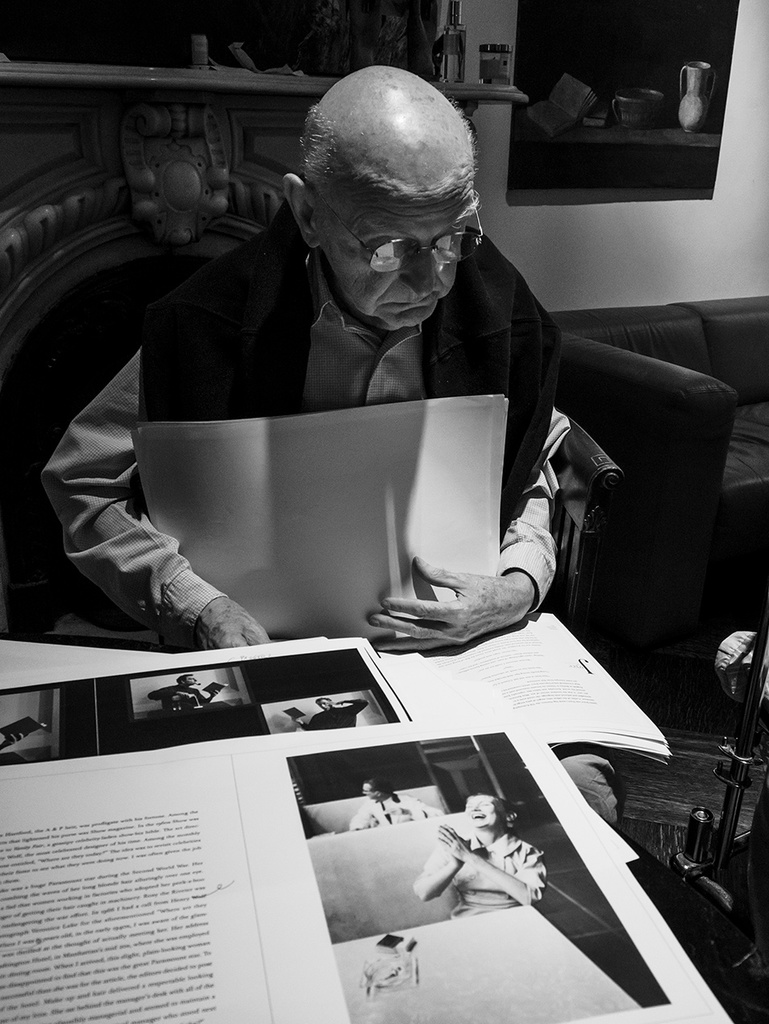

Guided by intuition and drawn to the complexities of being and time, Duane Michals has mastered the art of taking portraits that dive into the introspective space behind the image. His work stares into the void that lies between the seen and the unseeable. In order to bridge this gap, Michals has developed a signature style of writing over his photos, a gesture which gives a narrative dimension to what he calls his “prose portraits.” Shortly after Michals underwent a medical procedure, Panos Galanopolous visited him to rehash memories through his portfolio. At the age of 86, he is currently in the process of finishing two books, which he plans to be his final projects.

panos galanopoulos: I’ve known you since I was eighteen, and I’m 34 now. You’ve been a huge impact in my life in so many different ways. You got me my first job in New York City with the New York Times Magazine. Colin, who’s the editor-in-chief of this magazine, and I studied your images growing up. You’re such a master at what you do, and I’ve listened to you speak a million times, and it’s so moving and so special. I know you started later on in your life, so I wanted to hear a little bit about how you started.

duane michals: I was never an amateur. When I was in high school, I didn’t belong to a photo club. I never took pictures. I didn’t even own a camera. I took a little course at Parsons, but it wasn’t anything. I took pictures in the army, which became my army book eventually, but I had an aesthetic itch. I knew I wanted to do something in the arts—I was interested in writing, I was interested in photography, I was interested painting—but I never thought of myself as a photographer. Then when I was 26, I went to Russia. I was working at Time Inc., and I borrowed a camera. I’ve been very good at recognizing a moment and grabbing it, mostly when I don’t know what I’m doing. My great saving grace was just recognizing the moment and jumping in without a parachute. So that’s how I got involved with going to Russia with a borrowed camera, and it took me about a year or so. I had a party, and somebody brought a guy named Danny, and he was bored at the party, and my photographs were like the Dead Sea Scrolls. He was sitting unwinding my photographs, and he said he’d go ahead and give me a key to his studio. He started letting me use it on the weekends. So that’s how the whole thing got started. I’d be out taking portraits of my friends, just for fun every Saturday.

