khari clarke:As a kid and during your teenage years, I remember you were into modeling. What made you go from in front of the camera as a model, to behind the camera as a photographer?

lorenzo holder: While I was modeling, I thought I had an idea of what it took to be successful in that industry, but along the way I learned what it really took. Basically, I realized that I was not model material. So I moved forward to discover what my true passion was.

kc: What were some of the reasons you were being denied?

lh: Because you know, in modeling being “in shape” is key, and I wasn’t “in shape”. I was just a sleek, slender dude. And the market…the way the industry was going, I just wasn’t what was “in”.

kc: So one door closed and the next door opened…?

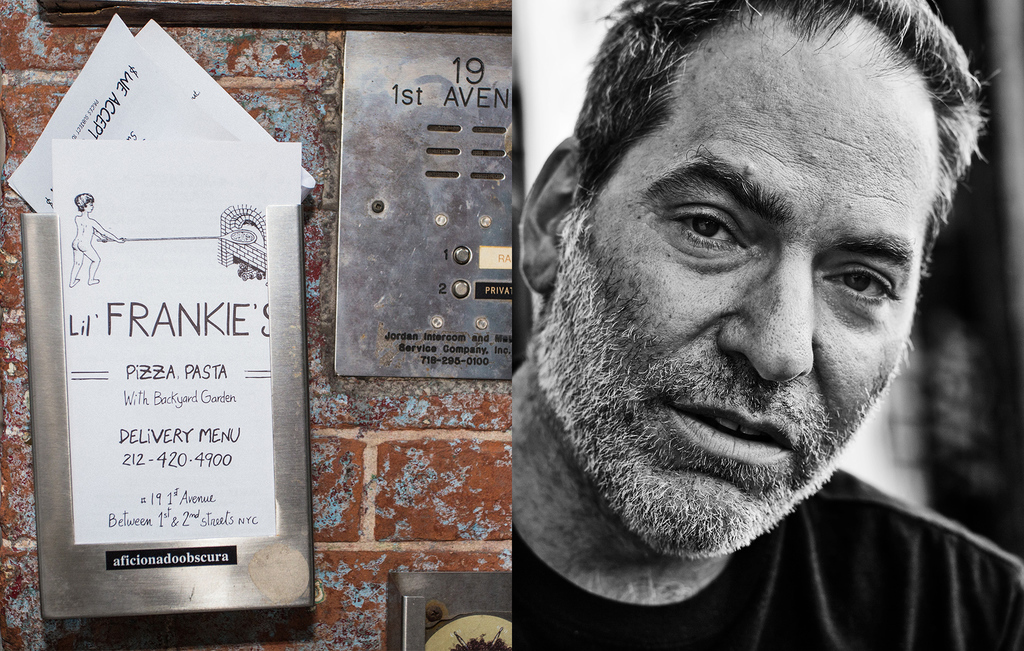

lh: It’s such a long story … basically I wanted to invest in building my portfolio, so I did a photoshoot and met my good friend Cavier. He was a photographer—a young, black photographer—and I was like “wow, this dude is living in New York, paying his bills from photography.” It didnt seem easy to do, but he’s still doing it. I was inspired to see a young man discard the standards of working a 9 to 5, and utilize his talents to finance his life. So I began shooting, everything. Continued developing my own style and building relationships with clients and decided to quit the retail life to devote my life to photography.

kc: So when you first started, before you really started traveling, what kind of photography were you doing?

lh: In the very beginning, I was really just shooting my friends, and luckily a lot of them were models and signed to agencies. So I would shoot them, and email the images to their agencies. I began building relationships with them and they would send me more models to shoot. In that journey, I got to see how much taking the time to create great imagery with people can serve a purpose and help someone on their journey. A lot of the models are really young, 16, 17 years old, from the middle of nowhere, who have been quickly submerged in the New York dynamics. With me being a model at one point, I felt it was important to impart knowledge from my experience to help guide them to success.

kc: I’m sure this wasn’t a fly-by-night kind of deal, what was the period between quitting your job and actually having a steady flow?

lh: Man, it was extremely difficult. It kind of—it really changed my life—in a good way and bad way. There was a point when nobody believed [in me]. Money was low, I was living with my mom off of about $150 every month. I sacrificed everything because I knew I was doing what I loved. Some days I wouldn’t eat, but I kept going because I knew that I was doing what felt right. I don’t even know what I was riding off of—it was really a belief that maybe I would get to a point where I would be making a living shooting. I had to stay persistent and focused.

