I first met Vava Ribeiro in 1996. We were in Amsterdam, covering the 9th Annual High Times Cannabis Cup. We both worked as journalists—he in São Paulo, me in Los Angeles. A mutual friend had given us vague physical descriptions and told us to look out for each other. In an airy banquet room, a bearded and tie-dyed commune founder gave a lecture about growing pot, dodging the man, and ballin’ old ladies. He paused often and at great length. The audience crowded around him, sitting Indian style on the floor, severely stoned. When the lecturer paused, shook his dreadlocked head, giggled, and said, “Sorry, I forgot what I was sayin’,” the audience hardly noticed. I can’t remember whether it was during this lecture or the one about hydroponics that an audience member raised his hand and pointed to the passed-out guy next to him. They exchanged a few words. The lecturer became flustered. “Is there a doctor in the house?” he asked. “Hey man, anyone know CPR?”

In any case, it was after one of these, a pack of stoned audience members stepping out into a bright corridor, that I saw a guy who fit the description. Brown skinned, dark curly hair, big warm smile, two cameras dangling around his neck, a girl, tall and beautiful, at his side.

“Vava?”

“Jamie?”

We’ve been great friends ever since.

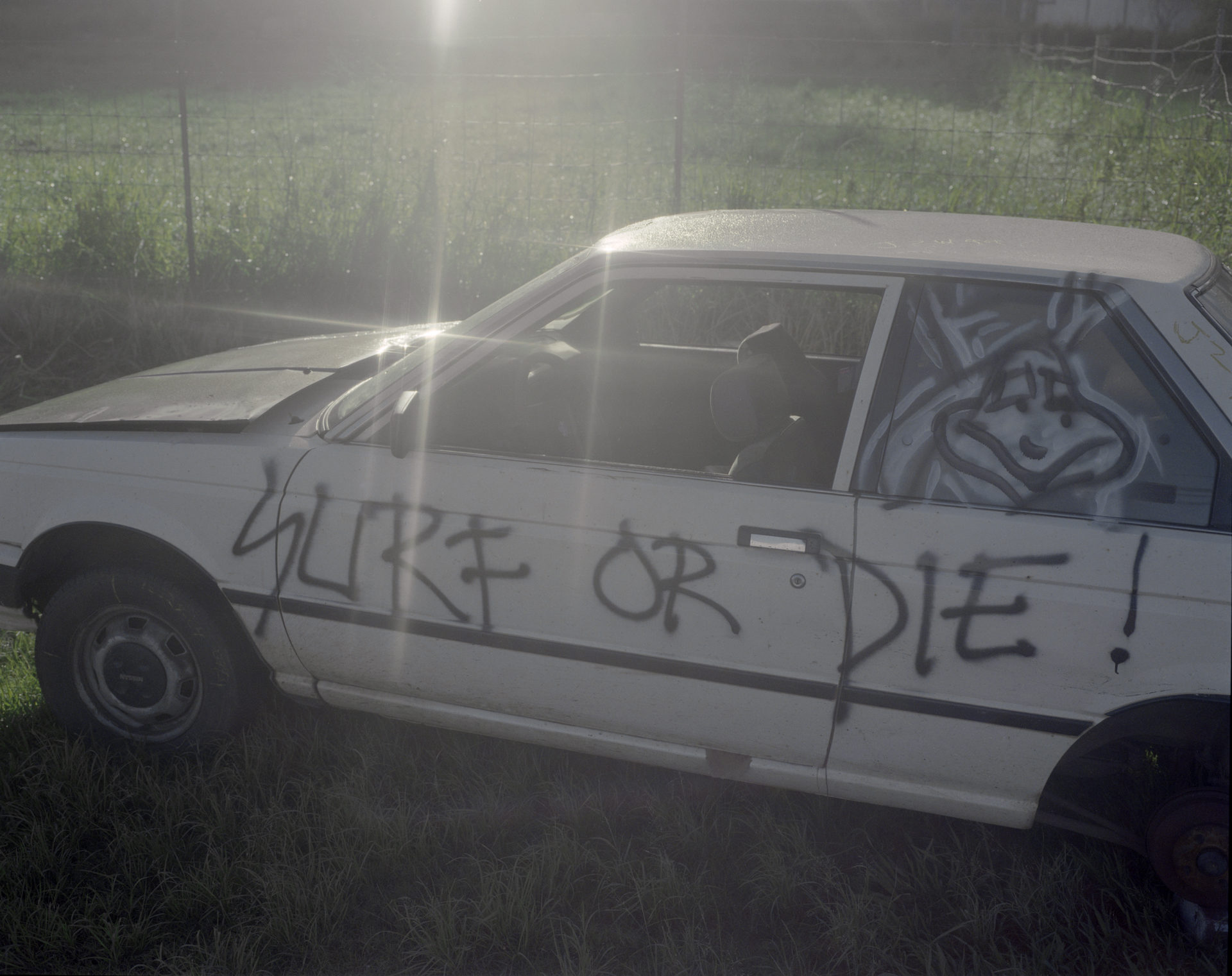

An adaptation of a mantra stolen from

skateboarding mags in the early ’80s. “Skate or die.”

Something that Christian Fletcher would dig.

Vava’s story goes something like this: The younger brother to two beautiful sisters, he grew up in the Gavea neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro, a short bike ride from Ipanema Beach, where sparkling waves and sunstruck tourists and G-stringed girls converged. Vava came to surfing at age nine. A goofyfoot with a smooth style and a dashing cutback, he swiftly climbed the Brazilian amateur ranks, a small village of trophies filling his mantel. When Rodrigo Mendes (son of bossa nova giant Sergio Mendes) started hanging out with one of his sisters, the two became pals. They surfed all day, partied all night, and obsessed over surf magazines in between.

If you really look beyond the surface, there’s a whole

realm of perception to be explored.

After the rain puddle, Ehukai Beach Park.