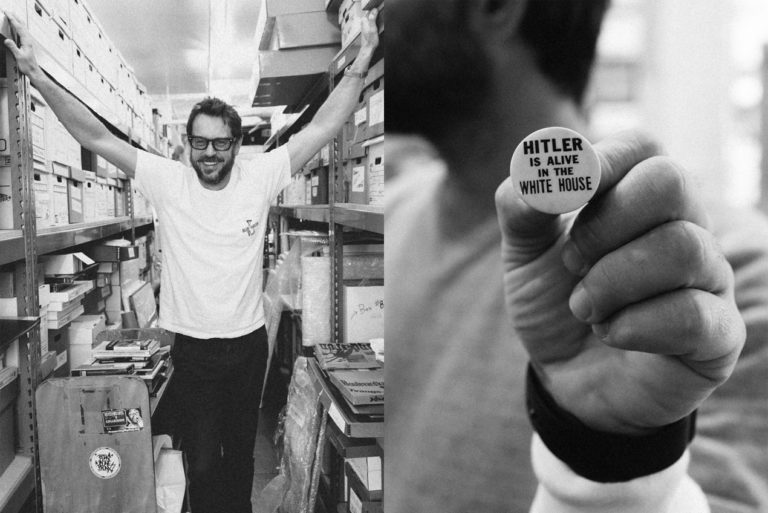

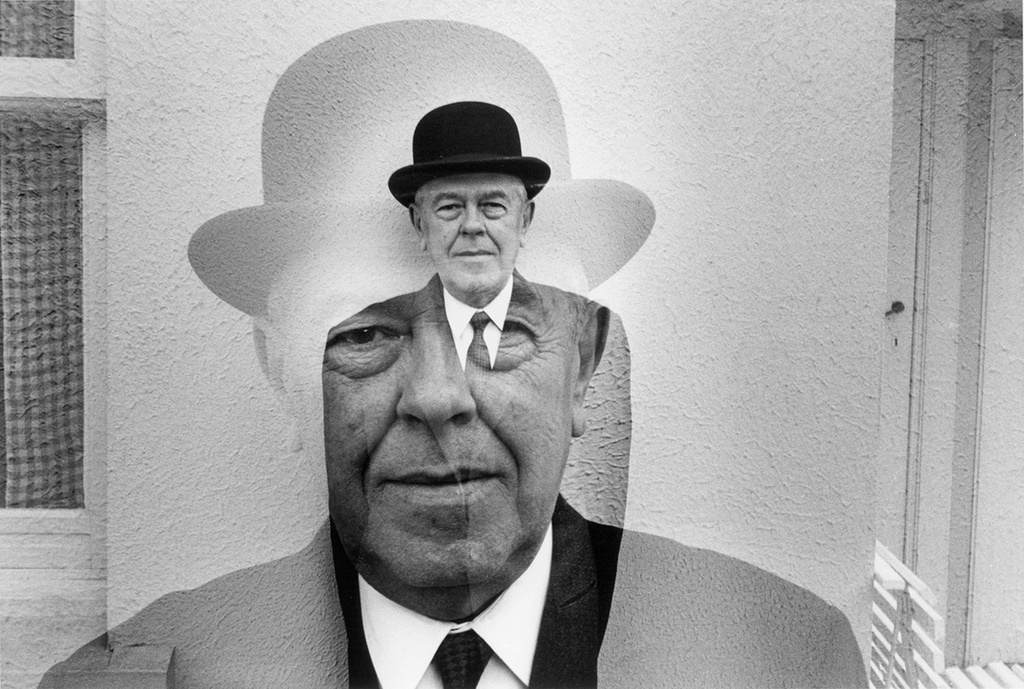

René Magritte double exposure

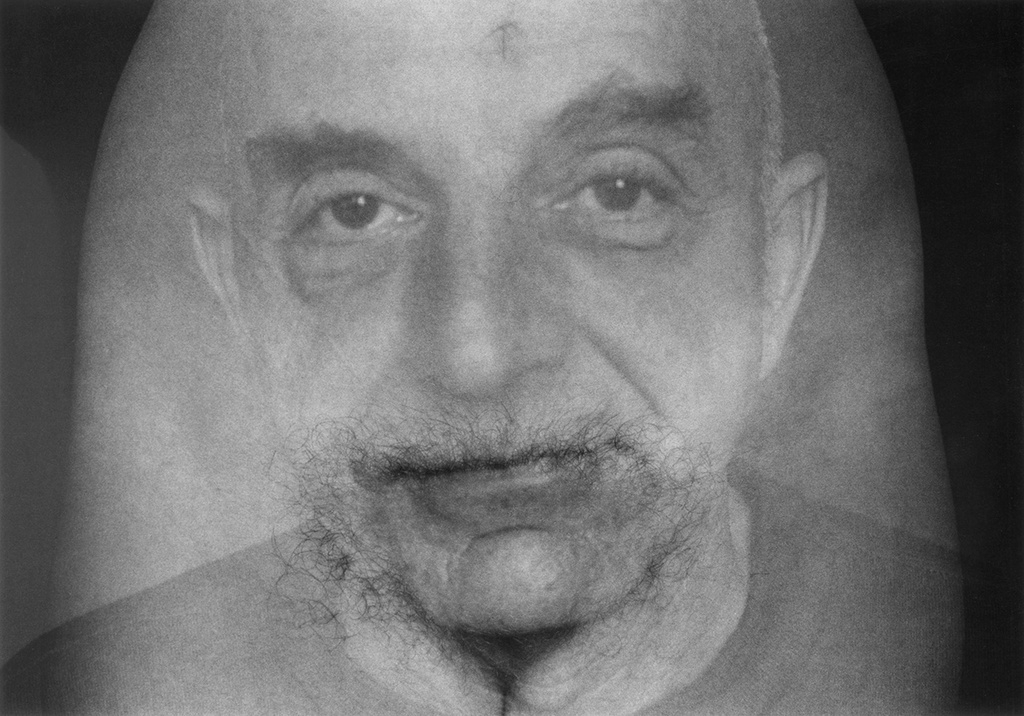

Self-portrait with feminine beard

pg: So that was one of those pivotal moments that led you to photography.

