miguel yatco: First question, where did you grow up?

fernando villela: I was born in São Paulo, Brazil, and lived there until I was 11, at which point our family moved to Europe, where I shared my adolescence between Belgium, Switzerland, and Austria.

my: What brought you to New York?

fv: Photography and New York. I’d fallen for the city when I visited on a family trip at the age of 15, and as I finished high school in Vienna, I knew I wanted to study photography so I applied to a few different schools, deciding on SVA for their reputation and location.

my: Do you think having been subjected to all of these different places has had any impact on the way you shoot?

fv: Definitely. Having to move countries so often and at such an early age, forced me to be able to befriend and connect with people wherever I was, while teaching me a great deal about different cultures and customs. I was very fortunate to have had a terrific education that exposed me to perspectives from all over the world, encouraged curiosity, and allowed me to discover myself despite geographic, cultural, or linguistic barriers. And walking the same streets as a lot of my early photography idols (Henri Cartier-Bresson, Josef Koudelka, Robert Capa, etc) also helped shape the way I saw my surroundings.

my: Do you have any other sources of inspiration for your images?

fv: Many. Living, dead, and inanimate. But if you want names, I could point to the street, and to the stunning works of Roy DeCarava, Ray Metzker, Diane Arbus, Paul Strand, Vivian Maier, Lee Friedlander, Harry Callahan; as well as the likes of Thomas Demand and Jeff Wall; Edward Hopper and Alex Katz; Fyodor Dostoevsky, Walter Benjamin, Friedrich Engels, Jean Beaudrillard, and many more.

my: Taking a step back and looking at your body of work, it’s evident that you’re capable of capturing a wide variety of themes and emotions, but what’s really interesting to me is how you portray New York. What are your thoughts on the way that you’ve photographed the city?

