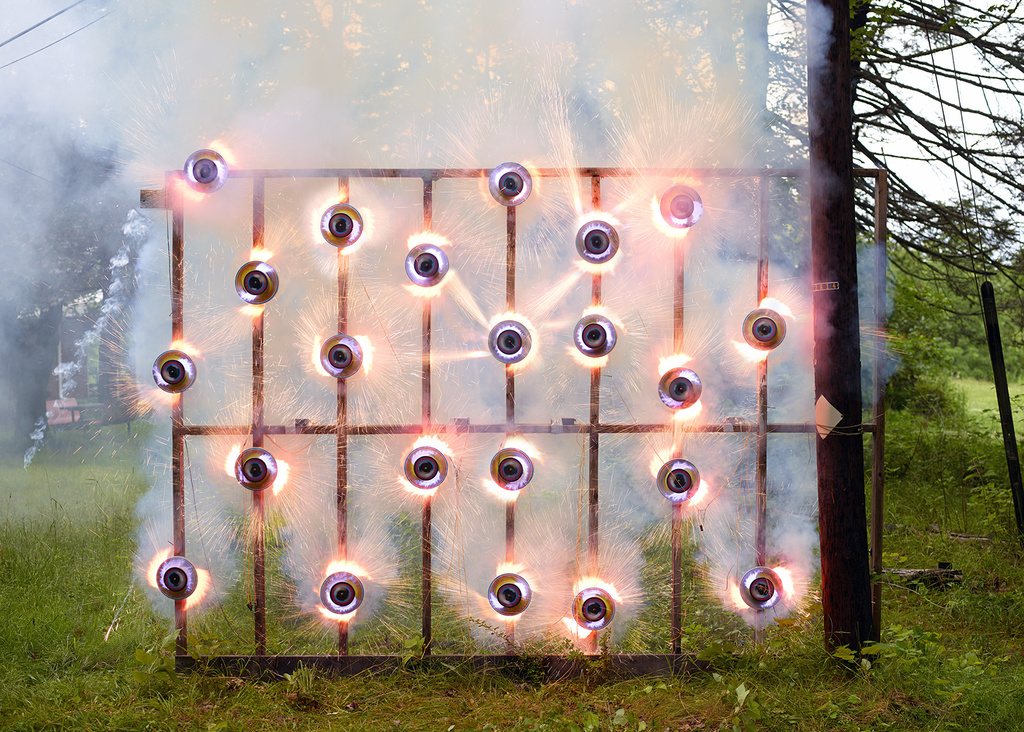

The Art Freaks, 2011 Photos: Olaf Breuning

jb: Are your public works simply bigger versions of what you make in the studio?

ob: Kind of. I still don’t know what I should think about it, honestly. I like to do it, because I come up with an idea and other people build it. Then I can walk around it and look at it and think, “Great. Huge. Impressive.” Maybe it’s different to my other works, because with tons of steel you cannot just crumble it like an unsuccessful drawing and throw it over your shoulder into a garbage can. It’s more a serious business.

jb: But with public art the audience is much bigger and there is an indirect encounter with the sculptures that you wouldn’t get in a gallery. A gallery has a very specific audience. If your work is in Central Park, or if it’s in a plaza in Toronto, the users of those spaces and a wider public is going to see it every day as they pass by.

ob: It is a funny thing. Even though I know millions of people see the Clouds at Central Park, I also don’t know what that means today with so much information around. We are in an over-saturated world where so many people are more creative than ever. With the sneakers you buy online, you can choose the colors and design them yourself. That’s why when I think about this big piece outside in Central Park—probably the most visible piece I have done—I wonder, besides the fact that it gets a lot of posts on Instagram, what is the impact of it? I don’t know. It seems to be just another creative output in a colorful city like New York. But I don’t care, I love that work and that alone makes me happy.

jb: Are you on Instagram?

ob: I am and I’ll check it. I search for hashtags of the Clouds work and see that it gets posted a lot. But the guy who posts cat photos also gets millions of hits. To have hits today doesn’t mean anything really. Like a small baby who sticks a spoon in its ear has two million hits for five seconds. But still, I like Instagram a lot better than Facebook.