dm: There were others too, but it was simply that. It was recognizing that I had an opportunity. “Seize the moment.”

pg: Carpe diem.

dm: I’ve always done that. I thrive on doing things that I’ve never done before. Most people thrive on what they feel is comfortable. I’ve always liked doing things I’ve never done. I just finished this book. Well, I’m doing two books: one is a coffee table book with Phaidon and the second is with Monacelli Press, which is a part of Random House. I get very bored with most photography books, because it’s picture, picture, picture, picture. One of my guiding things is I like surprises. I like that sense of serendipity. So I did a book called ABCDuane, and for example, under “S” I wrote my favorite Shakespeare poem. But then what I did with it was I described how I imagined it to be when he wrote the poem. He’s sitting in his house in Stratford on the second floor, and it’s December and there’s a little smoke from the fireplace and the light is very soft, and he looks out the window and he can the roofs on the houses. He’s looking for a special word and he’s trying to finish this poem, and then it comes to him. He has a little piece of parchment and he’s writing on the parchment with a quill pen. He just sits there for a minute until he finds the word, and then I printed the poem. I’m also doing an exhibit called The Storyteller.

pg: And you have a lot of stories.

dm: I was with Truman Capote the day Bobby Kennedy died. I photographed him a number of times, and we had a nice working friendship. I wasn’t working my way up through the ranks, so we could talk. He told me about the last time he saw Bobby Kennedy. Truman had gone out to get a Sunday Times and saw Bobby standing on the corner talking to a group of young teenagers. Kennedy spotted Truman and yelled, “Truman, come over here. I want you to talk to these boys.” They had been smoking, and Bobby was admonishing them about the evils of nicotine. Kennedy continued, “Mr. Truman, he would never smoke cigarettes.” And Truman replied, “Heavens no, I would never put a fag in my mouth.”

pg: The first photograph you ever took, do you remember it? Was there a first photograph that really impacted you, where you were like, “Holy shit, this is amazing. This is what I’m going to do?”

dm: When I went to Parsons, I took photography for a semester, and it was a total waste of time. I dropped out. But I went to Stillman’s Gym and photographed a lot of boxers. I think those were it. With the photographs from Stillman’s Gym I thought, “Wow, these are good.”

pg: This is interesting for me, because I went to school for graphic design and became a creative director and I love photography. It was my first love. I know that your first jobs in New York were in magazines with graphic design. What magazines did you work for?

dm: My first job was with Dance Magazine. I dropped out of Parsons and I knew there was a good designer at Dance Magazine. So I went there and I was interviewed by the guy whose job I wanted. I came back to my room with all these stupid dance layouts and I thought, “Now what am I going to do?” This was during the Korean War, and the next day the guy was drafted, so I got the job.

I’ve been very good at recognizing a moment and grabbing it, mostly when I don’t know what I’m doing.

pg: No way.

dm: It was $50 a week and my apartment was $50 a month, so it worked out. I was there for a year, and then I had a friend who was a copywriter for Time Inc., and he knew an opening in the promotions department. I went there and was there for two years and found out you could go to Russia, and so I went to Russia.

pg: That’s a pivotal moment.

dm: All of these were just about grabbing the moments.

pg: Your work is more than just capturing a moment. There are more narratives, structured photographs that embody a narrative progression. How did this evolve?

