thomas bettridge: What’s your process like when you’re taking these Polaroids? Do you just wander around with a camera?

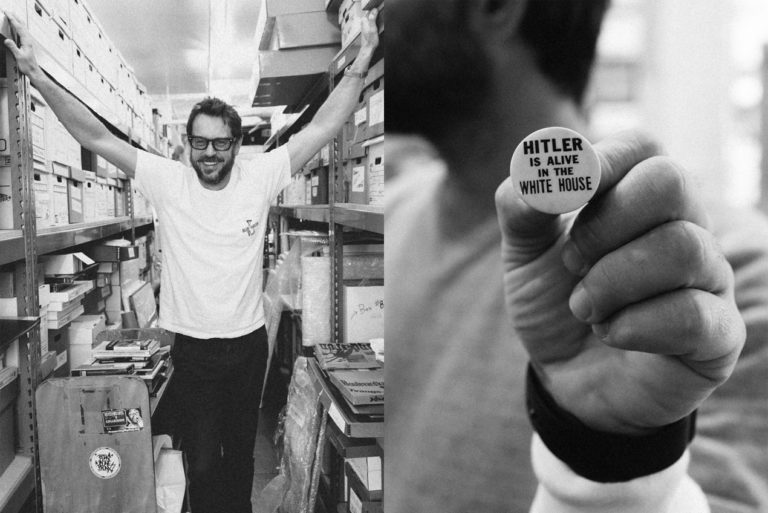

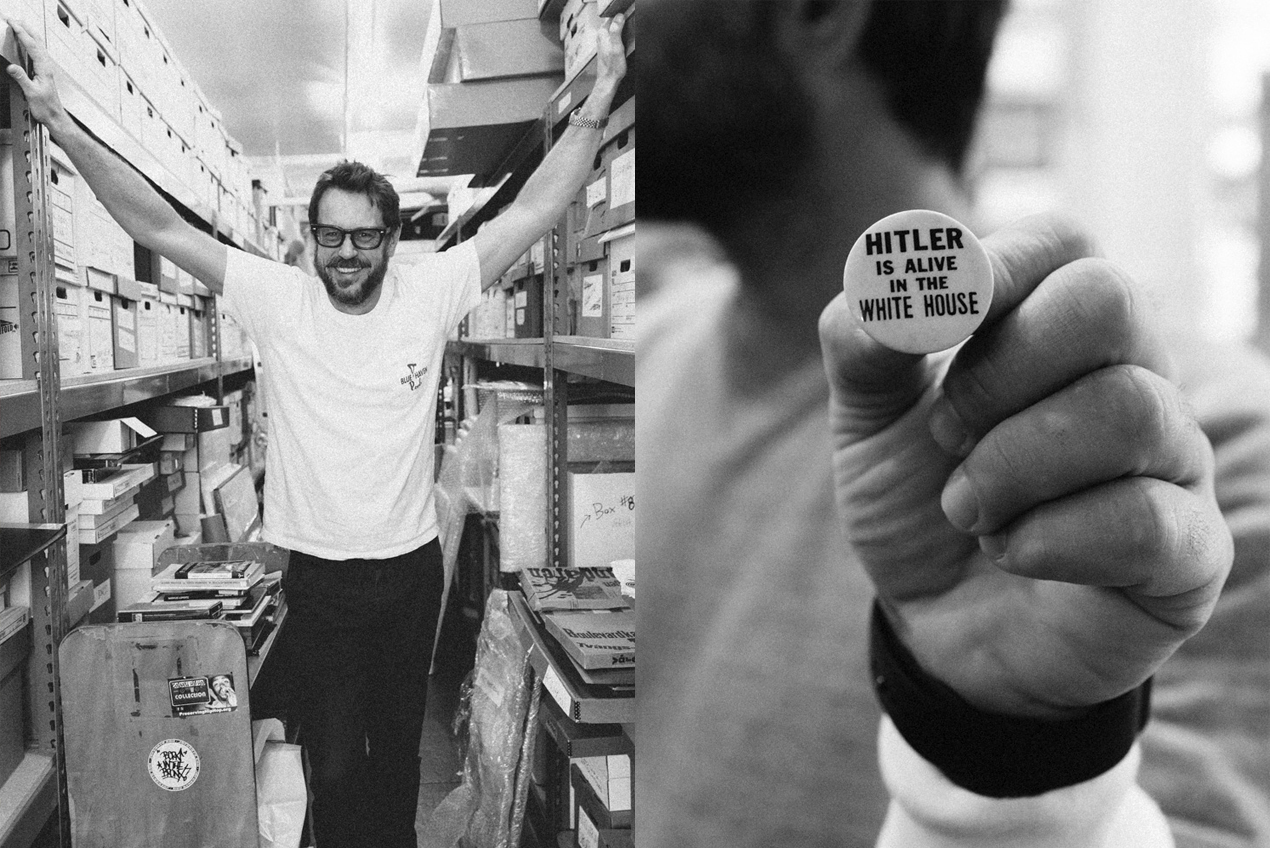

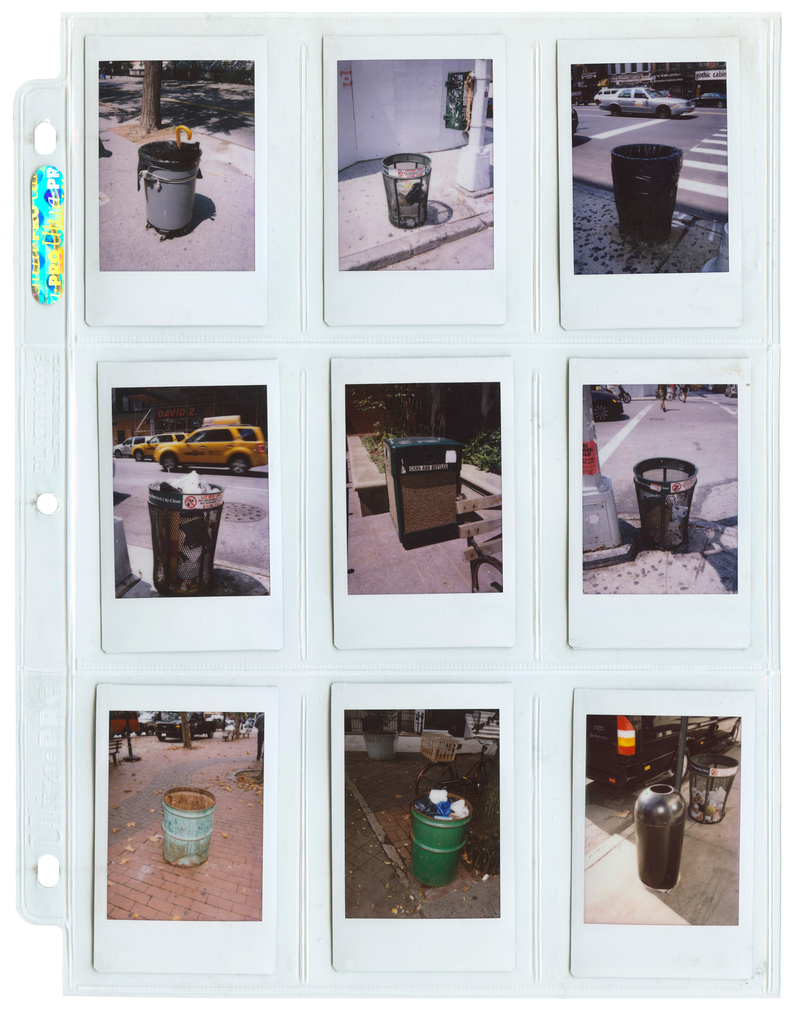

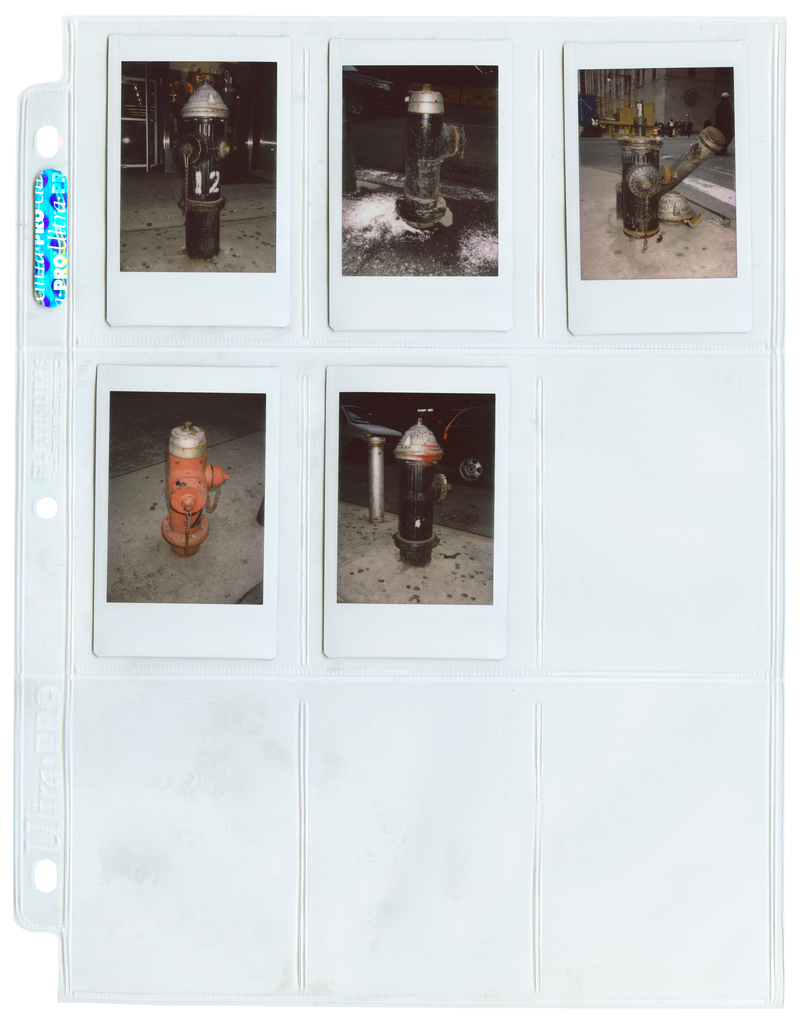

lucien smith: When I originally started them—when I was doing them in New York—I was always going on these bike rides in the early morning, or late at night, while I was walking home. At first I started out with park signs, and then it was garbage cans, and then some fire hydrants. I was literally trying to document as many of them as I could on my bike rides or strolls, and then it just became this habit where we were constantly trying to find new ones and different things. But it was less photography and more about collecting and archaeology.

tb: Did you set out at the beginning to make an archive of this size?