Cut to a few years later. Rodrigo was living in New York, and Vava was enrolled at Rio’s Faculdade da Cidade, studying design. When Vava and his first- ever girlfriend split up he was “lost, bored, and pissed.” He booked a one-way ticket to France, with a brief stopover in New York. His plan was to surf himself into amnesia in the A-frame beachbreaks of Hossegor. He arrived at JFK and subwayed it over to Rodrigo’s Downtown apartment. Rodrigo was in a frenzy. “Swell’s pumping!” he said. “Grab your board, we’re going to Jersey.” It was the last thing Vava expected to find in New York, but he went with it. For the next three days, he scored clean, overhead waves at Sea Girt and surrounding beaches. At night they ran wild in the East Village. Vava was hooked. He canceled his flight to France and stayed—for fifteen years.

Photography is a platform for time travel. I wanted to portray my lifelong experience with surfing through emotional images. Hawaii was a place that could magnify that story, and at the same time provide the elements for new theatrics. All I needed was to live them through a camera and let time do its part.

The surf would never quite deliver the way it did for his arrival, but life certainly did. A resourceful man who speaks four languages and thrives in the presence of beautiful woman, Vava got a job assisting some of New York’s finest photographers. Within a couple years he was shooting his own stuff. Before long, his pictures were appearing in leading fashion magazines worldwide. Vava traveled voraciously, spending time in Paris, London, Los Angeles, Sydney, São Paulo and Amsterdam. In 2000 he won the photo competition at the prestigious Festival of Hyères in France. Around that same time he began the body of work on display here. For the last decade, Vava has been immersed in Hold Your Breath, a book about Hawaii in general and the North Shore in particular. He grew up obsessing over the Hawaii depicted in surf magazines and movies. When he finally arrived there many years later, he found it to be both nothing and exactly like he’d expected.

Kala Alexander, Da Hui’s amabassador.

Enough said.

Joel Tudor is as immortal as it gets. He’s a vortex bender.

He channels past and future more than any surfer in this galaxy.