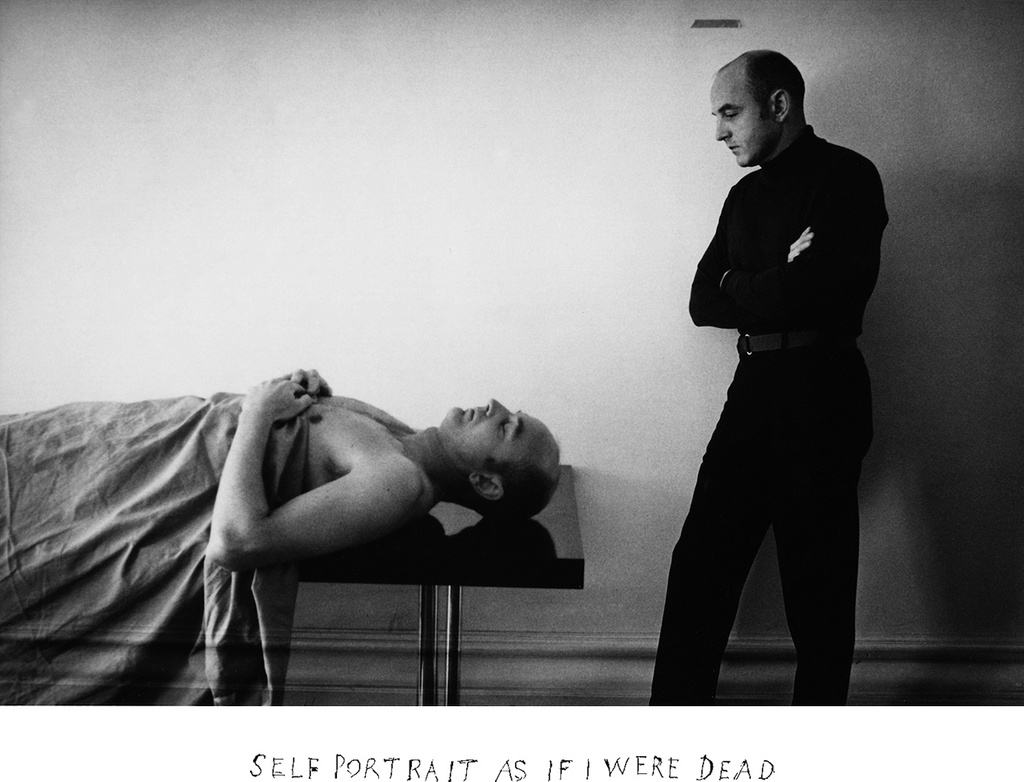

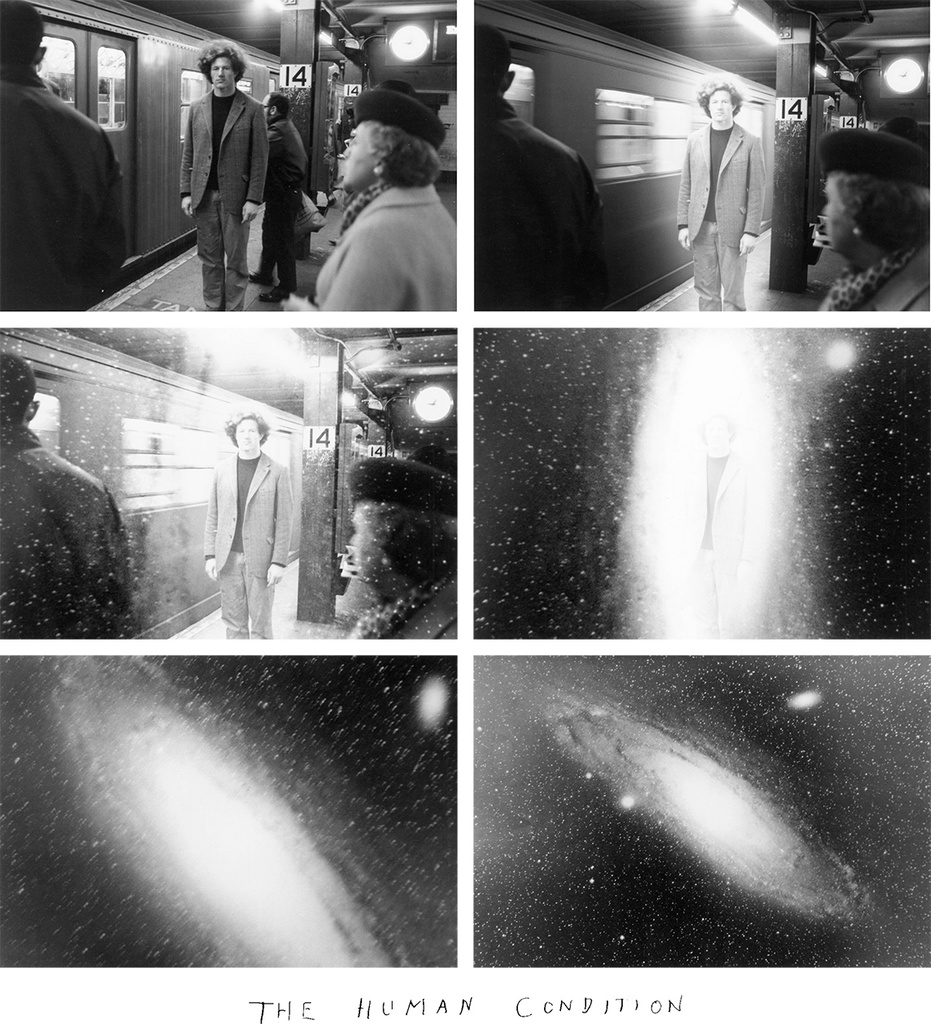

dm: It came out of my frustration with the nature of the beast. The classic example is that I can show you a picture of my mother, my father, and my brother standing next to each other smiling, but there was no relationship. They hadn’t screwed in 40 years and they didn’t even like each other. I had to figure out a way to get behind the picture. What I mean by that is, the photograph shows you exactly what someone’s nose looks like when they’re 27, it’s the exact clothes they were wearing, but I think it’s when the photographer annotates and brings insight into the photograph that he becomes the artist. Up until then, it’s just description. There’s a new thing I’ve done and I’ll call it “prose portraits.” I did sequences, because I was so frustrated with the decisive moment. I could talk about the spirit leaving the body more eloquently in a little six-picture vignette. All of this came from frustration with the decisive moment, and my frustration with the inability of the camera to go beyond description. I had to figure out how to do that. That’s what this book is about, too. I think this is a new kind of photo book.

pg: It couldn’t have happened without your life. That’s an obvious thing to say, but your life works perfectly with this book. You’ve really combined your work with other people’s work with your inspiration. You’ve unified it, and it’s really incredible. Even the older work seems new still.