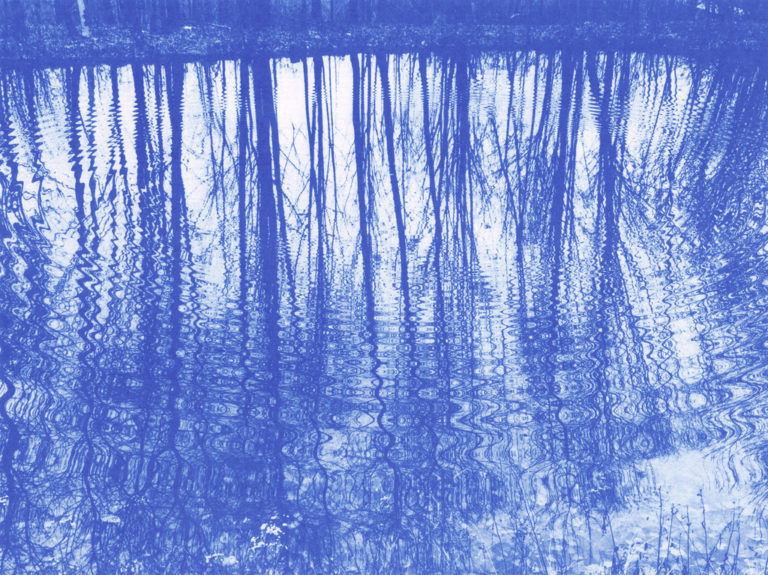

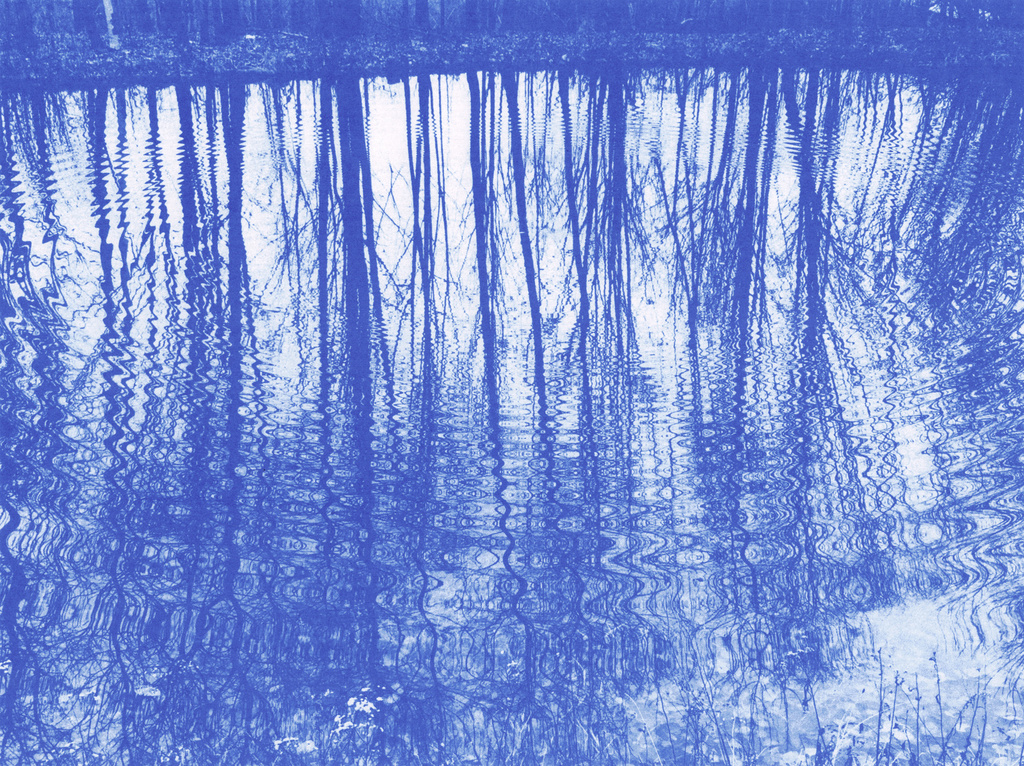

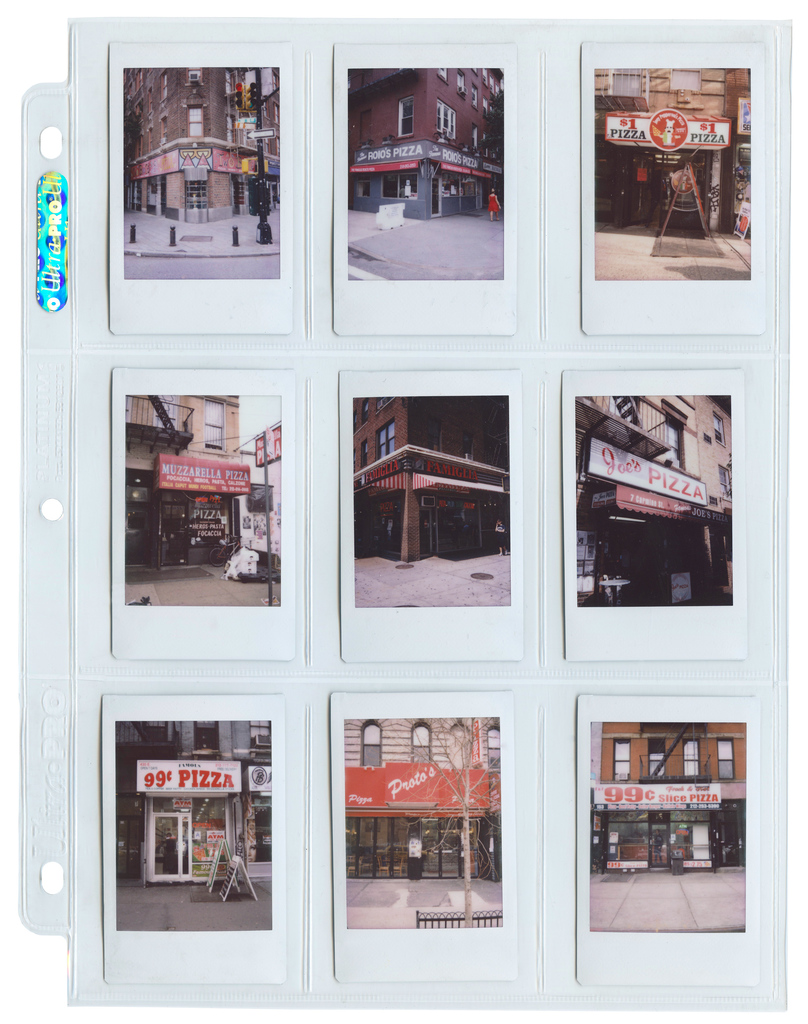

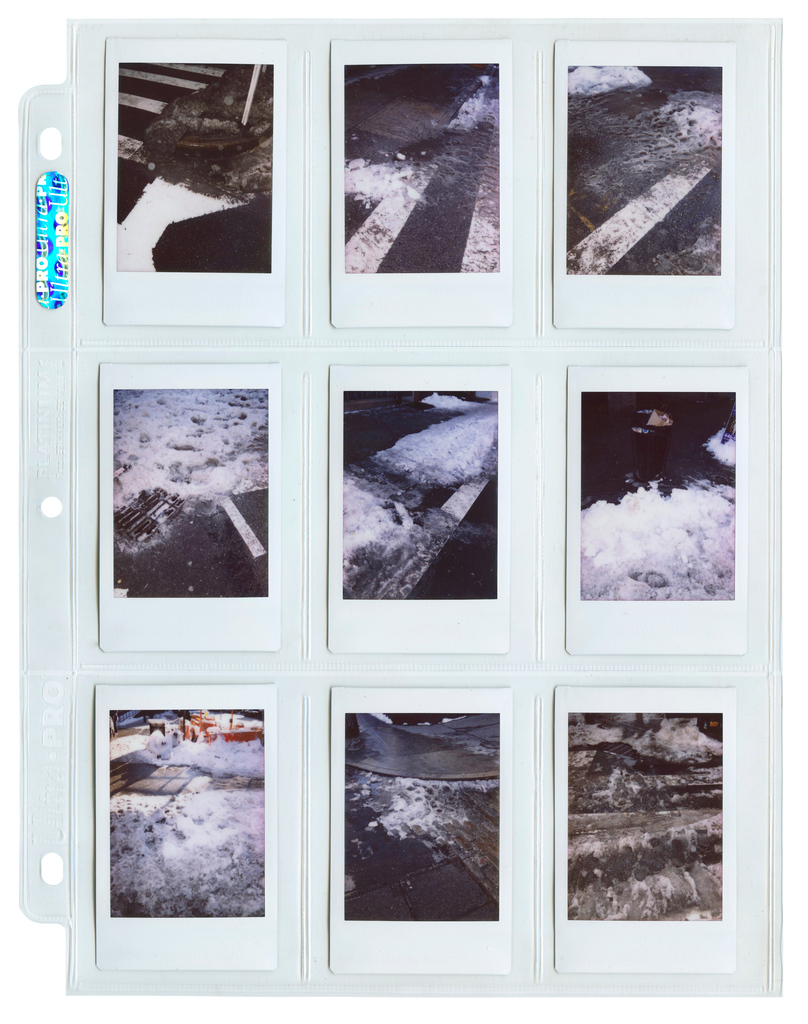

ls: It worked with the show that we were doing, which was really about the metamorphosis of New York, and all of its phases, and how you don’t really notice them until they’re gone. Simple things like the old trashcans versus the newer ones, and the park signs, and the things you take for granted. And then there were really ephemeral versions of that, where we were taking photos of puddles, photos of accumulated snow melting on crosswalks.

tb: And those Polaroids were originally shown alongside found objects, right?

ls: Exactly.

Beach, Montauk

Pizza, New York City

tb: With these new photos from Montauk, are you thinking about doing a sculptural installation with those as well, or is it more just the Polaroids?

ls: For the ones on the beach, there’s no real plan or exhibition for them. It’s mostly because lately, after this year, I’ve done a bunch of shows and I’ve really gotten turned off from working at that pace. So I’ve really just been working on my own schedule, not really painting as much, and taking a lot of photos. I probably won’t ever really show these new photographs, or at least I don’t have any plan to. That’s why I’m out here all summer. I’ve been going on hikes to the lighthouse and back, and I’ve just been taking this as a good opportunity to document that.

tb: Have you noticed new things doing this project out in Montauk as opposed to New York?

ls: It’s definitely a lot different, because when we were doing this in the city, I had arranged things that I really wanted to photograph. But on the beach here the options are so limited. At first it was just like, “Oh, I’ll photograph all of the trash.” But that began to seem a little obvious. So then I was basically just looking for anything that caught my eye, and that was more interesting, because then I started to find smaller things. Like, why are there always balloons on the beach? I thought about it and I realized that most end up going so high that they pop and land in the ocean, so eventually they get washed up. There’s a lot of those weird, little things that you don’t ever really notice. So that was lot more interesting.