kc: Did you go to college?

lh: Some college. But, not for photography.

kc: So how’d you know you were actually good at photography? People tend to think they’re good, and our generation glorifies this “D.I.Y.” culture, but how did you know your work was actually quality?

lh: At the end of the day, it came down to that tangible image. There were moments where I would look at some of my shots like, “wow this is fucking great!” And then I saw that the response was great, and I knew it served the purpose. I might’ve even got paid for it. So, these reaffirmations let me know I was producing the right image.

kc: You kinda touched on my next question which is, how do you know when you’ve found the “perfect picture”?

lh: The eye is so unique and important, man. And for me, I’m low-key a judgmental person, OCD type actually, when it comes to shape, colors, you know—aesthetics. You’re not going to produce a quality image that captures the heart of the consumer without incorporating your own authenticity. I’ve realized this more now that I’m working in the corporate sector of art. I’ve work alongside people with all types of degrees— and if they don’t have swag, style, or unique perspectives, the image won’t translate! A perfect picture to me is an image that serves is purpose—whether to shock, share information, sell a product, stir controversy. The image must have context!

kc: Let’s get into your travels — when did you start to pick up and travel? How did that start and why?

lh: I was actually at a really low point emotionally, just grinding, shooting—It was a time in my life where I was struggling to find my creative voice. I met Ayo, my now girlfriend, at Afro punk Festival—incredibly dope woman. A doctor, Harvard and Columbia graduate, athlete, etcetera, etcetera. We started talking for a while and built a friendship. One day, she showed me camera phone images of her time in India the year prior—images of people with leprosy. My mind was blown by how she described her experiences. I wasn’t aware leprosy still existed. I immediately realized there was so much I hadn’t experienced. At that point, I’d still never been on an airplane in my life. I always wanted to have a reason to travel. I wanted to do work or come back with work if I left the country. I was so inspired, I told her “we’re going back”. And the rest was a blur man, business was good here in New York for a month or so and I was able to save up for a ticket. We made arrangements and next thing you know we landed in Hyderabad, India. That experience changed my life.

kc: So what exactly is Leprosy?

lh: Leprosy is acquired by a bacteria that can affect your skin, mucus membranes, and nerves, and can cause deformities. It’s such a deep disease. And, it’s looked upon like [puts hand up] “stay away”. Huge stigma. The big thing is, they get amputated — legs, toes, hands, fingers — constantly. So we figured we wanted to do something to wake people up let them know that leprosy is not just something in the Bible. It is in India, it is in other countries. There’s no reason why individuals in leprosy colonies should be ostracized from hospital treatment. At least, we want to normalize them, humanize them in a way to provoke others to be more empathetic. So I set out to capture their true essence.

kc: How did people feel being photographed? Were they uncomfortable?

lh: I feel like in India I saw the most unmanicured expressions. For example, in America if you ask someone to take a picture, they’re fixing their tie, they’re fixing their hair, they’ll stand up straight, it is not truly candid. In India, they didn’t understand how dynamic I was going to take the image, I wanted to get into their soul, in their eyes. The big thing for me was that I wanted to capture them smiling, even if it was with their eyes. True visceral expressions. So I would scream, “ Smile,” and we had a translator who would scream “Smile!” in their native tongue, Telugu. It was definite a shock factor, but they accepted it, they accepted me, and once we got on a roll, they were taking family pictures, they were asking for me to take more photos of them. It was great.

kc: What was the difference between the colonies you visited in India and Kenya?

lh: So, in Kenya it was a little different. I went to a leprosy colony there, but a huge part of our trip was linking up with a group of nurses who were doing a pop-up clinic in a slum neighborhood, called “Korogocho” in Nairobi. We did a pop-up clinic in their community center and also did home visits. [Pulls up a picture] This right here is St. Joseph’s School, it’s an elementary school in Korogocho. Right behind it is a dump like 14-miles long: burning garbage, crime, and serious gang wars in there… right behind the school! Pollution and smoke entering the windows of the school as the kids are practicing their music instruments. It’s crazy to fathom. There is not much support. Kids go there everyday for school! They’re uniforms—ripped up! I couldn’t believe it. I mean [as kids] if we had like one hole in our uniform, you’d ask your mom to get you a new one. The kids did not know of such, “luxury”. The things we take for granted, man.

kc: How inviting were they to you?

lh: So it’s interesting… In Kenya, I was also with white people and they were a little hostile with them. Not like aggressive, but —

kc: Apprehensive?