dm: It’s still valid.

pg: Even more valid than ever.

dm: It makes a lot more sense, because you can see the early work, and now you can see the later work and how it all came together. The early work is still valid, and when I talked about Joseph Cornell, I described what it was like being with him, and how he responded, which extends the photographic experience.

pg: Do you consider photography art?

dm: Some, but not all photography. There are photographs that transcend mere photography and become art. I think so much of Cartier Bresson’s work, and Robert Frank’s. They’re kind of elegant, and they don’t work at all alike, but the elegance of their vision is there. And then I just like Garry Winogrand. He was just a snap-shooter, but there are some photographs that truly are art. The photograph has to evoke a response in you. If it’s just another picture of a guy walking down the street, then so what? But when it has that thing that touches, it stirs something in you. You know it’s just a guy standing there, but somehow you respond.

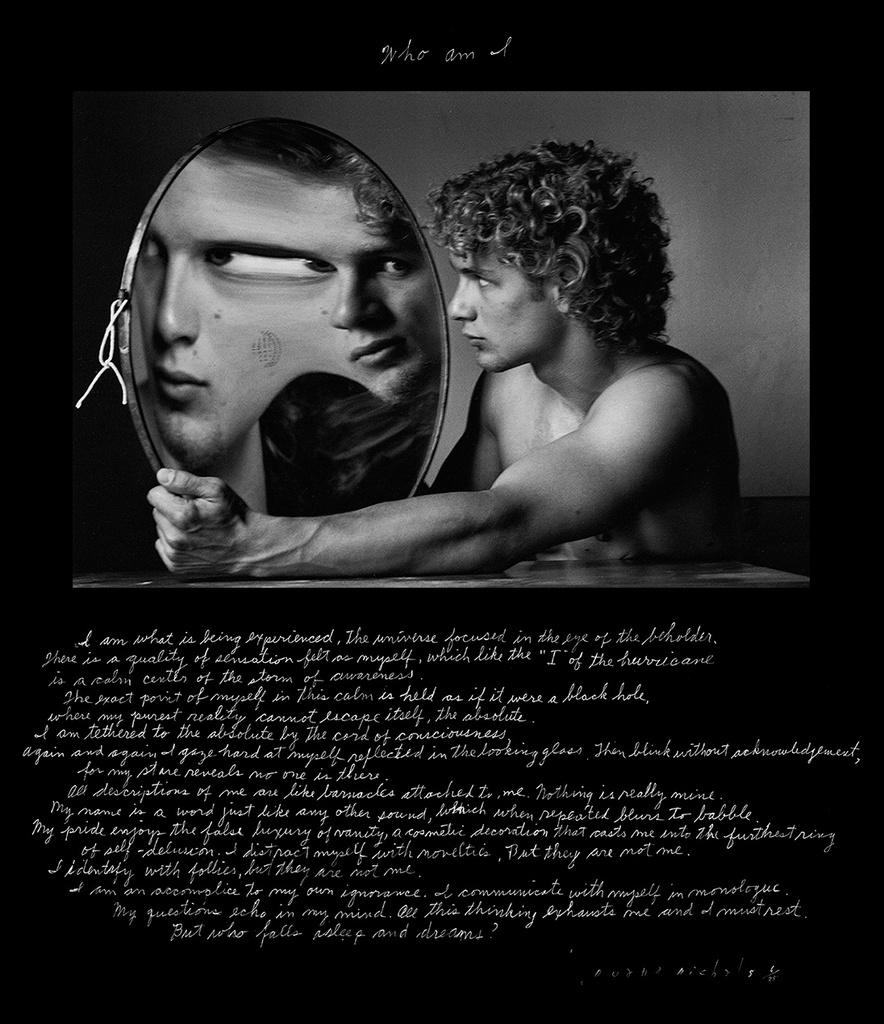

pg: You have this really beautiful piece titled Who Am I?, which is one of my favorite pieces that you’ve done. Where did that come from, and can you tell me about that piece?

dm: Well, it’s a sensual question. It’s all from the curiosity. It’s not a curiosity to see what places look like, or what people look like. It’s a curiosity of the nature of what it means to be human. To get to the very source of, “What is this?” Literally, “What is this?” I think most photographers say, “What is that?” But they never say, “What is this?” So my work was always interior, very introspective.

pg: I know life is an extremely special thing to you. What were some of the joys of your life?

DM: Fred. Fred’s been my joy. And now it’s become more intense. I’ve fallen in love with him all over again. In here, I have a section called “Fred Says,” and there are quotes.

pg: You took a couple photographs of René Magritte, which are incredible. I know he was an influence on you. What was it like photographing him?

dm: First of all, here’s the thing about influences: a good influence liberates you and a bad influence traps you into the style of whoever influenced you. If you end up being a little Cindy Sherman, doing self-portraits, that’s a bad influence. A good influence is what I would call a point of departure. You look at the work and you recognize what it stirs. I always found Magritte amazing. I had no question about it. Every time I saw one of his pieces, I thought, “Where did this come from?” That first Magritte I saw was at Harper’s Bazaar in the early ‘60s. I thought it was a photograph, but it was a painting. There was a nude woman holding a big mirror, and in the mirror it was her. That was my first introduction to him. It was that stirring moment. He never ceased to please me. Going to visit him was even beyond belief, actually sitting down and having lunch with him.

pg: Were you nervous?

dm: Yeah, sure. He was so generous and let me have the run of the house, photographing whatever. That was major. I knew this woman who was coming back from London, and she knew someone who was writing a book about him. I thought, “I’m not going to write him a love letter, but I’ll take pictures. That’s what I do.” And lo and behold, it was okay. Another moment, like going to Russia, which opened everything.

pg: Russia was really important it seems.

dm: Without Russia there would be no career.