Trash, New York City

luke flynn: It almost sounds like an escape from the regular painting that you’ve been doing. Is there a reason why you’re not doing as much painting? Are you trying to take a break?

ls: The past couple of years have moved really fast for me, and I don’t think I ever really got a chance to decide what kind of studio practice I wanted. Even calling it a “studio practice” actually makes me cringe, but I never really got to figure out the way I wanted to work. It was always just like, produce, produce, produce. I think I’ve reached a point now where I have some dead time, and I realized that I just wanted to start doing things at my own pace. So along with other stuff that I’ve been working on, that’s just been about doing things at a speed where it’s not interfering with my lifestyle. Escape is a good word, because this change of pace has been an escape.

tb: What other projects are you up to right now?

ls: We’re trying to put together a lot of photo books, some narratives, but in a simpler way, like how you would make a film. I’m almost finished editing this film called Snowy Say, and I really became interested in the way that works—the production of a film, with art directors and location scouting and all of these different elements that go into creating this larger overall thing. I look at these books in a similar way when we’re casting the people we want in the book, or finding locations. So one of the projects I’m working on now is about this natural spring in Florida called Weeki Wachee. They run this super weird mermaid show there where you watch underwater behind this glass as these mermaids swim around with these oxygen tubes attached to the ground, so eventually they all would go to get air. We’re going to try and shoot a story about this girl who works there.

Gutters, New York City

Beach, Montauk

tb: It does sound a lot like a film.

ls: Yeah, but it’s a book, just page by page.

tb: Do you see projects like this as an extension of your painting practice, or is it a separate thing in your mind?

ls: Definitely an extension. But I think part of it is about starting to find out that painting isn’t the most important medium to me. I don’t think there really is a most important one, but I’m definitely looking at photography as a way to get across ideas that don’t need to be painted. I used to constantly get in this situation where I would find an image, or find something that I wanted to show, and I felt like the only way it could get looked at, or viewed as art, is if I painted it. That was such a backwards way of thinking. To me, the idea of immediacy just makes more sense. Unless there is a reason why it needs to be painted, it can exist in a photograph.

Snow, New York City

I used to constantly get in this situation where I would find an image, or find something that I wanted to show, and I felt like the only way it could get looked at, or viewed as art, is if I painted it. That was such a backwards way of thinking. To me, the idea of immediacy just makes more sense. Unless there is a reason why it needs to be painted, it can exist in a photograph.

tb: Medium specificity can be such a tired idea.

ls: Like I said, I was young and I maybe looked at certain things in the wrong way. I thought, “Oh, the market wants paintings, so everything has to be painted for it to be looked at as valuable and important.” Now, entertaining any sort of market or audience doesn’t really interest me at all. I’m free to create whatever I want.

lf: Do you feel like there’s a lot of pressure, because you got a lot of attention when you were quite young?

ls: There definitely was pressure. I’m not sure if it was in a negative way, but it influenced decisions that I was making at some points. It’s interesting when people are spending half a million dollars on paintings that you made when you were nineteen, or 20. I didn’t really know what to think about that.

Beach, Montauk

Beach, Montauk

lf: Honestly, it sounds really good.

ls: It was also cool. You make something with your hands, and it turns into money. That’s fun, but I made art because it was something that made me feel good from the early stages of being a kid. Turning that into a job or something financial like that is kind of perverted, the idea of it. So I’ve been trying to find that place of making it from a genuine starting point, where the original idea that we’re making it from is something that interests me rather than the thing that is going to make me more financially stable. I just needed time. I needed to learn lessons in whatever ways I needed to, the harder ways. I’m 25 and I’m in a pretty good position. I have that freedom now to be able to create and finance things that maybe I wouldn’t have been able to do normally.

tb: Your show Tigris at Skarstedt Gallery just closed. What was it like for you showing in that uptown context?

ls: It was a really good experience. Even at that point, planning the show, I was a little hesitant to want to do any sort of installation of paintings. I was so over it. But one of the things that really convinced me to do that show was that it was in a space that wasn’t a white cube. It wasn’t your ordinary Chelsea gallery. The space had a lot of character to it. Part of that thing I’m bummed about recently is that every month there’s a handful of shows in the most popular galleries that people travel to, and every month they take down one artist’s work and put up another artist’s work, and the space doesn’t really change. It’s like a showroom, or a store, and I wasn’t into that anymore. I didn’t want to be another artist—another notch on the belt of a gallery. So doing a show following Martin Kippenberger and being in that context was really exciting.

Fire, New York City

lf: Was there anyone that hated on the idea that this young kid was doing a show in that kind of space?

ls: I think it was a lot harder to find someone who wasn’t hating on it. But that stuff never really matters. I’ve dealt with criticism over and over again, and sometimes I even agree with it, which is the crazy thing. But the only thing I can do is continue to do what I’m doing. I can’t let that sort of stuff motivate me.■