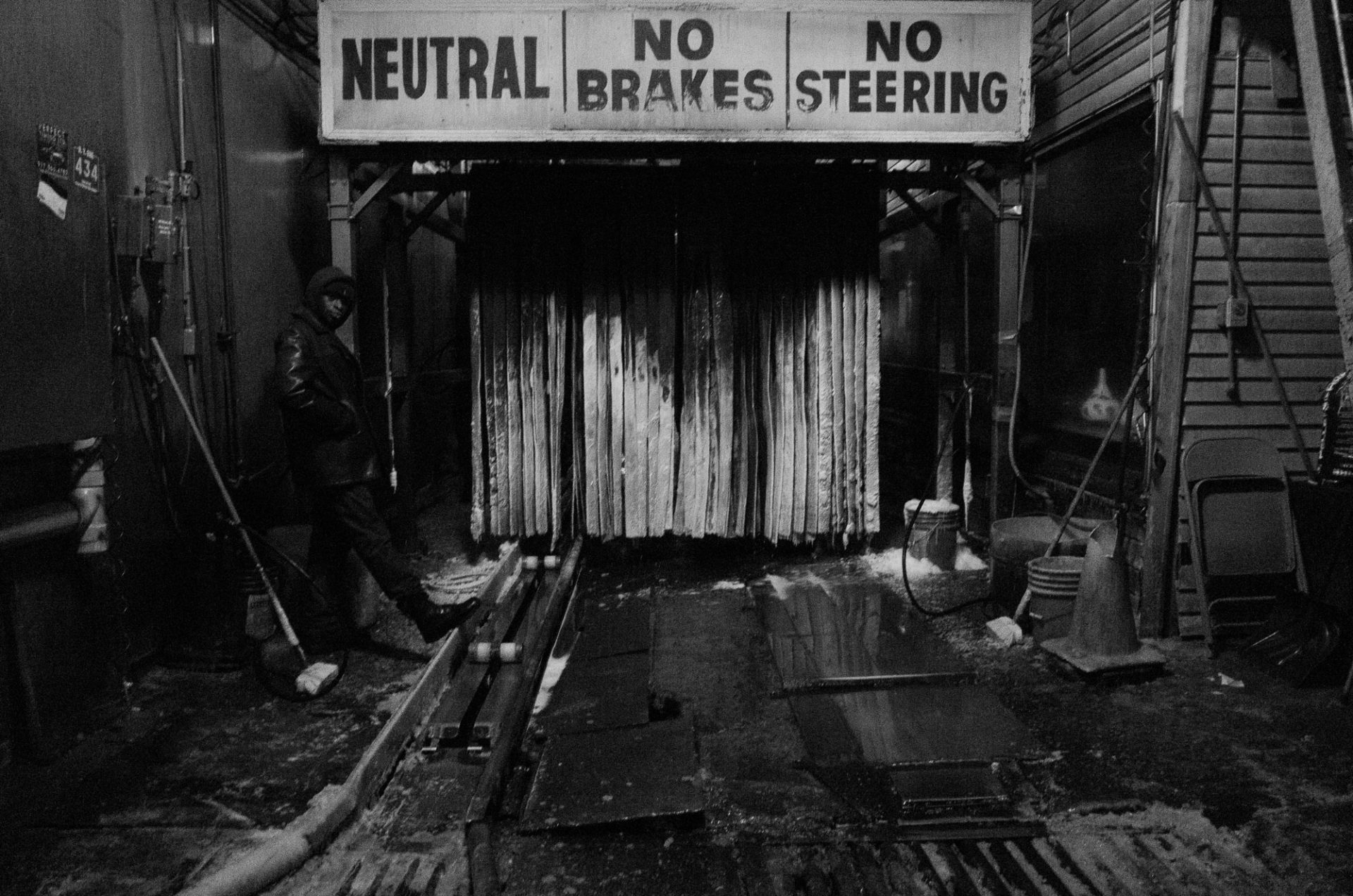

fv: That seems like a loaded question, but I try to portray it as I see and experience it. New York is everything and nothing like my hopes and expectations. It is fantastically grand and impressive, always alive and thumping, filled with incredible experiences and people from every section of the planet – it is home. But sometimes it looks nothing like a home, and for the almost 60 thousand homeless, that certainly is not the case. So I aim to photograph New York as it appears to me—an amalgam of promised prosperity and veiled desolation.

my: Is this how you imagined New York would look like through your perspective?

fv: Not quite. When I first arrived, I was intent on photographing the city as I had hoped it would be, rather than how it really was. As a wide-eyed 18-year-old in photo school, I was too excited about being in New York and playing in the darkroom, that it wasn’t until over a year into it that the deceptive façade began to peel away.

my: I also want to touch on the fact that you’ve used a Playstation game as a medium for your work and have garnered quite the attention online. Grand Theft Auto has always been a game known for its violence, hence quite popular with the kids, and for you to use it as form of art, can you tell us a bit about how the idea came about and what about the game that made you feel like it had this potential to be used as a medium?

fv: Speaking of deceptive façades…The idea for the work (Procedural Generation) came soon after I bought the game, when I found that you could take pictures from your avatar’s perspective. This got me really excited because of the ability to see and photograph from that first-person viewpoint. The virtual world ceased being just a background for insane driving and shootouts. These were not in-game screenshots anymore—they were photographs taken from a virtual character’s eye. So I set off to explore it, taking advantage of the benefits of a virtual reality: impunity (virtual pedestrians have no recourse should they object to my pictures), immortality (I can stand in the middle of the street to get the shot, and if I get run over, there isn’t a prohibitively expensive medical bill). I was also being exposed to a lot of existentialist theory at the time, and I found the parallels between that and the virtual people in my images rather exciting.

my: It’s really amazing how you were able to recreate your work in real life with a video game. What are your thoughts on that?

fv: I think it points to the convergence of the real and the virtual. After photographing in a simulated city, I began to see the reality around me very differently, and moving to Midtown Manhattan really accentuated those similarities. The rendered buildings, corporate lobbies, and alienated people of the original were, perhaps unsurprisingly, not so dissimilar to those of the simulation. This was a turning point in my work, leading me to use the camera to explore the illusory in the real and the invisible forces that carefully orchestrate it all.

my: What are you working on right now?