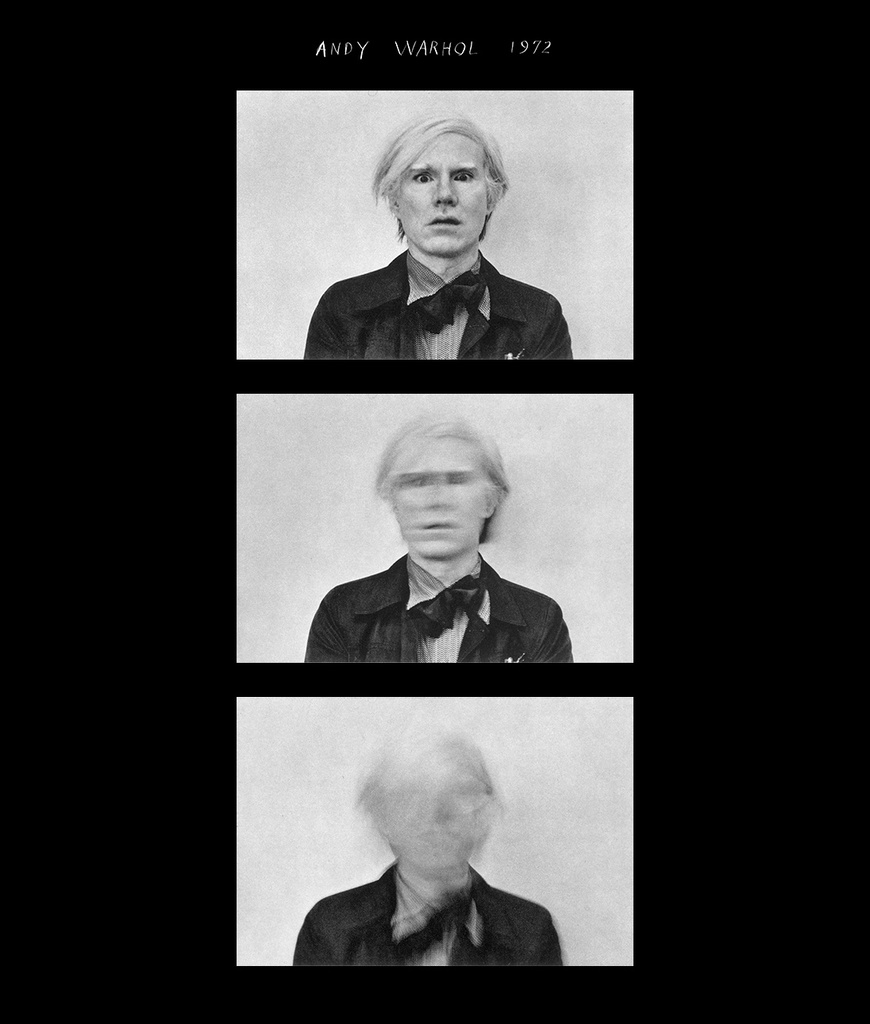

pg: You grew up in the same town as Warhol?

dm: He was born in McKeesport Port, but they got uppity and moved to Pittsburgh.

pg: Did you know him at all?

dm: Not really. I met him in New York. I had a friend who was a layout artist for a very high-end women’s department store. Andy was doing ads for them, and he found out that I was from McKeesport, so we were a natural match.

pg: You took some great photos of him and his mother, which were very special. I’ve never seen Andy shot looking as happy as he was in those photos.

dm: They were very, very tight. With all of his fame and notoriety, he would come home every Saturday night strait from a nightclub and be at church every Sunday morning with his mother. The contradiction of the hippest of all the hipsters is going to church with your mother and living with your mother. It was kind of curious.

pg: I remember the photos of when you went back to your own home and you double exposed old photos of your family onto the rooms as they are now.

dm: I didn’t include any of that in this book, which I should have because that’s a whole interesting relationship in itself.

pg: I remember when you shot it, you showed me, and it was very emotional.

dm: Yeah, and it still is. That particular series made an imprint on people, because everyone has someplace that they came from. We have all these mixed up feelings about what actually happened.

pg: Any other pivotal moments in your life that you want to talk about?

dm: This last year for me has been huge. I entered my 80s.

pg: Do have any daily rituals?

dm: None, other than masturbation.

pg: Any artists now that inspire you today?

dm: Yeah, there is one. It’s a guy in Pittsburgh. His name is Robert Qualters. He’s about my age. He was born in McKckeesport and then he moved to Clairton, which is not an upgrade. He left Pittsburgh and went to study in California for three years. Then he came back to New York and taught art someplace and then went back to Pittsburgh and found what he should be doing. I think he’s terrific. He’s been painting there for 50 years, and I think the work is very valid. There’s two worlds. There’s the world of art, and then there’s the art world. The art world is Sotheby’s, Larry Gagosian, $70 million Warhols, the show business of the New York art world. And then there’s the world of art, and those are the people like this guy, who’s been painting in Pittsburgh all of these years and evolving in his own way. He won’t ever become famous, he’s never going to be a New York star, but he’s the real thing.

pg: Where do you draw inspiration?

dm: Inspiration is very important. If I find something exciting or strange, it sort of gets into my head. I sort of think about it, and there might be a moment where I suddenly figure, “Of course.” I trust my instincts completely. I take inspiration from absolutely everything, and I like to read. I like poetry.