Good News Bad News, 2008

Photo: Olaf Breuning

jb: Do you like being on the other side of the camera?

ob: I cannot say that I like it, but I don’t really care. It’s because I’m often on the photographer’s side that I want to make it easy for him. But I don’t know. The only things I know are related to my art. I like to produce art.

jb: You have made a lot of work about other artist’s work. Like The Art Freaks, where you mimicked the signature styles of seminal artists’ work through body painting. What led you to making those?

ob: I always believe that as an artist you can talk a lot about life and this world in a general way. But somehow, all of a sudden, it was an urgent desire of mine to talk about art. I think art is repeating itself. It is in a kind of limbo. I really believe that all of the big pioneer works are more or less done. Today in contemporary art—and in music, fashion, film and many other creative productions—we are working with a big archive, and it’s a recycling of this archive. You can actually take something out of the archive, which was produced 20 years ago, just change it and make it your own and that’s about it. For me, as an artist, I always have the fantasy to still produce pioneer works. But I know that these times are over. With The Art Freaks, for example, I referenced Warhol and his Marilyns. These iconic works are in all of our minds. When you think about art, you think about Andy Warhol, you think of his Marilyns. The archive is very strong today. We cannot avoid looking at it and talking about it.

jb: Especially with the Internet. It’s so accessible and it’s so easy for anyone to just get an image or rework an image. Your website is really active. It feels like you post on there all the time. Is that an important part of your studio?

ob: That’s an important part for me. I always want to do something new. After the Purple magazine shoot yesterday, I had to hold my hand to stop from publishing it on my page, because usually when I do something it goes on my page. The page for me is like my workbook.

jb: It’s like a sketchbook.

ob: Right, exactly.

I open the doors for people in my art and I let people in. And when they are in, they might be confused.

jb: Most of the artists you reference in The Art Freaks are no longer alive, but there are some that are living artists. Have they ever had any comments about that work?

ob: Maybe they would say something, but I haven’t met a living artist that I referenced after I shot this series.

jb: These works are really interesting, because you directly reference other artists’ work and reinterpret it in a very Olaf Breuning style. And by painting directly onto people’s bodies, you present an intimate and very personal take on some pivotal moments in recent art history. The work seems like a kind of human cataloguing of trends in contemporary art. What are your thoughts on current trends that you can see in the art world?

ob: There’s something about talking about it that sometimes makes me a little angry, because I believe that, especially today, a lot of artists have a very narrow worldview. They are focused inward on art. The good students coming from art school now know exactly how to move right into the art world. But no one cares to have a language outside of the art community. I just miss the authorship in art, the heart and the intensity. I went to the Whitney Biennial, for example, and I’ll see some pottery standing there, beautiful pottery. I don’t know what else I could see except that it’s nice pottery, and why would I have to go to a museum to see nice pottery and to think about what it tells me? And when it tells me something it’s so academically loaded. It’s fucking masturbation from the beginning to the end. I like artists who have character, who have a language, who say something about whatever. But I’ve complained enough. I’m a complainer.

Olaf at his Upstate NY home

Photo: David Schulze

jb: So who is an artist who you think is doing great work right now?

ob: There are always great works produced, and the possibility of this is even bigger because there are many more artists active today than let’s say 50 years ago. Like I said, I don’t care if an artist is working super dry and conceptual, but it is not my favorite way of working. I like an artist like Paul McCarthy more. As long as I feel as honest dedication behind it, I am fine. When I smell calculated bullshit, I am out! Stereotypical contemporary art pieces demanded by the art market and served by the artist, this is not my idea of what an artist should be.

david schulze: I’m going to hijack and ask a question, because I’m very intrigued. You said earlier that you felt that the art world was in a very small circle moving along at the same speed, and they’re all just oscillating around each other and lifting each other up, that it’s not very inclusive for people outside. Do you feel like your work, because it has such a big sense of humor, is a deliberate ploy to fuck with those people who are in the art community?