RIP Dora

jamie brisick: What drew you to photography?

vava ribeiro: As long as I can remember I had a camera in my hand. I always knew that I was going to be doing something visual—an architect, or a designer, or a graphic designer. As a kid I was always doodling and doing little drawings and I was actually pretty good at it. When I got to college there was a photo class that I took and I loved it, and I felt good about it. My brother-in-law was a professional photographer. My grandfather was a photo enthusiast; he always had a camera around. So photography was something that was familiar to me. I started shooting on my surfing travels. But I never set out to be a photographer—it was just a natural extension of my travels. But I really got the first buzz when I was in design school when I started to shoot and develop my film. At that time it was happening at a very subconscious level. I did not know I was going to become a professional photographer, but I got hooked then.

jb: As long as I’ve known you, traveling has been a huge part of your life. When we first met you had separate phone books for London, Paris, New York, Los Angeles, São Paulo, and Hawaii. Where did all your traveling start?

vr: It started in the early ’90s in Brazil. There was a very weird political scenario in the country itself. It was a very instinctive feeling that I wanted something else. I had traveled within Brazil and to Europe as a kid, with my family, and I knew there was something out there for me. I had no real plans for the future, I had a broken heart, I was bored at college, and I was tired of surfing in competition, and surfing itself. So all the main motors of my life weren’t fulfilling me at all. Once I started to travel it opened up this vortex, it opened up these possibilities. For me it was very easy to travel. I’ve always been very adaptable, very easy with new languages. Going to a new country and learning a different reality has always been exciting to me.

The plumeria flower petal does not hold psychedelic properties.

But then again, it smells so nostalgic that it might affect your brain. Forever.

Conan Hayes is the main piece of this whole puzzle. He is the one that introduced me to Hawaii for the first time.

A mystic man himself, Conan is as real and mysterious as the universe I’ve ventured over the

past decades in Hawaii. Hence the image: what appears on the surface is piece of a man bathed in highlight

and surrounded by the unknown. Thanks for the ride, amigo!

jb: Did surfing contribute?

vr: My very first international trip, alone without my family—I was seventeen years old—was a surf trip to Peru. We’re talking around 1988. And I was the youngest guy, I was with four other guys, all older, and we went to all the best places. We went to Punta Hermosa, we went to Machu Picchu, we surfed perfect Chicama. That was probably the gnarliest, craziest trip of my life. It was the first time that I heard about terrorists. There was a terrorist group in Peru. I knew there was going to be big waves, trouble, all the difficulties of traveling in South America. Peru at that time was a fucking shithole. But that didn’t stop me from going. I remember driving through Máncora, and Máncora was a dead town. It was the year after El Niño, there was a mudslide that covered the whole town—all you could see were the roofs of the houses poking out of the mud. It was like a horror/Western movie. You looked to the left and there was this crazy disaster, and you looked to the right and there were these peeling, perfect lefts with no one out, not a soul to be seen. We surfed our heads off. It was this wild contrast of joy and fear. At night they cut the power and we thought the terrorists were going to attack the town because that’s what they used to do: cut the power, attack the town, kill everybody, steal their passports, and move on. The Sendero Luminoso means “The Shining Path.” It was the biggest terrorist group in South America. They were pretty active throughout the ’80s. When the power got cut everybody ran into the desert to hide, and we stayed in our little hut, and it turned out to be just a power shortage. We were shit scared. But that didn’t stop us. We kept on traveling through the desert. I think that planted the seed in me. The sensorial experience; the knowledge that I can function in whatever situation you throw at me—it made me feel special in a way. It made me feel good. Everything after that was easy.

The way that we remember our dreams is never clear.