Andy Warhol would come home every Saturday night straight from a nightclub and be at church every Sunday morning with his mother. The contradiction of the hippest of all the hipsters is going to church and living with your mother.

pg: What’s a photograph that you really love that you’ve done?

dm: I really love all of them, and all of them have a private meaning for me because I knew all the ingredients that when into taking the photograph. I like the Joseph Cornell photograph. I like the double-exposed nudes. I like the Russian picture.

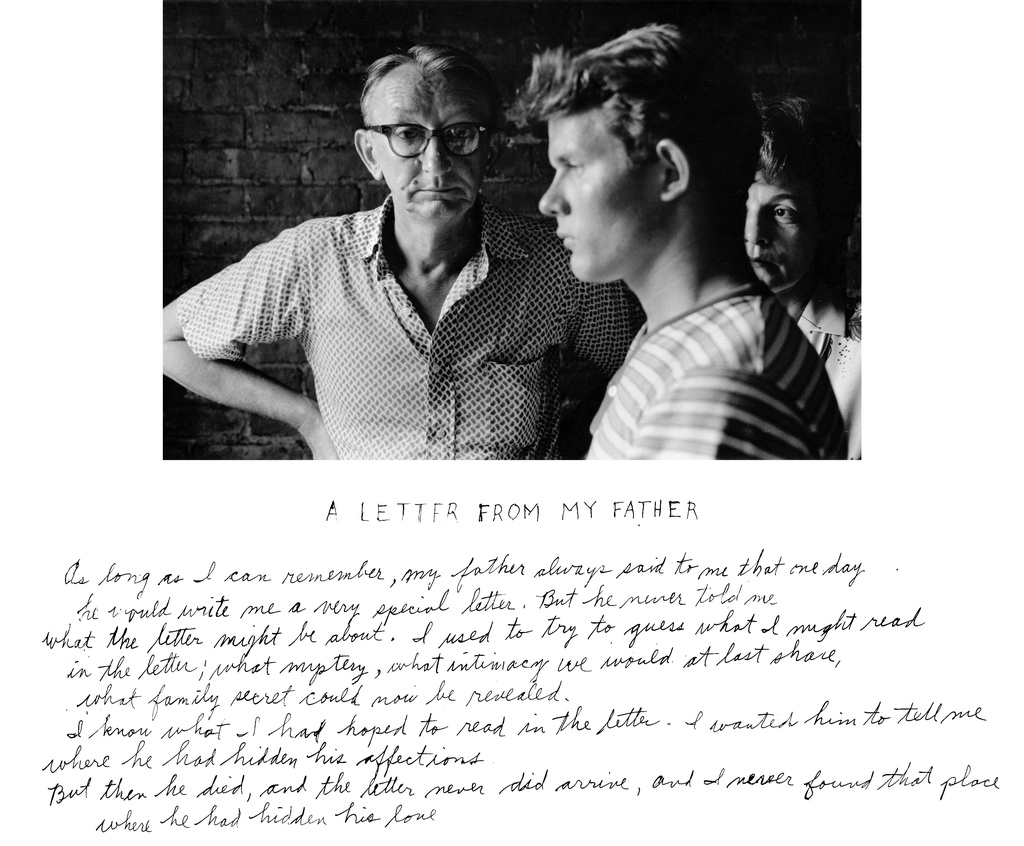

pg: There’s a picture of your brother and your father that I know you like a lot.