lh: Yeah, they’d say “white people what are you here to do? You bringing us clean water?” They were hesitant of the intentions, but were still grateful. They were accepting of me. I called them “brother”, we called each other “brother”, and I looked them in their eyes. Shook hands. Played with the kids. Really made it a point to understand who they were and what they were going through. I asked them how their day was going, I asked them, “What’s your situation? This is your house? This your store? Yo, let me buy something.” We had three guys who were former gang members taking us around, showing us the ins and outs of the slums and the rest of the city. They knew who was really ill in town, so they were taking us around to certain homes and making sure we were taking care of the right people. They were accepting of me being there, taking pictures. They welcomed us into their homes, their current situations. But you know, I still had to be aware.

kc: What about India? Any apprehension? Any—

lh: You know what’s crazy, in India, it was love everywhere! We plan to go back to India, pretty soon, and with this trip I really want to take it to the next level. Of course, with permission from the people at the colonies, I want to take updated images of them, because I feel like the images I took of them—the portraits—

kc: Amazing portraits by the way.

lh: Thank you. I really want people in India – I want the whole world to know — to understand this shit is real and it’s still here, and that they’re right next to you. If you ask a middle or upperclass person about leprosy in their country they will look at you with oblivion, ignorance to be honest. These people are there. Living. Struggling. Begging. Surviving, and still finding a reason to smile. You probably see them when they panhandle, I want you to know that it’s leprosy and they’re beautiful. This person deserves hospital attention at the very least. I want to take updated portraits of them. And find where they’re at now, emotionally, physically, mentally, spiritually, visually, and capture it. And make poster prints, pretty huge, and post them around the city, Hyderabad specifically. I want to post them on the walls in the city!

kc: Guerilla-style?

lh: Guerilla-style, in the middle of the night. So they can wake up to change.

kc: What changes strategically between when you’re shooting models for portfolios, getting in-the-moment shots during your travels, and your more recent product photography?

lh: Strategically, when I’m shooting models for portfolios, I have to step outside of myself and really assess the situation. It’s really an informal kind of interaction. Initially, I don’t know anything about the model and I don’t really know what they look like in-person. I just have a few portfolio images and digitals their agent sent me. So, I have to scan the model and see what kind of energy they have to offer. Having an understanding of the industry helps, you know some things are kinda set-in-stone. There’s a way to do things, there’s a way to present yourself as a model, there’s a way you move and interact with the camera—so pulling that out of them is my focus. I guide them so we can create stylish imagery that will stand the test of time in their portfolio.

Now traveling is kinda similar in the sense that you have to survey the scene. You really have to feel the climate of wherever you are. Like if you’re walking into a slum, you have to look at peoples faces, shake hands, give hugs and say “hi”, smile, or at times give a mean mug, stand your ground and make sure no one is fucking around with you. Either way you need to feel. You need to feel so you can pick up on little nuance and create an image out of it. There is so much energy in the little things. Like, I’m intrigued by something as simple as someone putting a cigarette to their lips. Just that action is 100% iconic and we don’t even notice it half of the time, but we see the mystique of smoking in all type of movies and art. It’s immediately recognizable. My purpose in creating imagery is to highlight the little things. Elevating the things we are familiar with but pass by everyday. Things that we can relate to here in America that also happen in Africa and all over the world. Making that parallel is really important to me, especially being someone who has never been anywhere before my first trip to India in 2016.

Then product photography. same thing man, you got to FEEL! Like, when you’re handed a product you have to feel the product — Is it quality? Is it plasticky? As a consumer myself, I’m looking at the product and thinking “how does this need to be shown for someone to invest their feelings into it enough, to spend their money on this?” Where I work now, I shoot a lot of tech items. Headphones, and cellphone cases that are a little more fashion-forward. So understanding your demographic is really important. So overall, just feel and have an understanding of the situation.

kc: What is your ultimate goal with photography? What do you want your legacy to be?

lh: My ultimate goal with photography is to continue to produce work that illustrates life. I want to continue to put myself in situations that people aren’t familiar with. I want to show those things and normalize them. I want to teach people through my imagery. Not like some major life lessons, but like the small things. I want people to just realize, whatever it is they need to realize. My work isn’t “my work”, it’s life’s work. It’s life! I want to continue to be an open shutter—capturing everything that life has to give me. I want my backstory to be the inspiration behind it. Born and raised in Brooklyn, never really been anywhere— this is what this person saw, given not been exposed to much. Hopefully, I can inspire others to see, feel, and live their truth. I want my work to be the catalyst for learning and realization.■