That’s because most dreams lack sharp sensorial guidance. And without that, they are

just overlapping fragments of memory, embedded into imagination soup.

jb: What would be the highlight of your photography career?

vr: In a professional sense we can talk about the prize I got in Hyères, which was very renowned and opened up a lot of possibilities in my life. It gave me a little bit of status, but it also gave me the self-assurance and confidence that I needed. That was very fulfilling. But highlight of my photography career—that’s a tough question. How do you measure that?

jb: You’ve been photographing the North Shore for over a decade. I remember us talking about how you grew up looking at pictures of Hawaii in the surf mags, and that your photos deal with how you imagined Hawaii to be, and what it actually looked and felt like.

vr: My first trip to Hawaii was in ’99 or ’00, so it’s been twelve years. A lot of the North Shore has changed. A lot in me has changed. Photography is amazing to me because after a while that file, that archive, has a life of its own. When something is about five to ten years old you start to look into the documentary value of it. The more it ages, the more significant it becomes. When I first started to photograph Hawaii the pictures looked like my dreams, or like the images I formulated in my head from reading all the surf magazines. It was like déjà vu. I realized at some point that just like my memories, the actual images I was shooting needed to age, to get some sort of “real” vintage value so they also could speak with that same tone as the images I was paying tribute to. And probably that’s why now these images make more sense then the first time around when I first started to edit the work. Photography is a time travel platform. I wanted to portray my lifelong experience with surfing through emotional images. Hawaii was a place that could magnify that story and at the same time provide the elements for new theatrics. All I needed was to live them through a camera and let time do its part.

jb: Is there a single image from your Hawaii work that you feel captures your impressions of the North Shore?

vr: There’s an image of Jesse (Faen) with the Fish that I really like. He’s lying down in bed with the board next to him, and he’s raising his hand up to block the sun. It’s an introspective moment of a surfer. It has a vague narrative to it. It could have been me in that image. It could have resembled something that I saw in a surfing magazine when I was a kid. But it also resonates to the time that I was there hanging out with Jesse. There’s another picture where Joel Tudor is looking at me, and he’s wearing a t-shirt that says “Dora Lives.” That image could have been shot in the ’70s or the ’80s. When I shot that image then he was paying reference to something that I saw as a kid, of a place I only knew about through the magazines. Now I look at that image and think about first: the moment when I took the shot, and second: the period where I was a kid growing up with surf mags that featured the North Shore. There are two layers to it.

jb: Who are your favorite photographers?

vr: I can decipher my photography influences by layers. The portraiture of Richard Avedon, the colors of Stephen Shore, the haunting portraits of Emmet Gowin, the raw youth from Larry Clark, the skin and innocence on Jock Sturges, the cold and abstract compositions from Michael Schmidt. I’ve always been a photo junkie. I could name 100 photographers on that list. I also like movies. Strong visual narratives: Kurosawa, Kubrick, Antonioni, Lynch …

jb: What makes a great image?

vr: There’s no rationale to it. There’s no mathematical formula. There’s a distinct sense you get when you look at a good image. That’s the beauty of photography for me. It has to be felt. It’s not something that you see; it’s definitely something that you feel. It’s one of the most sensorial mediums that you could possibly have. The only thing I could possibly compare to it is music. You listen to it and you have a rush of thoughts and emotions and feelings. Photography does that to you. In a funny way, a good photograph will start a dialogue with you—internally you have this conversation going back and forth with the photograph. That to me is a buzz. That to me is what makes it so amazing. And another thing: photography as a medium is close to magic. A camera is an amazing, magical instrument. You’re recording a fraction of a second of a moment, and it stays. And you’re living that moment. And that moment is a whole different feeling when it’s frozen. This little machine does all that. What else do we have out there that is such a clever trick?

jb: What are you most inspired by right now?

vr: Music has always been important. I look at other people’s photography and painting. I try to draw inspiration everywhere. I could listen to rock or electronic or jazz and images come to my mind. If I close my eyes in darkness and listen to music my head creates images. Imagination is the most important thing in my head. Creativity has a process and formula. Imagination doesn’t. Dreams are formulated from pure imagination, you can’t control or replicate that process, but if you manage to get people close to it in what you do, then you’ve got something. That’s art to me. ■