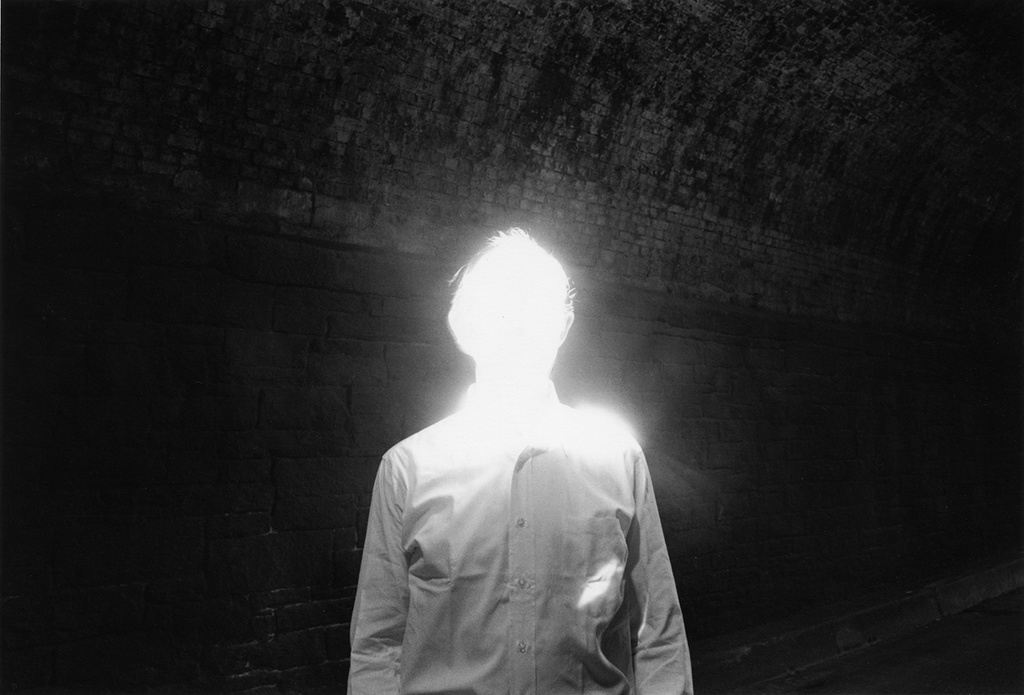

dm: I wrote a letter about my father when he father died. That’s the first thing I wrote, and the dam just broke. I ran into a teacher from an art school and he said, “The kids at school are saying that your work is so bad that you have to describe it underneath the picture. What should I tell them?” I said, “Tell them that in five years they’re all going to be writing on their photographs.” I get a great deal of pleasure, as you can imagine, but it’s a private pleasure. Most portraits are what I call “stand and stare,” which everybody does. You stand and look in the camera. Then in another type of portrait, which I call “prose portrait,” rather than showing what somebody looks like, you try to give the atmosphere of who the person is. The idea is that you don’t necessarily show somebody.

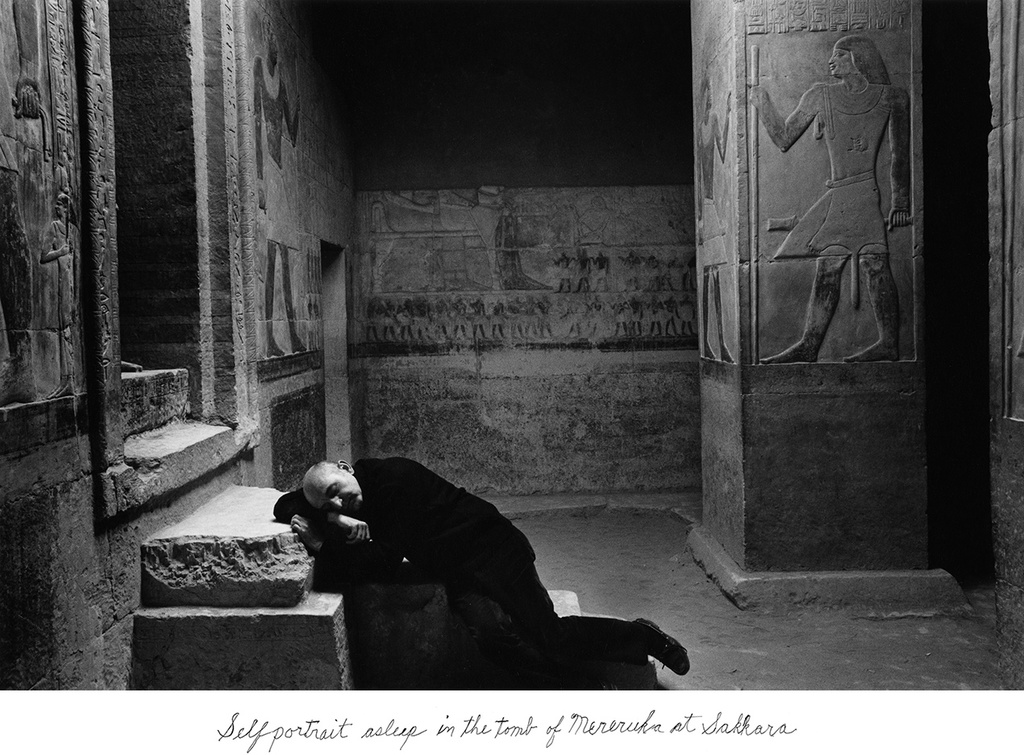

Duane at his townhouse, July 2014.

pg: Where are you going after this life?

dm: You mean, when I die?

pg: Yeah, if you die, if that’s what it is.

dm: I don’t know. I’m of two minds. There’s the logical mind that says the body stops pumping blood and you’re dead. Boom. That’s what it looks like. And then there’s another mind, which is an Eastern mind, and that mind has experienced really deep consciousness. We’re all swimming on the river of the surface of consciousness, and that mind says that the energy is regurgitated. Duane Michals doesn’t exist anymore, you can forget that one, but the energy that was Duane Michals under the fictitious label of Duane Michals is reconstituted. That energy continues, but forgot about Duane continuing. This is an illusion. We were in a restaurant today, and there was a lady who had a baby, and we were commenting on how that little kid will end up being. I was a baby once, and there is this constant self that goes through all of the evolutions and generations of age. It’s so interesting to me that, through adolescence and middle age, there is a constant self.■