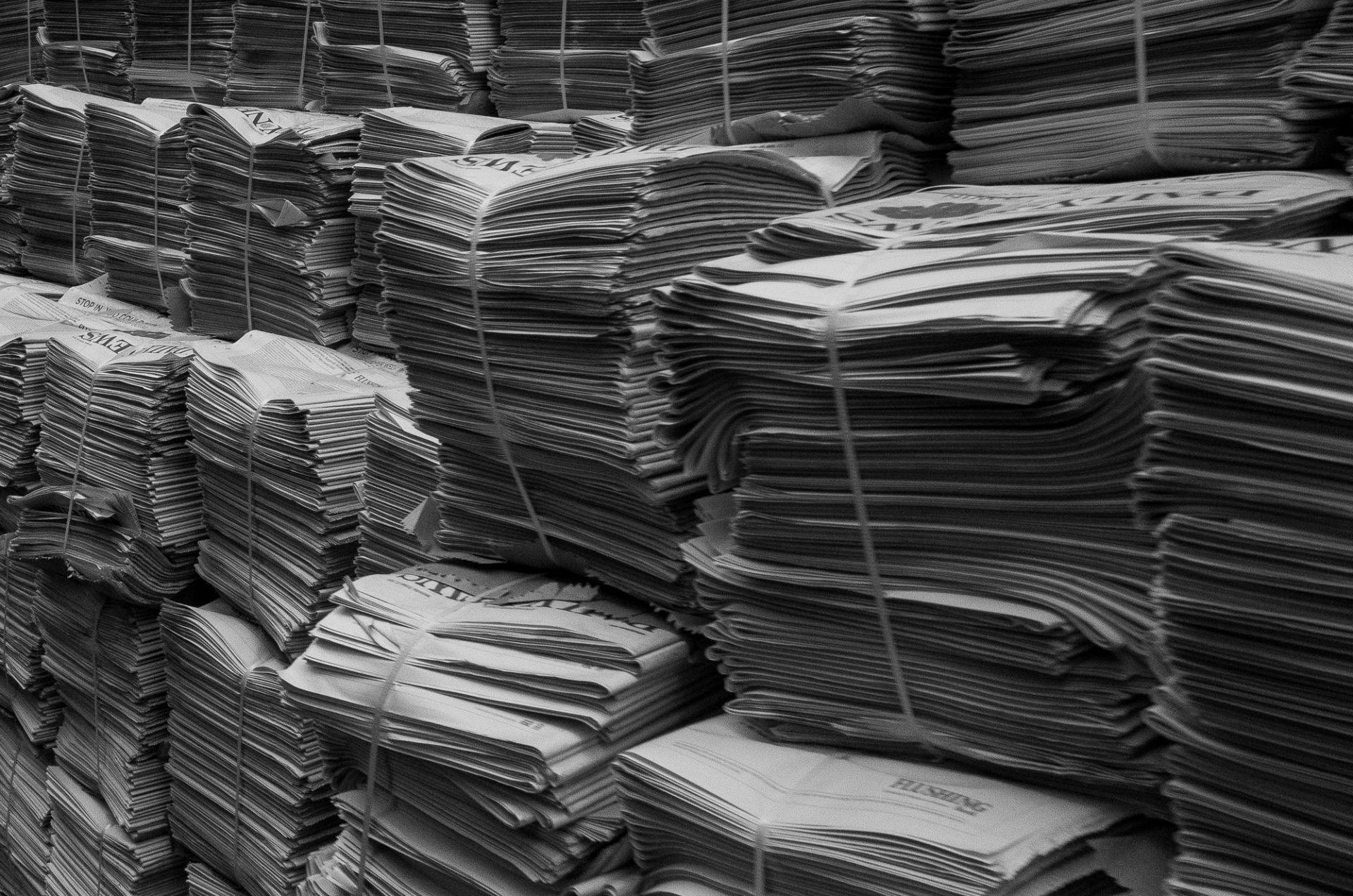

fv: I’m in an intense editing phase right now, seemingly never-ending, actually. I got a little lost in the first semester—not sure if due to the geopolitical climate or adjusting to a personal change in quitting traditional employment (I left my job the day he was elected). Without realizing I had begun to shoot a lot more than I ever had, but almost to an obsessive degree, looking for pictures in everything I saw. I now find myself weeding through several different sets of images, some are more along the lines of studies, while others of more classic photography; a few odd experiments, an unfinished video, and the continuation of my main focus—the consequences of an omnipotent, oppressive, and obscure system on a population, their relationships, and their environment. The latter has just been completed: Rest in Repressive Peace, along with its foil, Not the Road We Used to Know, which was shot this spring and summer, and examines the emerging signs of a promising new reality.

my: What’s in store for the future?

fv: Hopefully global revolution. But until then, I’d like to make some books, put together a few exhibitions, and dig away at the aforementioned myriad of in-progress projects.■

Find more of his work at www.fernandovillela.com.