ob: I open the doors for people in my art and I let people in. And when they are in, they might be confused. The type of artists I was talking about before, they close the door, and this moment for me is something very arrogant because they close the door, and it’s written on the door: “Entrance Only for People Who Studied Art History and Know Shit About Art.” Otherwise you’re just out. This exclusivity—and maybe it is necessary for art to protect itself from the over-saturated creative world around it—makes everything so precious. Maybe artists will realize that we don’t really need art anymore today, because there are other ways of being culturally critical. Advertising can be critical, even fashion labels are sometimes critical. Contemporary art has maybe lost a bit of the role that it played in the last century.

Skeletons, 2002

Black Images, 2009

Color Wheels, 2012

Emojis, 2014

Fry Eye, 2013

Black Images, 2009

ds: You want your stories to reach as many people as possible. You’re actually putting your stories out there so that everyone can understand, not in a simple way, but it’s very clear what you’re saying, whereas the other type of conceptual work you speak about is very convoluted. Is that one way of looking at it?

ob: Let’s just stop speaking about academic art works. I sound like an angry grandfather by complaining about this and I actually don’t want to come across like that. I definitely should hire an assistant who kicks my leg under the table when I have an interview, reminding me that life is good and there is absolutely nothing to complain about.

jb: Well, let’s not look at it as complaining, but rather voicing an opinion. But while we are on the topic of complaining, one of the most complained about factions of the art world these days are the art fairs. Do you go to art fairs at all? I know you made a big sand sculpture on the beach in Miami in 2008.

ob: I got to the Miami art fairs sometimes, because it is always fun to see the art community a little drunk under a palm tree. But otherwise, I think art fairs are not really nice for artists. When I go to them, my eyes shut down after five minutes. There are just too many things at these fairs. Maybe it is because we as artists take our work very seriously and when you see your work hanging there like another sausage in a meat market. I cannot take that.

jb: I think this mixture of art and commerce can be difficult for artists to process. I saw an exhibition recently which made me think of this problematic relationship. It was the Urs Fischer show within a Chase Bank on the Lower East Side. The bank was no longer used, covered in graffiti, and damaged on the interior. He put a series of bronze sculptures throughout it. You went to school with him I believe, no?

ob: Yes, we went to school together for a bit. He has a factory of like 30 or 40 people working for him. His way of working is so different—it’s like, Jeff Koons owns a factory, Ai Wei Wei owns a factory. This kind of artist is just so different. They become like entrepreneurs. They could make like tables, or whatever. I do think Urs Fischer is a good artist.

Olaf Upstate NY. Photo: David Schulze

jb: Do you ever have assistants?

ob: I did have a studio manager and tons of interns. But now without this, I feel all of a sudden very free. I realized that’s why I want to be an artist. I want to sleep as long as I want in the morning. I don’t want to be responsible for people, like a boss.

jb: So if you had the opportunity to have a factory like Jeff Koons, where you had 100 people working for you, do you think you would want to do that?

ob: I’m a very social person. I could definitely do it. I’d probably have it in my nature, but so far, I’m very happy that I don’t have to. The nice thing about being an artist is that I can do things like come up here and work for a few days on my own.

jb: You can draw analogies to music in what you are saying. Some music is really isolating, and it is about an understanding of musical history, and it doesn’t necessarily sound good to an untrained ear. I guess it’s just not as blatant as it is in the art world, because people will look at a blank, empty canvas on a wall and want answers.

ob: You are right, but actually I blame myself and think that I am like a stupid potato when I stand in front of a Robert Ryman painting, for example. I look at it and think, “Olaf, what the fuck is wrong with you? Are you an idiot?” Well, I might be one. But also I am very interested in storytelling, and most of the artists I like are those who tell something about life. But I do really understand why Ryman’s art is important. When Ryman painted his white canvases, it was a radical comment at the time. I just don’t understand how artists can do the same thing today. It is no longer groundbreaking. But, having said that, it all seems to make sense, since obviously nothing makes sense today.■